c. 1876 || Students threaten janitor with lynching

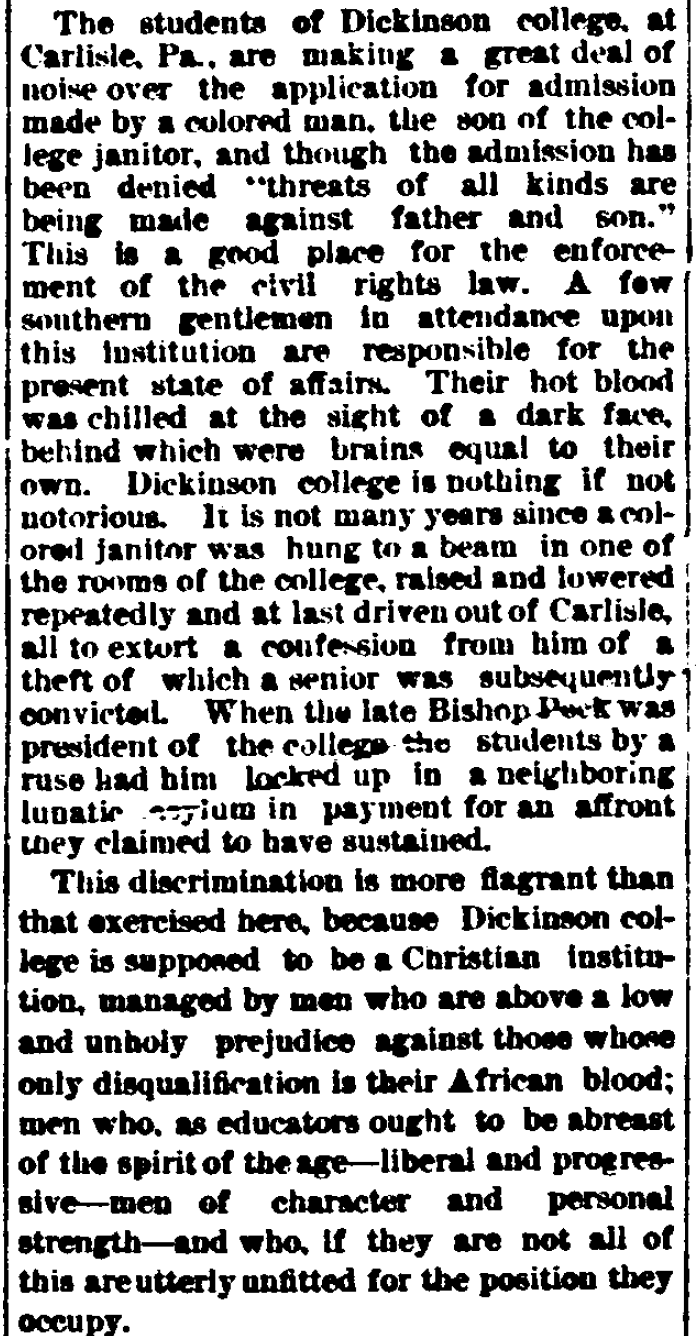

During the middle of the 1880s, Dickinson College made national news because it was contemplating for the first time the racial integration of the school. There were sharp opinions expressed on both sides, but one pro-civil rights newspaper from Ohio made a startling claim in the course of addressing that debate. “Dickinson College is nothing if not notorious,” the newspaper wrote. “It is not many years since a colored janitor was hung to a beam in one of the rooms of the college, raised and lowered repeatedly and at last driven out of Carlisle, all to extort a confession from him of a theft of which a senior was subsequently convicted.” There is no record of this terrifying story anywhere in the college archives. We have searched diligently, but so far have been unable to find any other corroboration in newspapers, letters, diaries or other available records. It’s possible that it never happened. Nineteenth-century newspapers were notorious for spreading what we would call today “fake news.” But it’s also possible that this shameful episode did happen and has simply been erased from the college’s history. There is one potential explanation, however, that might fit with the details of the alleged case. Sam Watts and his brother Henry (known as “Judge Watts”) both worked for years at Dickinson as janitors and waiters. Older brother Henry finally retired during the late 1860s or early 1870s, but the younger sibling Sam was actually fired (or perhaps quit) for an unknown reason in late 1876. Could he have been terminated (or have fled) because of this false accusation of theft and then the threatened lynching episode? If so, the consequences became even more tragic for him not long afterward.

In the spring of 1877, Sam Watts was badly burned at a factory in Harrisburg while reportedly looking for work. According to newspaper accounts at the time, he was unemployed, but also presumably homeless or perhaps suffering from some other challenge (like addiction) because he somehow fell asleep at the factory, which was why he later got injured. One reason for suspecting underlying problems comes from later records. Watts had been married to a woman named Martha (who was a washerwoman in Carlisle) and they had four young children. However, later U.S. census records indicate that Martha divorced Sam at some point during this period, and that by 1880, Sam was disabled and living alone in the Carlisle poor house. We have uncovered no final records yet regarding the cause of his death. The Class of 1870 did recall Sam Watts (and his brother) fondly in their recollected accounts of the “Corps of Hygiene” compiled for their 35th reunion in 1905, but they made no mention of any of these tragedies (which would have occurred after they had graduated). Yet given the evidence and suspicious circumstances, we cannot help but wonder if it was Sam Watts who was threatened with lynching by a band of angry and mean-spirited Dickinson students sometime around the school term of 1876, and if it was that episode that sent his life into a downward spiral.

Sources: Springfield (OH) Sunday Globe-Republic (quoting Cincinnati Times-Star), “Barbarism in American Institutions of Learning,” October 31, 1886 (Newspapers.com); Harrisburg Patriot, “Severely Burned,” May 12, 1877; US Census, 1880, Carlisle (Ancestry.com); “Corps of Hygiene,” Class of 1870, 35th reunion, Microcosm, 1905 (Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections)

1877 || Ex-slave and janitor George Norris dies

On Monday, June 11, 1877, the minutes for the Dickinson College faculty meeting contained an interesting notation: “The death of Geo. Norris for eight years Janitor in charge of the Bell was announced. Born a slave, a servant in the confederate army during the early part of the war, he was one of a class rapidly disappearing & a fitting representative.” Just a few days later, the Carlisle Herald reported that Norris had died from consumption and that his funeral was attended by many of the students. He was clearly an important figure in both the college and town. By September, newspapers in nearby Harrisburg were even commenting that “no less than twenty-five colored applicants” had materialized “to fill the vacancy” (which eventually went to his son, George, Jr.). Years later, a recollection put together by the Class of 1870 called Norris, Sr. “an especial favorite” of their group. Yet beneath all of the dignified expressions of remembrance for this supposedly beloved janitor, there were also some disturbing signs of what Norris’s life must have really been like. Students recalled him as a kind of physical freak, “very tall, ungainly and loose-jointed,” who “possessed the rather unusual ability of placing his hands upon his kneecaps when standing upright.” They noted almost cruelly that “when a slave his master was accustomed to call him to the house to furnish amusement to his guests.” The grown men from the Class of 1870 were certainly not above remembering fondly how they once mocked Norris. They recalled how they gave him a new watch at a special college ceremony, only to laugh uproariously as he delivered a solemn-sounding oration of gratitude written for him in a mishmash of slang and phony Latin by a witty classmate. According to the faculty minutes, Norris had been enslaved by the Confederate army during the early part of the Civil War before perhaps escaping behind Union lines. Yet exactly how he got to Carlisle and onto the staff at Dickinson by the late 1860s remains unknown. More important, what also remains almost unknowable were Norris’s true feelings about the young students who claimed to love him, but also somehow managed to use him for “amusement” just as his master had done during the era of slavery.

Sources: Faculty minutes, June 11, 1877, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections; Carlisle Weekly Herald, June 14, 1877; Harrisburg Telegraph, “From Carlisle,” September 1, 1877; “Corps of Hygiene,” Class of 1870, 35th Reunion, Microcosm, 1905.

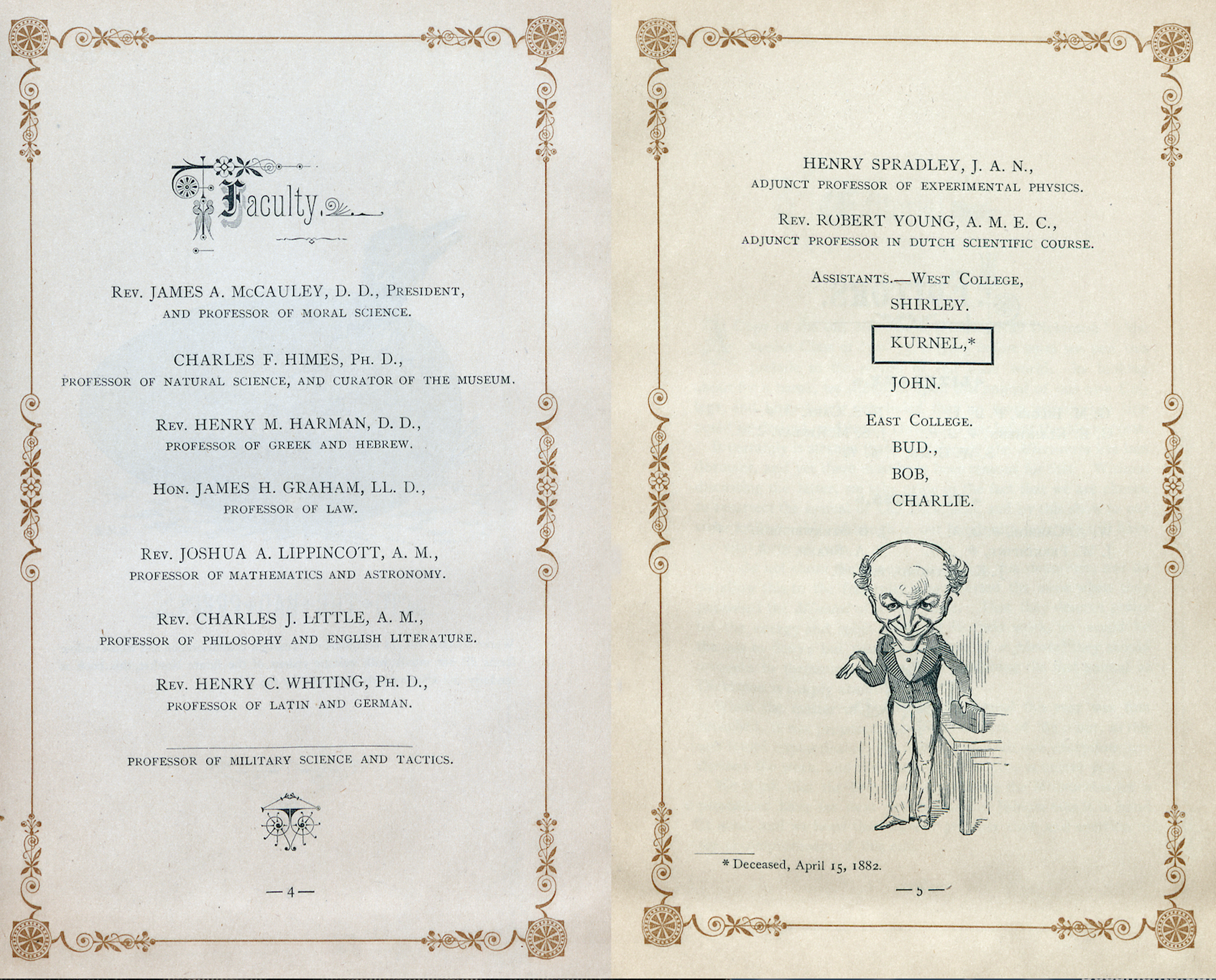

1882 || Students poke fun at college janitors

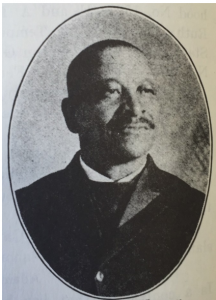

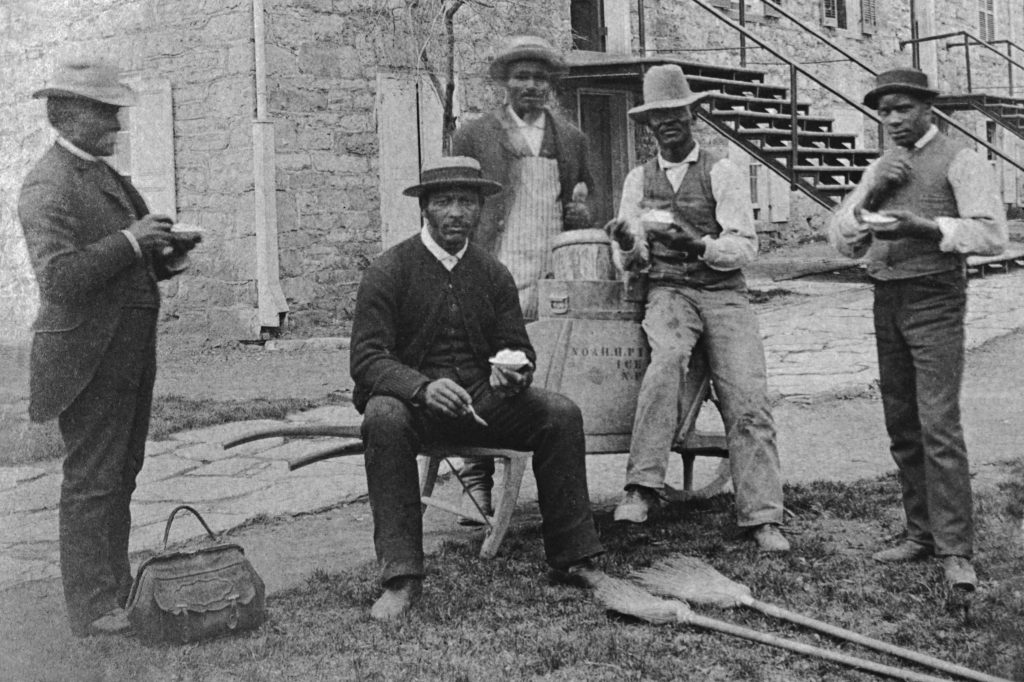

According to rules established by the college in 1830, janitors at Dickinson were required to ring the college bells, start and put out fires in classrooms and the chapel during winter months, attend faculty meetings to help summon wayward students, provide food services, and to employ additional labor whenever needed to help maintain the college buildings and grounds. Janitors were also considered partially responsible for protecting the security of the campus, and especially for keeping away unwanted vendors. Their job was important and critical to the success of the college. Moreover, to sustain this perpetual workload, nineteenth-century college janitors routinely lived on the Dickinson campus in the same buildings as the students. Many of their wives assisted with washing, boarding and other domestic chores for the young men. Their children played on the college grounds, and sometimes worked for hire themselves. The janitors and their families thus interacted with most Dickinson students on a near daily basis. No rule dictated that the college janitors had to be black men, but during the nineteenth century, it appears that all of them were black, and most were former slaves and Union army veterans. The resulting mixed race community showed plenty of signs of mutual affection, occasional friction, some evidence of juvenile pranks, and more than a few examples of shocking color prejudice. One might find all of those traits embodied in a handful of cartoons that appeared in student publications during the 1880s, such as the 1882 yearbook, the Microcosm, which featured a page