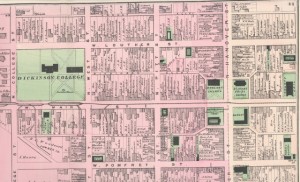

A new political movement born out of New York and Philadelphia spread across the country, emerging in Cumberland County in 1854, shaping its politics for more than two years. Spurred by anti-Catholic and anti-immigration sentiment, the Know Nothing party grew to significant prominence if only for a short period during the mid 1850s. Reverend Otis H. Tiffany was Dickinson College’s professor of mathematics and president of the Know Nothing State Council. Tiffany, a prominent leader and adamant speaker for the Know Nothing party, gave a public lecture at Carlisle Union Fire Hall on November 16, 1854 on the Protestant origins of American freedoms and on the dangers of the vast immigration and rapid naturalization of foreigners. Tiffany commented, “No foreigner is competent to discharge the duties of an American until he ceases to be identified with the land which gave him birth.”

A new political movement born out of New York and Philadelphia spread across the country, emerging in Cumberland County in 1854, shaping its politics for more than two years. Spurred by anti-Catholic and anti-immigration sentiment, the Know Nothing party grew to significant prominence if only for a short period during the mid 1850s. Reverend Otis H. Tiffany was Dickinson College’s professor of mathematics and president of the Know Nothing State Council. Tiffany, a prominent leader and adamant speaker for the Know Nothing party, gave a public lecture at Carlisle Union Fire Hall on November 16, 1854 on the Protestant origins of American freedoms and on the dangers of the vast immigration and rapid naturalization of foreigners. Tiffany commented, “No foreigner is competent to discharge the duties of an American until he ceases to be identified with the land which gave him birth.”

Much of the sources on the Know Nothings in Cumberland County are derived from local newspapers such as the Carlisle American, Carlisle Herald, Shippensburg News and American Volunteer. During this time, Tiffany and several other professors at Dickinson College had been active in the Know-Nothing movement. While most of the papers were supportive, the American Volunteer was the most negative, commonly criticizing the party and the involvement of Tiffany and others from Dickinson College. On August 23, 1857 with the Know Nothing movement nearly dissolved, the Volunteer cited the negative effects brought on by the faculty “by their constant dabbling in politics…But we gained our point which was to drive them from their Know-Nothing lodges to their duties in the College.”

While unsuccessful in sustaining the Know Nothing movement in Cumberland County, Tiffany was and remained a respected leader throughout the community. In Alexander Kelly McClure‘s Old Time Notes of Pennsylvania, he comments on the merits of Tiffany. McClure, a prominent Pennsylvania politician and journalist, regarded Tiffany as the ablest of all the Know-Nothing leaders.

“The one who stood out most conspicuous as an active politician and consistent Christian gentleman was Dr. Tiffany, who, as I have stated, accomplished the union of the opposition forces at the conference in 1855. He was not only a man of unusual eloquence, but a sagacious leader in Church and State, and always commanded the respect of all who came in contact with him, whether supporting or opposing him.”

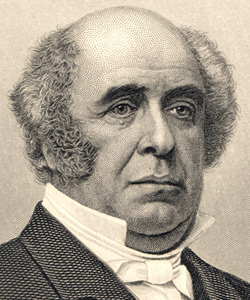

When Dickinson College President Jesse Peck arrived in Staunton, Virginia, for a conference in the spring of 1849, local authorities detained him as a result of a prank by Dickinson students. As the Richmond (VA) Examiner reported:

When Dickinson College President Jesse Peck arrived in Staunton, Virginia, for a conference in the spring of 1849, local authorities detained him as a result of a prank by Dickinson students. As the Richmond (VA) Examiner reported: