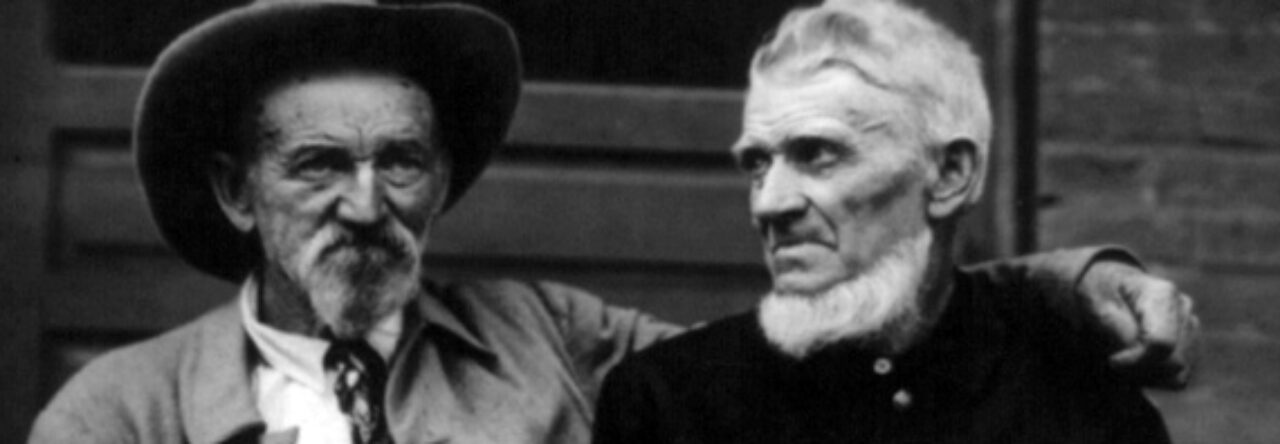

Taylor Brothers (National Park Service)

On July 2, 1863 at 5:40AM Isaac Taylor recorded in his diary that his regiment, the 1st Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment, had arrived at Gettysburg. “Order from Gen. [John] Gibbon read to us in which he says this is to be the great battle of the war & that any soldier leaving ranks without leave will be instantly put to death,” as Taylor noted. By the end of the day 215 of the 262 soldiers in the regiment had been killed or wounded. While Isaac had died, his brother, Patrick Henry Taylor, apparently made it out of the battle without injury. Patrick added the final entry to the diary, which explained that Isaac had been “killed by a shell about sunset” and was “buried…[about] a mile South of Gettysburg.”

Life & Family

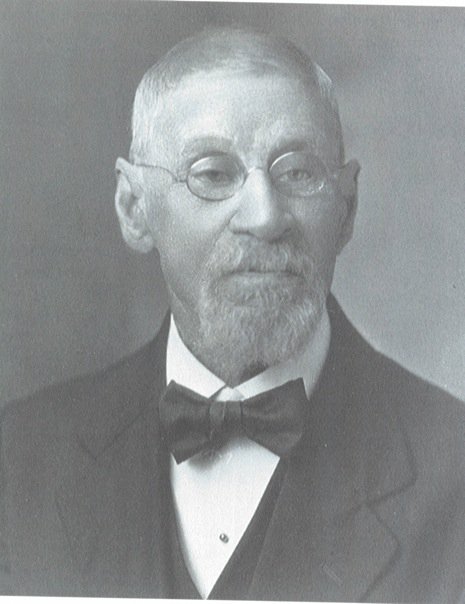

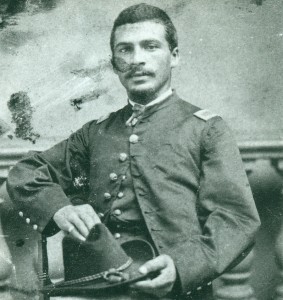

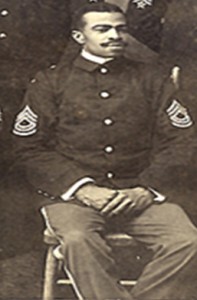

While both Isaac and Patrick Henry (family and friends called him “Henry” or “P. H.”) were born in Rowe, Massachusetts, their family moved to a farm in Fulton County, Illinois in the early 1850s. After they graduated from a school in Prairie City, Illinois, they went to Burlington University in Burlington, Iowa. Both became teachers after college – Isaac in Fulton and Henry in Morrison County, Minnesota. In 1861 Henry joined the First Minnesota in late May while Isaac followed several months later in August. Isaac’s diary covers his Civil War experience between January 1862 and his death at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. Henry also kept a diary, which was published in the Cass County Democrat in 1933. After the Civil War, Henry went back to Fulton County, Illinois to teach. In 1867 Henry moved to Missouri, when he continued to teach and work on his farm. He died in Harrisonville, Missouri on Dec 20, 1907. While it is unclear when he married, Mary Ann, Henry’s first wife ,died on May 8, 1866. Henry married Harriet R Thomas in Greenbush, Illinois, on Aug 29, 1867 and had seven children.

Isaac Taylor, whose parents were Johnathan Hastings Taylor Alvira Johnson, had twelve siblings. Four other Taylor brothers also served in the Union army during the Civil War. While Jonathan (Second Minnesota Battery of Light Artillery), Danford (Twelfth Illinois Cavalry), and Samuel (102nd Illinois Infantry) survived the war, Judson was with Company K of the Eleventh Illinois Cavalry when he died at Vicksburg on December 1, 1864.

Sources

The Minnesota History Magazine published Isaac’s Taylor’s diary in 4 sections, which you can download as PDF files: Part 1 ; Part 2 ; Part 3 ; Part 4. The Richard Moe Collection at the Minnesota Historical Society also has material related to the Taylor brothers, including obituaries, letters, a photograph of Henry and Isaac Taylor, a transcript of Patrick Henry Taylor’s diary. They apparently do not have the original copy of Isaac Taylor’s diary. As noted in Part 1 of the diary (see footnote 2 page 11), Miss Emma R. Taylor of Avon, Illinois owns other materials related to the Taylor family.

Letters and diaries about the Battle of Gettysburg written by other members of the First Minnesota are available on this page. In addition, you can read another account of the regiment’s actions in James A. Wright’s No More Gallant a Deed: a Civil War Memoir of the First Minnesota Volunteers (2001). Several historians have studied the First Minnesota Volunteer Infantry, including John Quinn Imholte’s The First Volunteers; History of the First Minnesota Volunteer Regiment, 1861-1865 (1963), Richard Moe’s Last Full Measure: The Life and Death of the First Minnesota Volunteers (1993), and Brian Leehan’s Pale Horse at Plum Run: The First Minnesota at Gettysburg (2004).

Places to Visit

The Minnesota Historical Society in St. Paul has collections that contain material on the Taylor Brothers. You can learn more about their current exhibits on this page. In addition, the First Minnesota Infantry’s monument at Gettysburg National Military Park is located at Hancock Avenue and Humphreys Avenue. See this page to learn more about the monument.

Artifacts

The Minnesota Historical Society has this First Minnesota Regimental Battle Flag that was at the Battle of Gettysburg. In addition, Private Marshall Sherman of Company Company C (First Minnesota) captured this 28th Virginia Battle Flag during Pickett’s Charge on July 3, 1863. Other items available at the Minnesota Historical Society include this Canteen, Bayonet Sheath, a Frock Coat, different kinds of drums, a kerosene army stove, and a badge from the First Minnesota reunion at Gettysburg in 1897.

Images

A photograph of Patrick H. Taylor and Issac Taylor from 1863 is available from http://www.1stminnesota.net/. While they cite the US Army Military History Institute, we are still searching their records. It does not appear to be in their digital Civil War Photograph collection. The Minnesota Historical Society’s Virtual Resources Database also has other images related to the First Minnesota, including:

“Officers of the 1st Minnesota Volunteers standing in front of the commandant’s quarters“

“Company D, 1st Minnesota Regiment posed at the southeast corner of Nicollet Avenue and First Street, Minneapolis.”

“Dedication of monument to First Minnesota Regiment at Gettysburg.” (July 2, 1897)

Survivors of the 1st Minnesota at Gettysburg. (1913)

“Reunion of 1st Minnesota Volunteers at the Minnesota Soldiers Home” (1921)