dedicated to the head janitors at the time (Henry W. Spradley, West College and Robert C. Young, East College), along with some of their children and family members (Shirley, John, Bud, Bob, etc.) and pets (Colonel, a.k.a. “Kurnel”) in a parody page situated just opposite the main faculty listings. The yearbook editors decided to give the janitors some phony academic-sounding titles (Adjunct Professor of Experimental Physics, etc.), presumably as a way to mock the pretensions of a staff that the young men sometimes found overbearing.

1885 || College janitor hosts seniors for dinner

In November 1885, Henry Spradley and his wife Mina hosted the senior class of Dickinson for dinner in the South College building (no longer standing) where the Spradley family resided. Spradley was a former escaped slave and Union army veteran who was then in his sixth year as the janitor and bell ringer of West College (now “Old West”). The event was unprecedented and made the local news. “The class felt especially delighted upon the occasion,” reported the Carlisle Sentinel, “as it was the first time in the history of the college –the first time in over a hundred years– that a class had been so honored.” Called to order after chapel by fellow janitor Robert Young, the seniors marched in unison over to Spradley’s buffet set up at the South College dining hall. The reporter observed that the boys were “proud of each other” for being so “beloved” by their gracious host. “No more delicious turkey was ever eaten, nor more fragrant coffee ever drank,” claimed the newspaper. The warm-hearted evening ended with toasts to Spradley and the other janitors, and even some original songs, included one that apparently went, “Here’s to Mr. Spradley / Who never does things badly.”

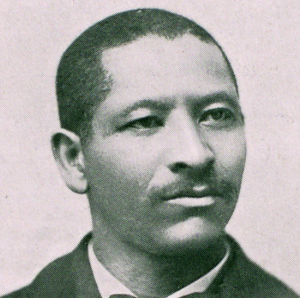

1886 || Robert Young tries to integrate Dickinson

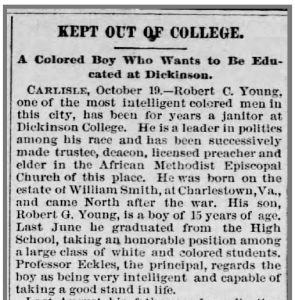

Robert C. Young was an imposing guy, “great, stout” and “broad-shouldered,” according to the students at Dickinson. He had been born enslaved in western Virginia around 1845. Then somehow, after the Civil War, still as a teenager, he found his way to Carlisle and got hired as a household servant to the president of Dickinson College, Robert Dashiell. Young made quite an impression at the college, “known to turn upon his tormentors with great vigor” whenever mischievous students tried pelting him with snowballs or other “convenient missiles.” Before long, Young became the senior janitor at East College and raised a large family in Carlisle with his wife Matilda. By the middle of the 1880s, Young and fellow janitor Henry Spradley seemed secure in their place on campus. But then the indomitable will of Robert Young set off an institutional crisis. His eldest son, Robert G. Young, graduated from high school in Carlisle in 1885 and his father decided that he deserved an opportunity to get a college education. The school had never before had any student of color, but it was an era of change. Dickinson had just admitted its first female students or “co-eds.” There was an Indian school now thriving in Carlisle. And, of course, the Constitution had been remade after the Civil War with the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments, all promising freedom and equality regardless of color. Yet most colleges and universities in America remained segregated. But Young believed it was time for change at Dickinson as well and pressed hard for equal consideration. He wanted his son admitted to the Dickinson preparatory school, which was then a standard transitional experience for many students who were planning ultimately to graduate from the college. Nothing happened at first. School officials seemed determined to ignore this violation of their social norms. But Young persisted on behalf of his son and the stand-off soon made national

news. “KEPT OUT OF COLLEGE,” reported the Philadelphia Times in October 1886, “A Colored Boy Who Wants to Be Educated at Dickinson.” The Philadelphia North American was merciless in its criticism. “The southern young bloods who have been airing race prejudice at Dickinson College are evidently beginning to feel their inferiority to the negro.” The story earned coverage in Georgia, Ohio, Massachusetts, New York, North Dakota and elsewhere. The Springfield Ohio Globe-Republican dismissed the resistance of college officials as blatant prejudice, blasting the “barbarism” of American schools like Dickinson that reportedly had once even allowed their students in Carlisle to prepare to lynch a black janitor falsely accused of theft. All of this attention put Dickinson officials on the defensive. They denied any interest in segregation, but claimed (weakly) that the Youngs had simply failed to make a proper application. One unnamed professor later wrote a letter to a Boston newspaper claiming the whole affair was being over-hyped. “There has been some opposition on the part of some of the boys,” he wrote, “but a large number have kept agitating the matter in the boy’s favor, and it is from these that all these newspaper squibs originate.” Eventually, the Dickinson prep school admitted Robert G. Young, but he only seems to have lasted on campus for about a year. Why he left remains uncertain. The records don’t exist, and the newspaper coverage died down. However, in 1940, while he was widowed and living with his daughter Mary in Newton, Massachusetts, 69-year-old Robert G. Young, was still proudly listing his educational experience as one year of college. The first actual black graduate of Dickinson (John Robert Paul Brock) would not receive his diploma until 1901. Esther Popel, the first female black Dickinsonian, graduated in 1919. Fortunately, father Robert C. Young lived long enough to see all of that. He died in 1922, after becoming the longest serving employee in the history of Dickinson College, having worked for nearly four decades as domestic servant, college janitor, and eventually as the main campus policeman.

