College Founding (1780s – 1830s)

The founders of Dickinson College believed in the principles of the enlightenment and yet still found ways to rationalize ownership of other human beings. Some of the institution’s early leading men, such as John Dickinson and Benjamin Rush, did help spearhead the fight against eighteenth-century slavery, but they also owned slaves and delayed emancipating them for years. Enslaved labor helped to construct some of the earliest college buildings, and slaveholders dominated among the original boards of trustees. Pennsylvania had adopted a pioneering gradual abolition statute in 1780, but there were individual slaves being held in Cumberland County and by Dickinsonians for decades afterward. From the beginning, slavery was a controversial but significant factor in the life of this Northern college.

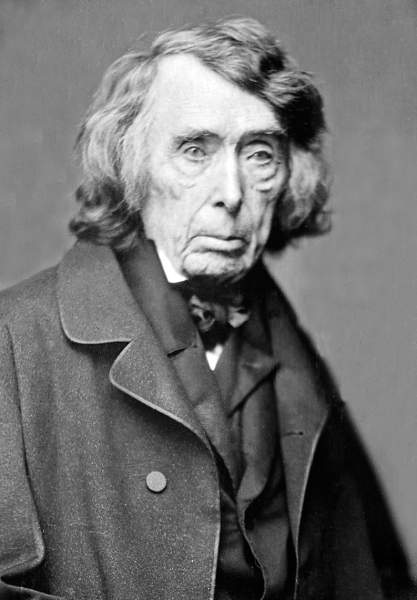

Sectional Crisis (1840s – 1860s)

Graduates of Dickinson College helped build and sustain the peculiar institution of American slavery during the middle of the nineteenth century. One of the nation’s largest slaveholders was a Dickinsonian. One of the nation’s most aggressive fugitive slave commissioners was a Dickinsonian. But most important, the nation’s leading pro-slavery jurist, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney (Class of 1795) was a Dickinsonian. There were also plenty of Dickinsonians who hated slavery and fought to create “a new birth of freedom” for the Union they loved. Yet throughout the Civil War era, the school could never quite escape its well-known connection with pro-slavery forces.

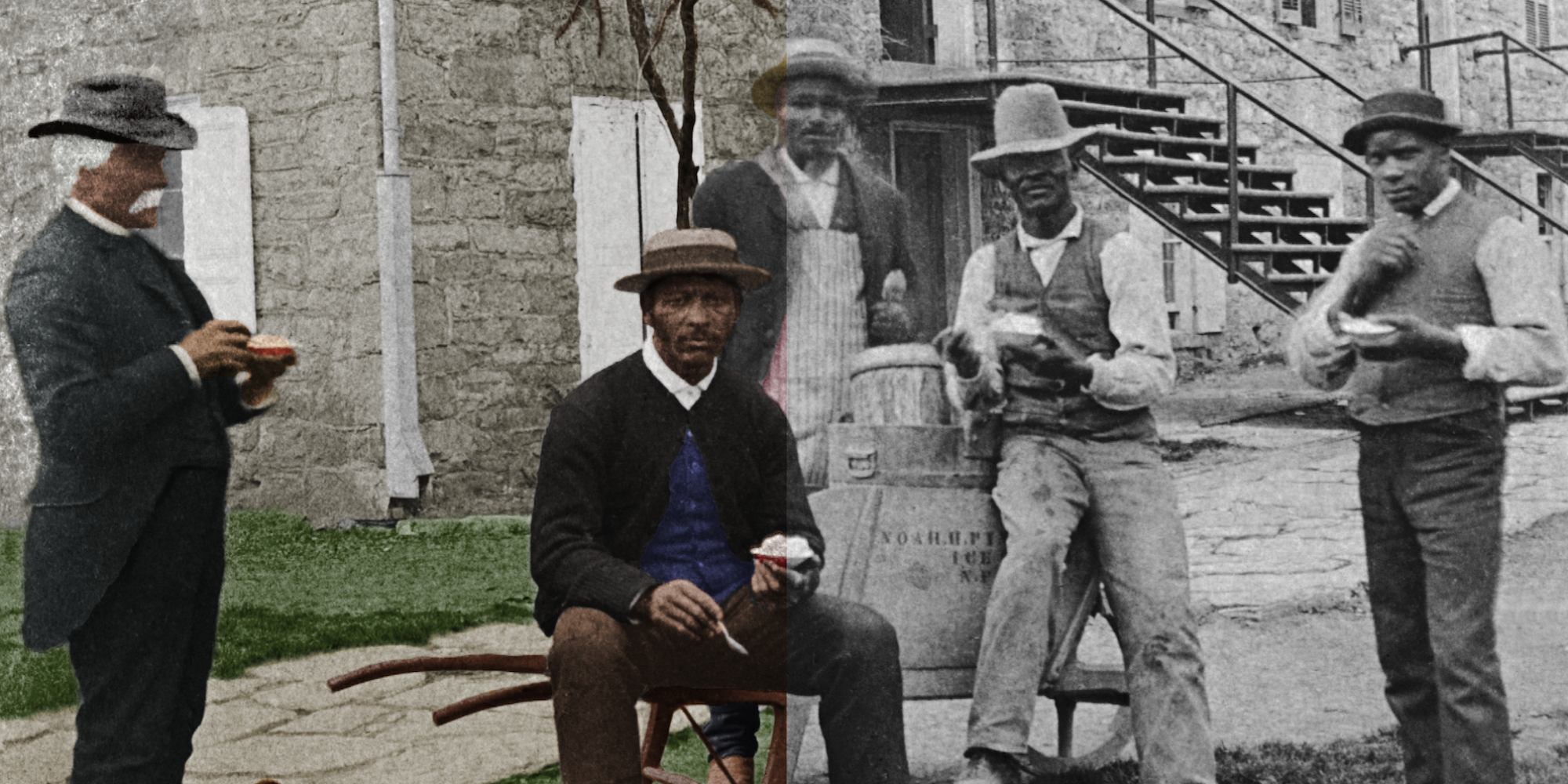

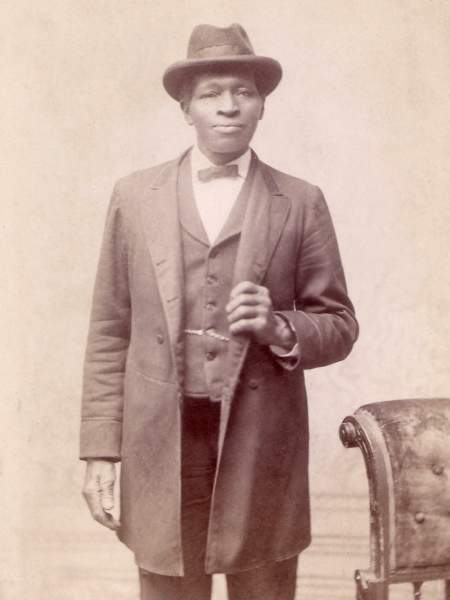

Freedom’s Legacy (1870s – 1890s)

Black families lived on the Dickinson campus throughout the nineteenth century. Black men –some born free, others former slaves– worked with faculty and students as janitorial staff, laborers and as local vendors. Some, like longtime janitor Henry W. Spradley, became integral and beloved members of the community. But freedom did not always mean equality. When one janitor pushed to have his son become a student on campus in the 1880s, there was resistance and a national debate. Eventually, by the turn of the twentieth century, black men and women began to participate on campus as full-fledged students, but the road toward equality at Dickinson and around Carlisle was never easy.