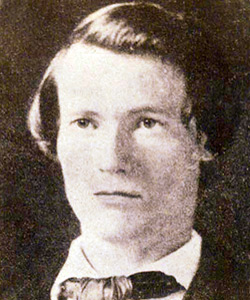

Albert Hazlett was among several of John Brown’s raiders who were not with their leader on the morning of October 18, 1859 when US Marines attacked the engine house at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Instead, Hazlett and Osborne Anderson watched the short battle from afar. The two men had left Harpers Ferry undetected late on October 17. After they could not find the five raiders who also escaped, they decided to head north – which eventually brought them into southern Pennsylvania. While Anderson lived to publish a book in 1861 about his experience, Hazlett was arrested in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania on October 22, 1859. Local authorities, however, at first thought that they had in custody “a man supposed to be Capt. Cook.” (John E. Cook was arrested three days later outside of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania). The initial confusion offered an opportunity for Hazlett, who claimed that he was actually William Harrison and had nothing to do with Brown’s raid. On October 29 Hazlett appeared before a judge in Carlisle on a writ of habeas corpus, but Hazlett’s claim that he was the wrong person failed to convince the judge. While “there is no evidence that we have any man in our custody named Albert Hazlett,” the court ruled that “we are satisfied that a monstrous crime has been committed [and] that the prisoner…participated in it.” Hazlett was sent back to Charlestown, Virginia on November 5 for a trial and was executed on March 16, 1860. Historian David Reynolds, who wrote John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, notes that the judge sent Hazlett back to Virginia “even though the evidence linking him to Harpers Ferry was circumstantial.”

Albert Hazlett was among several of John Brown’s raiders who were not with their leader on the morning of October 18, 1859 when US Marines attacked the engine house at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Instead, Hazlett and Osborne Anderson watched the short battle from afar. The two men had left Harpers Ferry undetected late on October 17. After they could not find the five raiders who also escaped, they decided to head north – which eventually brought them into southern Pennsylvania. While Anderson lived to publish a book in 1861 about his experience, Hazlett was arrested in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania on October 22, 1859. Local authorities, however, at first thought that they had in custody “a man supposed to be Capt. Cook.” (John E. Cook was arrested three days later outside of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania). The initial confusion offered an opportunity for Hazlett, who claimed that he was actually William Harrison and had nothing to do with Brown’s raid. On October 29 Hazlett appeared before a judge in Carlisle on a writ of habeas corpus, but Hazlett’s claim that he was the wrong person failed to convince the judge. While “there is no evidence that we have any man in our custody named Albert Hazlett,” the court ruled that “we are satisfied that a monstrous crime has been committed [and] that the prisoner…participated in it.” Hazlett was sent back to Charlestown, Virginia on November 5 for a trial and was executed on March 16, 1860. Historian David Reynolds, who wrote John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, notes that the judge sent Hazlett back to Virginia “even though the evidence linking him to Harpers Ferry was circumstantial.”

Author: sailerd

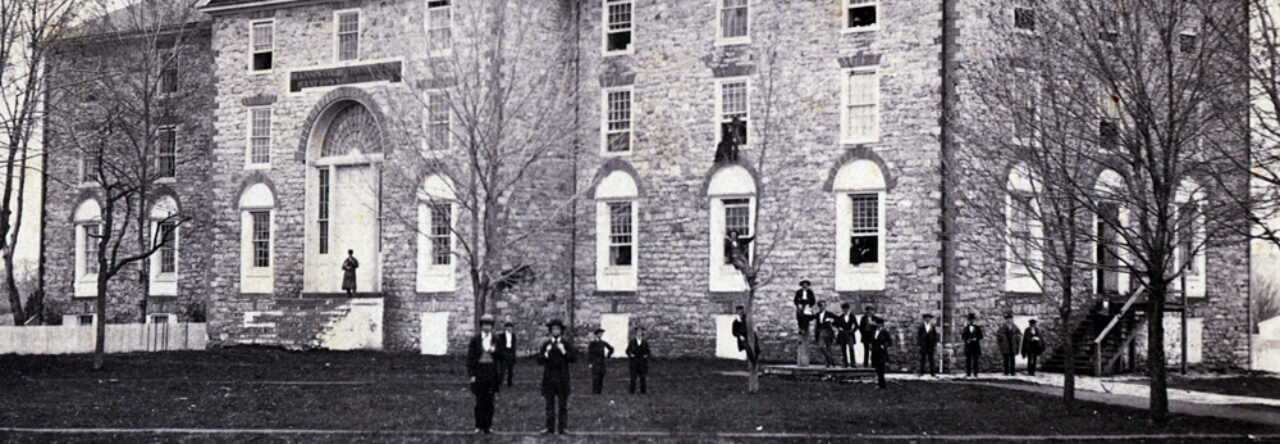

When Dickinson College President Jesse Peck arrived in Staunton, Virginia, for a conference in the spring of 1849, local authorities detained him as a result of a prank by Dickinson students. As the Richmond (VA) Examiner reported:

When Dickinson College President Jesse Peck arrived in Staunton, Virginia, for a conference in the spring of 1849, local authorities detained him as a result of a prank by Dickinson students. As the Richmond (VA) Examiner reported:

“some reprobate student…wrote a letter to the Physician of the Hospital [in Staunton], giving him a description of some individual who had left Carlisle, the seat of Dickinson College, in a state of mental derangement; and stating, furthermore, that it was more than probable that the said individual had betaken himself to Staunton, inasmuch as it was a sort of monomania with him to regard himself as the President of [Dickinson College],…. It is needles to add, that the description of the insane person coincided precisely with the appearance of the Rev. Doctor himself – and that it required the reiterated identifications of the ministers of the Conference around, to save him from confinement!”

Moncure Conway (Dickinson College Class of 1849), who later became a southern abolitionist, admitted that he was one of the student leaders involved with the prank. You can read the full story here.

The McClintock Riot took place on June 2, 1847 in Carlisle, Pennsylvania after two slave owners from Maryland arrived with plans to capture three fugitive slaves. After breaking into a house in Carlisle, the two men were arrested. Local authorities also placed the fugitive slaves in custody. The Pennsylvania legislature, however, passed a law in early March 1847 that made it illegal for state officials to help anyone trying to catch fugitive slaves. After Professor John McClintock told Judge Samuel Hepburn about the new law, Hepburn “pronounced them illegally in custody.” A riot occurred as the fugitive slaves left the courthouse. While two fugitive slaves escaped, one was forced to return to Maryland. Professor McClintock denied that he was responsible for what happened:

“All that I did was to try to do my duty to the laws of the land. But the slavecatchers have spread abroad the report that I incited the riot, and have sworn to it, and I am under bail to appear at August court.”

Several other letters and newspaper articles related to this even are also available on House Divided.

See Slideshow below

[showtime]

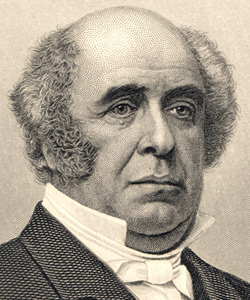

Thaddeus Stevens, one of the most powerful and controversial congressmen of the nineteenth century is the central figure of a large restoration project conducted by the Historic Preservation Trust of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Stevens was an adamant opponent of slavery and helped runaway slaves escape, even going so far as to employ spies to watch for slave-catchers. He was also a leading attorney in several fugitive slave cases, most notably the Christiana Treason Trial (1851). Stevens also shared his home with Lydia Hamilton Smith, a mixed race woman who managed his household affairs and also proved to be an enormously successful businesswoman herself.

Thaddeus Stevens, one of the most powerful and controversial congressmen of the nineteenth century is the central figure of a large restoration project conducted by the Historic Preservation Trust of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Stevens was an adamant opponent of slavery and helped runaway slaves escape, even going so far as to employ spies to watch for slave-catchers. He was also a leading attorney in several fugitive slave cases, most notably the Christiana Treason Trial (1851). Stevens also shared his home with Lydia Hamilton Smith, a mixed race woman who managed his household affairs and also proved to be an enormously successful businesswoman herself.

The Stevens & Smith Historic site is a $20 million educational and interpretive complex, integrating the restored 19th century properties of Stevens and Smith located in historic downtown Lancaster, Pennsylvania featuring an original cistern discovered in 2003 believed by historians and archeologists to have been used by Stevens and Smith as a hiding place for escaping slaves along the Underground Railroad. A cistern is an underground storage tank used for holding water.

The planning for the Stevens & Smith Historic site overcame several obstacles before its approval, specifically the original plans for a new downtown convention center in Lancaster, Pennsylvania calling for the demolition of the historic sites previously owned and managed by Stevens and Smith. The Historic Preservation Trust of Lancaster County possessed protective easements on the properties and were successful in developing a strategy for the preservation of Stevens’ Lancaster city law office and residence from the antebellum period within the new Lancaster County Convention Center.

For more information check out the Stevens & Smith Historic Site online for a full overview and updates on the project. The site also features a video on the story of Stevens & Smith and images of the proposed historical site. Fergus Bordewich’s article, “Thaddeus Stevens and James Buchanan – How Their Historic Rivalry Shaped America” is a great source for historical background on Stevens’ and Smith’s contributions and connections to the abolitionist movement in Lancaster. Further information can be found on the Thaddeus Stevens Society website including an overview of the archeological dig of the cistern conducted outside Stevens’ residence and law office. The address for the site is located at 45-47 South Queen Street Lancaster, Pennsylvania.