Sources: Philadelphia Times, October 20, 1886; Harrisburg Patriot, October 21, 1886; Macon (GA) Telegraph, October 26, 1886; Philadelphia North American, October 26, 1886; Carlisle Herald, October 28, 1886; Springfield (OH) Globe-Republican, October 31, 1886; Christian Recorder, November 11, 1886; Boston Herald, November 22, 1886; Grand Forks (ND) Daily Herald, January 3, 1887

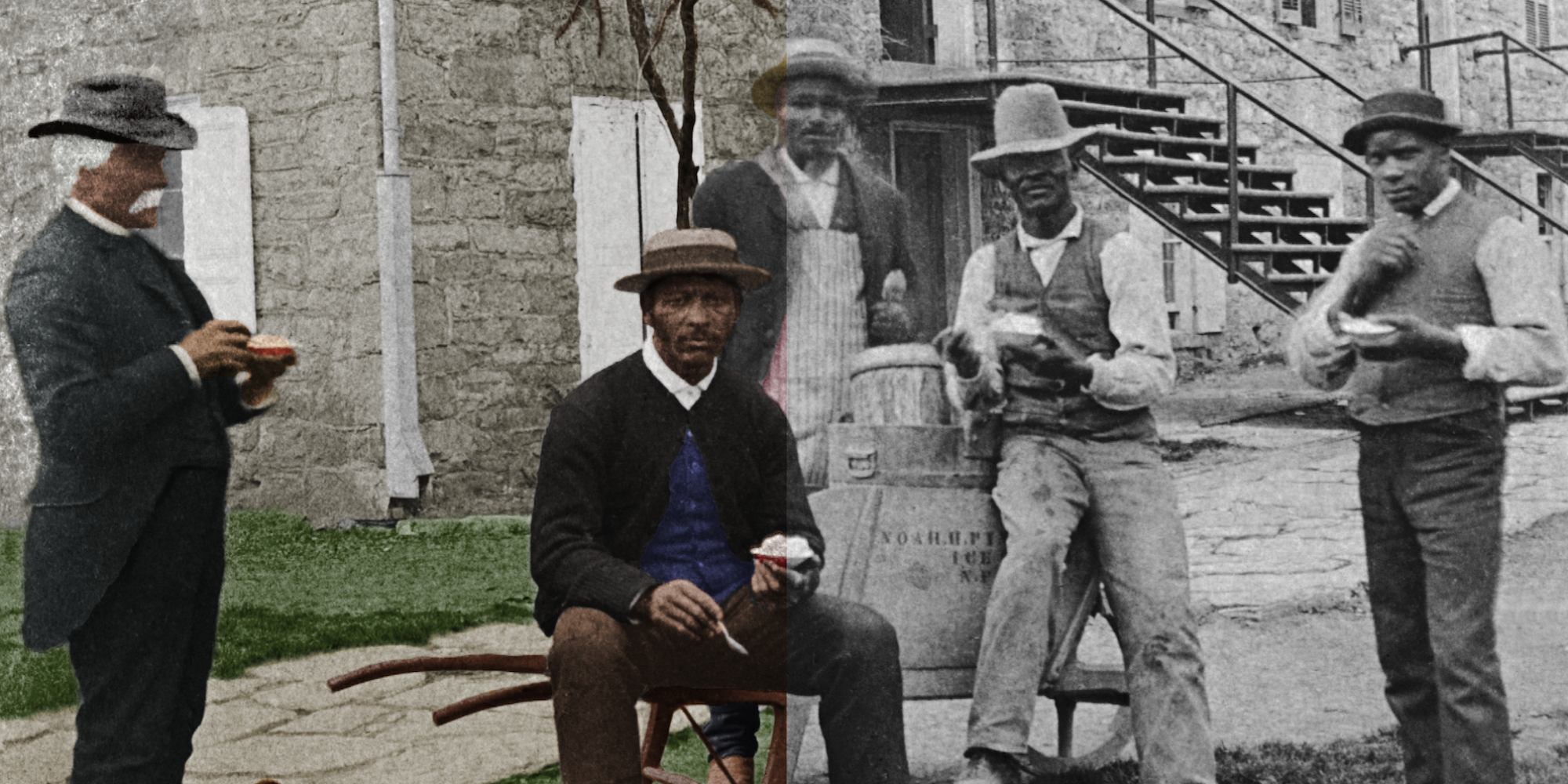

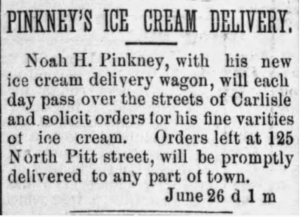

1888 || Pinkney begins selling ice cream

Noah Pinkney began selling ice cream in Carlisle in 1888. “Pink” or “Uncle Noah” was a former slave from Virginia who had served in the Union army and worked in Harrisburg after the Civil War. By the mid-1880s, he had relocated to Carlisle and was proving successful as an entrepreneur in town, someone who sold all kinds of exotic foods to the students at Dickinson College –everything from pretzels to oysters to ice cream. For years, Pinkney was allowed to roam the campus selling his treats, but by the mid-1890s he was compelled to move off-campus and sell outside the college gates. Eventually, Pinkney and his wife Carrie (or “Aunt Noah” as some of the students called her) opened a restaurant out of their residence on West Street. Their place became a favorite hangout for Dickinson students and Pinkney became a clear favorite in the memories of generations of Dickinsonians.

