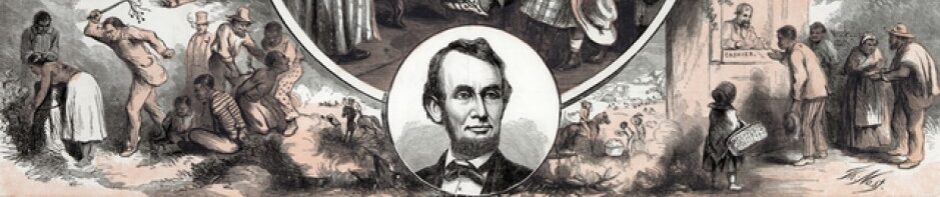

January 1, 1863 was an important day at the former plantation of John Joyner Smith near Port Royal, South Carolina. Thousands of people, white and black, gathered to celebrate “Emancipation Day” and the resulting newspaper reports, diary accounts and recollections probably make this the single most notable and best documented emancipation “moment” in the South.

January 1, 1863 was an important day at the former plantation of John Joyner Smith near Port Royal, South Carolina. Thousands of people, white and black, gathered to celebrate “Emancipation Day” and the resulting newspaper reports, diary accounts and recollections probably make this the single most notable and best documented emancipation “moment” in the South.

The story behind Port Royal in Beaufort District (or county) South Carolina is crucial for understanding how emancipation actually worked on the ground. Since November 1861, Federal troops had occupied the area and white Union army officers and a diverse collection of abolitionist missionaries had since been endeavoring to train and educate former slaves at the plantation site they now called Camp Saxton, after Union general Rufus Saxton who was in charge of the military district. And since August 1862, the army officers in the area had quietly been authorized by the War Department to organize what might be considered the first official black regiment in the Union army, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers (and which later became the 33rd United States Colored Infantry). Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a noted Massachusetts abolitionist and former ally of John Brown’s, commanded these men. Higginson kept a camp diary which he later published in The Atlantic magazine in 1864 and 1865 as “Leaves from an Officer’s Journal.” He also later adapted these entries in his well-regarded post-war memoir, Army Life in a Black Regiment (Boston, 1870). Below you will find an excerpt from Higginson’s journal on Emancipation Day as it appeared in the December 1864 edition of The Atlantic. In this famous account, Higginson describes the “electric” scene which occurred at Camp Saxton following the reading of Lincoln’s September 22, 1862 Emancipation Proclamation as former slaves in the audience began spontaneously to sing “America.” (Please note they had not yet received the text of the final or what Higginson would term the “Second” Emancipation Proclamation which Lincoln was signing that very day.) In a second entry from January 12th, also excerpted below, Higginson described the reading of that final proclamation. And we have also included here accounts of the Emancipation Day celebrations from the letters of the regiment’s surgeon, Dr. Seth Rogers, the diaries and letters of teachers Charlotte Forten and Harriet Ware, and recollections by Lt. Col. Charles T. Towbridge, the second commanding officer of the regiment, and Susie Baker King Taylor, a runaway slave from Savannah, who was 14-years-old at the time and present at Camp Saxton that day. Susie Baker was self-educated and also served as a teacher for the soldiers. She later married one of the men, Edward King, and after the war became the only black woman to publish a memoir of her Civil War experiences, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers (1902).

Camp Diary, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, [Thursday] January 1, 1863 (evening).

“…About ten o’clock the people began to collect by land, and also by water,–in steamers sent by General [Rufus] Saxton for the purpose; and from that time all the avenues of approach were thronged. The multitude were chiefly colored women, with gay handkerchiefs on their heads, and a sprinkling of men, with that peculiarly respectable look which these people always have on Sundays and holidays. There were many white visitors also,–ladies on horseback and in carriages, superintendents and teachers, officers and cavalry-men. Our companies were marched to the neighborhood of the platform, and allowed to sit or stand, as at the Sunday services; the platform was occupied by ladies and dignitaries, and by the band of the Eighth Maine, which kindly volunteered for the occasion; the colored people filled up all the vacant openings in the beautiful grove around, and there was a cordon of mounted visitors beyond. Above, the great live-oak branches and their trailing moss; beyond the people, a glimpse of the blue river.

The services began at half-past eleven o’clock, with prayer by our chaplain, Mr. [James H.] Fowler, who is always, on such occasions, simple, reverential, and impressive. Then the President’s Proclamation [from September 22, 1862] was read by Dr. W. H. Brisbane, a thing infinitely appropriate, a South-Carolinian addressing South-Carolinians; for he was reared among these very islands, and here long since emancipated his own slaves. Then the colors were presented to us by the Rev. Mr. French, a chaplain who brought them from the donors in New York. All this was according to the programme. Then followed an incident so simple, so touching, so utterly unexpected and startling, that I can scarcely believe it on recalling, though it gave the key-note to the whole day. The very moment the speaker had ceased, and just as I took and waved the flag, which now for the first time meant anything to these poor people, there suddenly arose, close beside the platform, a strong male voice, (but rather cracked and elderly,) into which two women’s voices instantly blended, singing, as if by an impulse that could no more be repressed than the morning note of the song-sparrow,–

“My Country, ’tis of thee,

Sweet land of liberty,

Of thee I sing!”

People looked at each other, and then at us on the platform, to see whence came, this interruption, not set down in the bills. Firmly and irrepressibly the quavering voices sang on, verse after verse; others of the colored people joined in; some whites on the platform began, but I motioned them to silence. I never saw anything so electric; it made all other words cheap; it seemed the choked voice of a race at last unloosed. Nothing could be more wonderfully unconscious; art could not have dreamed of a tribute to the day of jubilee that should be so affecting; history will not believe it; and when I came to speak of it, after it was ended, tears were everywhere. If you could have heard how quaint and innocent it was! Old Tiff and his children might have sung it; and close before me was a little slave-boy, almost white, who seemed to belong to the party, and even he must join in. Just think of it!–the first day they had ever had a country, the first flag they had ever seen which promised anything to their people, and here, while mere spectators stood in silence, waiting for my stupid words, these simple souls burst out in their lay, as if they were by their own hearths at home! When they stopped, there was nothing to do for it but to speak, and I went on; but the life of the whole day was in those unknown people’s song.

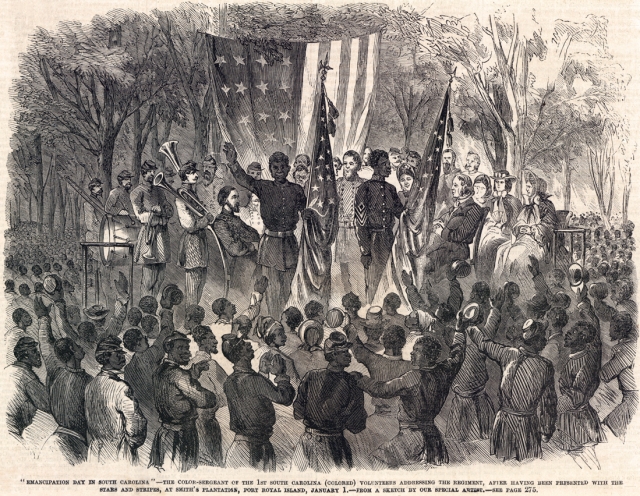

Receiving the flags, I gave them into the hands of two fine-looking men, jet-black, as color-guard, and they also spoke, and very effectively,–Sergeant Prince Rivers and Corporal Robert Sutton [depicted in the image above from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper]. The regiment sang “Marching Along,” and then General Saxton spoke, in his own simple, manly way, and Mrs. Frances D. Gage spoke very sensibly to the women, and Judge Stickney, from Florida, added something; then some gentlemen sang an ode, and the regiment the John Brown song, and then they went to their beef and molasses. Everything was very orderly, and they seemed to have a very gay time. Most of the visitors had far to go, and so dispersed before dress-parade, though the band stayed to enliven it. In the evening we had letters from home, and General Saxton had a reception at his house, from which I excused myself; and so ended one of the most enthusiastic and happy gatherings I ever knew. The day was perfect, and there was nothing but success. [From The Atlantic, December 1864]

Higginson also recorded the response of his troops to the reading of the final Emancipation Proclamation (January 1, 1863) when it finally arrived to Beaufort on Saturday, January 10, 1863. Though stirring in a somber way, this scene appears far less “electric” and Higginson seems far more patronizing in his attitude toward his men.

[Monday] January 12, 1863:

“Many things glide by without time to narrate them. On Saturday we had mail with the President’s Second Message of Emancipation, and the next day it was read to the men. The words themselves did not stir them very much, because they have been often told that they were free, especially on New Year’s Day, and, being unversed in politics, they do not understand, as well as we do, the importance of each additional guaranty. But the chaplain spoke to them afterwards very effectively, as usual; and then I proposed to them to hold up their hands and pledge themselves to be faithful to those still in bondage. They entered heartily into this, and the scene was quite impressive, beneath the great oak branches. I heard afterwards that only one man refused to raise his hand, saying bluntly that his wife was out of slavery with him, and he did not care to fight. The other soldiers of his company were very indignant, and shoved him about among them while marching back to their quarters, calling him ‘Coward.’ I was glad of their exhibition of feeling, though it is very possible that the one who had thus the moral courage to stand alone among his comrades might be more reliable, on a pinch, than some who yielded a more ready assent. But the whole response, on their part, was very hearty, and will be a good thing to which to hold them hereafter, at any time of discouragement or demoralization –which was my chief reason for proposing it. With their simple natures it is a great thing to tie them to some definite committal; they never forget a marked occurrence, and never seem disposed to evade a pledge.” (From The Atlantic, January 1865)

Dr. Seth Rogers from Massachusetts was an old friend of Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson who had arrived at Camp Saxton in December 1862 to serve as the regiment’s chief surgeon. Rogers wrote numerous letters to his wife during his single year of service with the regiment that are now available online through the efforts of professors and students at the University of North Florida. Like Higginson, Rogers was deeply moved by the spontaneous singing of “America” by the former slaves present at Camp Saxton on Emancipation Day.

Letter from Dr. Seth Rogers to wife Hannah Mitchell Rogers, January 1, 1863:

“This is the evening of the most eventful day of my life. Our barbeque was a most wonderful success. Two steamboats came loaded with people from Beaufort, St. Helena Island and Hilton Head. Among the visitors were some of my new acquaintances, [including] my friend, Mr. Hall of the voyage Delaware. But the dearest friend I found among them was Miss [Charlotte] Forten, whom you remember. She is a teacher of the freed children on St. Helena Island. Gen [Rufus] Saxton and his father and others came from Beaufort, and several cavalry officers hovered around the outskirts of our multitude of black soldiers and civilians, and in the centre of all was the speakers’ stand where the General and our Colonel and some others, with the band, performed the ceremonies of the day. Several good speeches were made, but the most impressive scene was that which occurred at the presentation of the Dr. Cheever flag to our regiment. After the presentation speech had been made, and just as Col. Higginson advanced to take the flag and respond, a negro woman standing near began to sing “America”, and soon many voices of freedmen and women joined in the beautiful hymn, and sang it so touchingly that every one was thrilled beyond measure. Nothing could have been more unexpected or more inspiring. The President’s [September 22, 1862] proclamation and General Saxton’s New Year’s greeting had been read, and this spontaneous outburst of love and loyalty to a country that has heretofore so terribly wronged these blacks, was the birth of a new hope in the honesty of her intention. I most earnestly trust they not hope in vain. Col. H. was so much inspired by the remarkable thought of, and singing of, the hymn that he made one of his most effective speeches. Then came Gen. Saxton with a most earnest and brotherly speech to the blacks and then Mrs. Frances D. Gage, and finally all joined in the John Brown hymn, and then to dinner. A hundred things of interest occurred which I have not time to relate. Everybody was happy in the bright sunshine, and in the great hope.”

Charlotte Forten, a black abolitionist from Philadelphia, was a friend of Dr. Rogers and was teaching freed slaves at nearby St. Helena Island in 1862 and 1863. She attended the Emancipation Day ceremonies and recorded many of the same details of the remarkable event:

Thursday, New Year’s Day, 1863.

“The most glorious day this nation has yet seen, I think. I rose early-an event here-and early we started, with an old borrowed carriage and a remarkably slow horse. Whither were we going? thou wilt ask, dearest A. To the ferry; thence to Camp Saxton, to the Celebration. From the Ferry to the camp the “Flora” took us….I cannot give a regular chronicle of the day. It is impossible. I was in such a state of excitement. It all seemed and seems still like a brilliant dream. Dr. R[ogers] and I talked all the time, I know, while he showed me the camp and all the arrangements. They have a beautiful situation, on the grounds once occupied by a very old fort, “De La Ribanchine,” built in 1629 or 30. Some of the walls are still standing. Dr. R[ogers] had made quite a good hospital out of an old gin house. I went over it. There are only a few invalids in it, at present. I saw everything; the kitchens, cooking arrangements, and all. Then we took seats on the platform.

The meeting was held in a beautiful grove, a live-oak grove, adjoining the camp. It is the largest one I have yet seen; but I don’t think the moss pendants are quite as beautiful as they are on St. Helena. As I sat on the stand and looked around on the various groups, I thought I had never seen a sight so beautiful. There were the black soldiers, in their blue coats and scarlet pants, the officers of this and other regiments in their handsome uniforms, and crowds of lookers-on, men, women and children, grouped in various attitudes, under the trees. The faces of all wore a happy, eager, expectant look.

The exercises commenced by a prayer from Rev. Mr. Fowler, Chaplain of the reg. An ode written for the occasion by Prof. [John] Zachos, originally [in] Greek … was read by himself, and then sung by the whites. Col. H [igginson] introduced Dr. Brisbane in a few elegant and graceful words. He (Dr. B.) read the President’s [Emancipation] Proclamation, which was warmly cheered. Then the beautiful flags presented by Dr. Cheever’s Church [in New York] were presented to Col. H[igginson] for the Reg[iment] in an excellent and enthusiastic speech, by Rev. Mr. [Mansfield] French. Immediately at the conclusion, some of the colored people of their own accord sang “My Country Tis of Thee.” It was a touching and beautiful incident, and Col. Higginson, in accepting the flags made it the occasion of some happy remarks. He said that that tribute was far more effective than any speech he c’ld make. He spoke for some time, and all that he said was grand, glorious. He seemed inspired.

Nothing c ‘ld have been better, more perfect. And Dr. R[ogers] told me afterward that the Col. was much affected. That tears were in his eyes. He is as “Whittier says, truly a “sure man.” The men all admire and love him. There is a great deal of personal magnetism about him, and his kindness is proverbial. After he had done speaking he delivered the flags to the color-bearers with a few very impressive remarks to them. They each then, Sgt. Prince Rivers and [Cpl.] Robert Sutton, made very good speeches indeed, and were loudly cheered….Ah, what a grand, glorious day this has been. The dawn of freedom which it heralds may not break upon us at once; but it will surely come, and sooner, I believe, than we have ever dared hope before.”

[Source: Ray Allen Billington, “A Social Experiment: The Port Royal Journal of Charlotte L. Forten, 1862-1863,” Journal of Negro History 35 (July 1950): 233-264]

Harriet Ware (1834-1920) was another northern teacher who had come down to Port Royal in 1862 . Here is an excerpt from her letter describing the events on January 1. Like everyone else, Ware was struck by the singing of “America,” but alone among the correspondents from that day, she took special notice of the words of Corporal Robert Sutton:

“It is simply impossible to give you any adequate idea of the next three hours. Picture the scene to yourself if you can, — I will tell you all the facts, — but if I could transcribe every word that was uttered, still nothing could convey to you any conception of the solemnity and interest of the occasion. Mr. Judd, General Superintendent of the Island, was master of ceremonies, and first introduced Mr. Fowler, the Chaplain, who made a prayer, — then he announced that the President’s Proclamation would be read, and General Saxton’s also, by a gentleman who would be introduced by Colonel Higginson. And he rose amid perfect silence, his clear rich voice falling most deliciously on the ear as he began to speak. He said that the Proclamation would be read “by a South Carolinian to South Carolinians” — a man who many years before had carried the same glad tidings to his own slaves now brought them to them, and with a few most pertinent words introduced Dr. Brisbane, one of the tax-commissioners here now, who read both proclamations extremely well. They cheered most heartily at the President’s name, and at the close gave nine with a will for General “Saxby,” as they call him. Mr. Zachos then read an ode he had written for the occasion, which was sung by the white people (printed copies being distributed, he did not line it as is the fashion in these parts) — to “Scots wha hae.” I forgot to mention that there was a band on the platform which discoursed excellent music from time to time. At this stage of the proceedings Mr. French rose and, in a short address, presented to Colonel Higginson from friends in New York a beautiful silk flag, on which was embroidered the name of the regiment and “The Year of Jubilee has come!”

Just as Colonel Higginson had taken the flag and was opening his lips to answer (his face while Mr. French was speaking was a beautiful sight), a single woman’s voice below us near the corner of the platform began singing “My Country, ’tis of thee.” It was very sweet and low — gradually other voices about her joined in and it began to spread up to the platform, till Colonel Higginson turned and said, “Leave it to them,” when the negroes sang it to the end. He stood with the flag in one hand looking down at them, and when the song ceased, his own words flowed as musically, saying that he could give no answer so appropriate and touching as had just been made. In all the singing he had heard from them, that song he had never heard before — they never could have truly sung “my country” till that day. He talked in the most charming manner for over half an hour, keeping every one’s attention, the negroes’ upturned faces as interested as any, if not quite as comprehending. Then he called Sergeant Rivers and delivered the flag to his keeping, with the most solemn words, telling him that his life was chained to it and he must die to defend it. Prince Rivers looked him in the eye while he spoke, and when he ended with a “Do you understand?” which must have thrilled through every one, answered most earnestly, “Yas, Sar.” The Colonel then, with the same solemnity, gave into the charge of Corporal Robert Sutton a bunting flag of the same size; then stepping back stood with folded arms and bare head while the two men spoke in turn to their countrymen. Rivers is a very smart fellow, has been North and is heart and soul in the regiment and against the “Seceshky.” He spoke well; but Sutton with his plain common sense and simpler language spoke better. He made telling points; told them there was not one in that crowd but had sister, brother, or some relation among the rebels still; that all was not done because they were so happily off, that they should not be content till all their people were as well off, if they died in helping them; and when he ended with an appeal to them to above all follow after their Great Captain, Jesus, who never was defeated there were many moist eyes in the crowd.”

[Source: Elizabeth Ware Pearson, ed., Letters from Port Royal, 1862-1868 (Boston: W.B. Clarke, 1906), 131-2]

Rev. Mansfield French, who presented the “colors” to the regiment on that day –two silk flags, one the Stars & Stripes, and the other the US coat of arms– described his version of events in a letter written the next day to Secretary of Treasury Salmon P. Chase:

“Yesterday was a “day of Jubilee” with us. At the camp of 1st Reg. S.C. Vol. were assembled thousands of the colored people to celebrate their birthday. Rev Dr.Brisbane read the Prest. Proclamation, being introduced by Col Higginson,(1st S.C. Vol), “as formerly of S. Carolina & representative still of S.Carolina. An ode by Prof. Zachos was sung (copy enclosed) and a Stand of beautiful colors was presented to the Regt. At the close of my remarks,a most wonderful thing happened. As I passed the flag to Col. Higginson & before he could speak the colored people with no previous concert whatever & without any suggestion from any person, broke forth in the song, “My country tis of thee” &c God was truly manifest in it. None of us recollect ever having heard the song from a colored man or woman before. At the close of Col H. reply he called to the stand Sergeant Prince Rivers, & Corporal Jordan [sic] giving one the silk flag & the other the bunting one. Each then with the flag in hand addressed the audience. No friend of the colored man was made ashamed by these addresses. Prince said he would die before surrendering it, & that he wanted to show it to all the old masters. The Corporal, said he could not rest satisfied while so many of their kindred were left in chains. He appealed to the regiment in their behalf & closed by saying they must show their flag to Jefferson Davis in Richmond.”

[Source: Mansfield French to Salmon P. Chase, Beaufort, SC, January 2, 1863, excerpted from John P. Niven, ed., The Salmon P. Chase Papers: Volume 3, Correspondence, 1858 – March 1863 (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1996), 3: 352]

Susie Baker King Taylor also recalled this remarkable day in her 1902 memoir, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, which is now available online through the University of North Carolina’s invaluable project, “Documenting the American South.” Taylor’s memory was dimmed somewhat by the passage of time, but she clearly never forgot how the camp “seemed overflowing with fun and frolic” on that first Emancipation Day.

“On the first of January, 1863, we held services for the purpose of listening to the reading of President Lincoln’s proclamation by Dr. W. H. Brisbane, and the presentation of two beautiful stands of colors, one from a lady in Connecticut, and the other from Rev. Mr. Cheever. The presentation speech was made by Chaplain French. It was a glorious day for us all, and we enjoyed every minute of it, and as a fitting close and the crowning event of this occasion we had a grand barbecue. A number of oxen were roasted whole, and we had a fine feast. Although not served as tastily or correctly as it would have been at home, yet it was enjoyed with keen appetites and relish. The soldiers had a good time. They sang or shouted “Hurrah!” all through the camp, and seemed overflowing with fun and frolic until taps were sounded, when many, no doubt, dreamt of this memorable day.”

Lt. Col. Charles T. Trowbridge, an officer from New York who had originally helped recruit the soldiers of the 1st South Carolina and who succeeded Col. Higginson in command of the regiment, recalled one particular element of the Emancipation Day celebrations in his final order disbanding the men on February 9, 1866:

“The flag which was presented to us by the Rev. George B. Cheever and his congregation, of New York city, on the 1st of January, 1863,–the day when Lincoln’s immortal proclamation of freedom was given to the world,–and which you have borne so nobly through the war, is now to be rolled up forever and deposited in our nation’s capital. And while there it shall rest, with the battles in which you have participated inscribed upon its folds, it will be a source of pride to us all to remember that it has never been disgraced by a cowardly faltering in the hour of danger, or polluted by a traitor’s touch.”

The former Camp Saxton site near Port Royal has been part of the National Register of Historic Places since 1995. You can view the full text of the original application for the National Register, with all of its vivid details and useful citations, here courtesy of the South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

Pingback: Emancipation! (January 1st, 1863) « Live Free and Draw by Marek Bennett

Thanks for this wonderful piece. In Beaufort, where we host the Reconstruction Era National Historical Park and Network we have a non-profit that is creating a resource center for the Reconstruction Educators Network

http://www.reconstructionbeaufort.org

http://www.sharingcommonground.com

You may be interested in the above.

Best wishes Billy Keyserling

My wife and I visited Fripp Island in the summer of 2012. Having read of the historic first reading of the Emancipation proclamation in Port Royale in 1863, we determined to visit the live oak grove where the historic reading took place. After searching for the site with the help of the local Sheriff, we were discouraged to learn that the site is now a part of the local U.S. military hospital grounds, and is off limits to civilians and tourists. Rev. John Specht