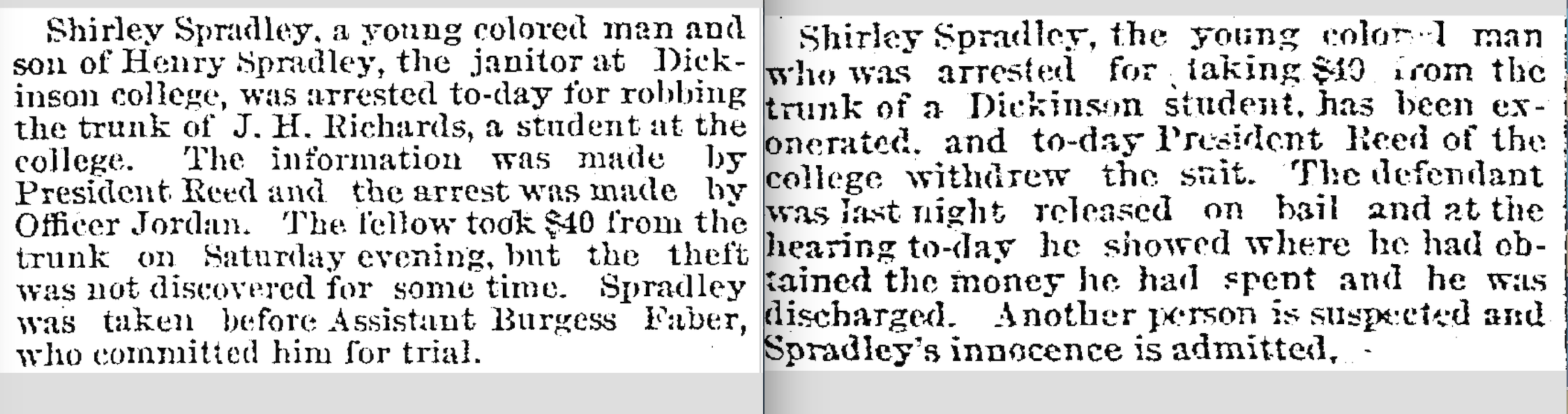

1892 || Spradley’s son falsely accused of stealing

In December 1892, the son of Dickinson’s longtime and much-beloved janitor was accused by the president of the college of stealing from a student. Shirley Spradley, age 18, was then living and working on campus. His father had been janitor and bell ringer at West College since the late 1870s. The Spradleys had kept a family residence inside of South College. But when a Dickinson student discovered that $40 had gone missing from his trunk, despite the familiarity everyone had with the Spradley family, they immediately assumed the worst of the young black man who was spending money in town. George Reed, college president at that time, made a formal complaint to the Carlisle police, who quickly arrested young Spradley. Given the tales about an earlier near-lynching episode from the 1870s over a similar accusation of theft, one can only imagine how frightened the Spradleys were over the fate of their son. Yet, the story ended with some measure of justice. At a preliminary hearing the day after his arrest, Shirley was able to prove how he had obtained his cash and the charges were quickly dismissed. It is not clear, however, if President Reed ever apologized to the family.

Sources: Harrisburg Telegraph, December 21, 1892; Harrisburg Telegraph, December 22, 1892

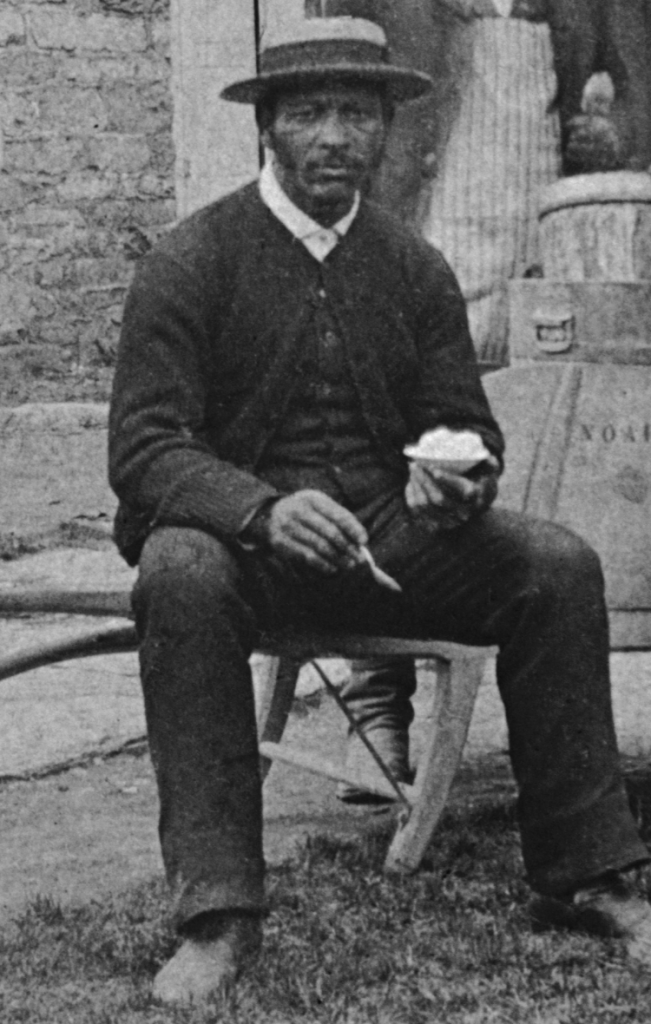

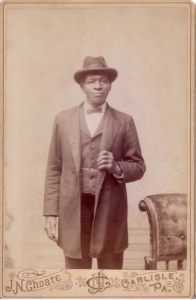

1897 || College closes to host Spradley’s funeral

When college janitor Henry Spradley died in April 1897, his memorial service brought together black and white in Carlisle in a powerfully compelling way. Concerned that the West Street A.M.E. Church was too small to hold the anticipated crowd, Dickinson College agreed to cancel classes in the afternoon and host the service inside the new Bosler Hall. Spradley’s pallbearers were fellow janitors at Dickinson and other leaders of the local black community. The attendees included nearly the entire study body of the college, along with faculty and staff and extended family and friends. To commemorate his life and service, the college also apparently commissioned a memorial card from local photographer J.N. Choate, who seems to have had an old negative of

Spradley in his files or perhaps was given one of a younger Spradley taken by someone else. Choate was the photographer in Carlisle best known for capturing “before and after” images of assimilated Indians and sometimes of former slaves. The younger vibrant Spradley only dimly resembled his later self, after he had struggled for years with heart disease and rheumatism. But the former stone mason’s long, gnarled hands were a consistent presence in these various images, whether dressed up as a Union veteran and freed man in his 30s or early 40s, or seated with his young son and fellow janitor Robert Young sometime in his 50s, or while resting outside near East College enjoying ice cream in his 60s. By the end of his life, approaching 70, Spradley had become not only a familiar and beloved presence on campus, but also a noted force in Carlisle’s public life. He was a leader in his church and in various fraternal organizations. When necessary, he could also become a civil rights activist. In 1888, both he and Robert Young had helped organize a protest meeting against color discrimination in the town. They each spoke. There were difficult moments, such as earlier in the decade when his son Shirley Spradley had been falsely accused of theft. But there were also proud achievements that showed the promise of equality, such as being included in the ground-breaking ceremonies for Denny Hall in the spring of 1895. A former escaped slave from Virginia, Spradley had built a respectable, even distinguished, life for himself in Pennsylvania. He was buried with other black Civil War veterans in Lincoln Cemetery, near the college campus on the west side of town. However, that cemetery later became abandoned and was redeveloped as a local park. Now, the only public reminiscence of Spradley at Dickinson or in Carlisle is a marker in Memorial Park that includes a list of names of men once buried there, including Henry W. Spradley.

Sources: Richard L. Tritt, “John Nicholas Choate: A Cumberland County Photographer,” Cumberland County History 13 (Winter 1996): 77-90 [WEB]