1847 || McClintock Slave Riot

John McClintock was one of Dickinson College’s most renowned professors. He began teaching Latin and Greek at Dickinson during the 1830s, a period when the school was struggling to overcome a series of major financial setbacks. McClintock helped restore the college’s reputation. Yet McClintock’s life as a scholar and beloved teacher experienced an abrupt turn on June 2, 1847, when he became embroiled in a deadly fugitive slave episode that played out in Carlisle. That afternoon, two slave catchers from Maryland were in local court trying to secure three fugitive slaves who had recently escaped from nearby Hagerstown, Maryland. McClintock later claimed he had only learned about the hearing by accident as he was taking his daily walk. The professor was well known for his opposition to slavery, but he argued that he could never condone violence or breaking the law. Yet when a riot erupted as the prisoners were being transferred, leaving one of the slave catchers fatally wounded, McClintock found himself accused of being ringleader of the violent antislavery resistance. Southern students at first angrily threatened to leave the college as McClintock was put on trial that summer, along with dozens of Carlisle’s leading black community activists, in a showdown that captured national attention. The college professor was ultimately acquitted but 11 black men were convicted and sentenced to hard labor at the state penitentiary. McClintock worked earnestly to help appeal their convictions, which the state supreme court eventually did overturn. While he was in prison, one of the convicted men claimed privately that he could have implicated McClintock in their crime but that he “would rather hang than do it.” Was the quiet scholar more involved in the resistance effort than he was willing to admit? We might never know for sure. Not long after the 1847 riot, McClintock left Dickinson to become editor of the Methodist Quarterly Review. He later served as a minister in New York and Paris before becoming a university president in New Jersey. During those years, he became a friend of Abraham Lincoln’s and a prominent Unionist, but never commented further on his role in the fugitive slave episode. However, when McClintock died in 1870 a group of black residents in Carlisle, celebrating ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, which granted black men the right to vote, gratefully carried a revealing banner that read: IN MEMORY OF DR. McCLINTOCK, PERSECUTED FOR OUR SAKE.”

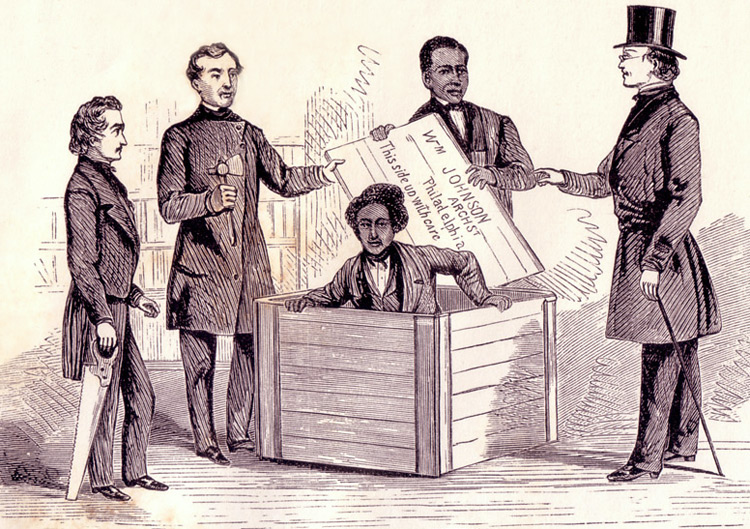

1849 || Henry “Box” Brown escapes from slavery

In March 1849, a man named Henry Brown traveled from Richmond to Philadelphia in a most unusual way. Brown, a Virginia slave distraught because his enslaved wife and children had just been sold away from him, made a series of secret arrangements to escape to freedom. The help of some brave friends, a wide network of antislavery allies, and a new shipping service advertised by the Adams Express Company made his daring operation possible. Brown planned to hide inside a box until he was safely delivered to the Anti-Slavery office in Philadelphia. The journey itself took just over 24 hours, by wagon, train, and boat. Everyone involved knew the risks, but the heartbroken husband and father insisted on making the desperate effort to flee from enslavement. Henry “Box” Brown enjoyed his miraculous “resurrection” in Philadelphia on March 24, 1849, in the presence of some leading Underground Railroad or vigilance agents from the North. Two of those men were associated with Dickinson College, most notably, James Miller McKim (Class of 1828), head of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and the escape’s main northern organizer. Charles Dexter Cleveland, a former Dickinson professor, was also present. Nobody from Pennsylvania went to jail for assisting in what became the most celebrated (and notorious) escape for the period, but the sensational episode contributed mightily to Southern calls for a tougher federal fugitive slave law. Henry Brown never reunited with his family but he was never recaptured. He lived as a free man in the United States, England and Canada until his death in 1897.

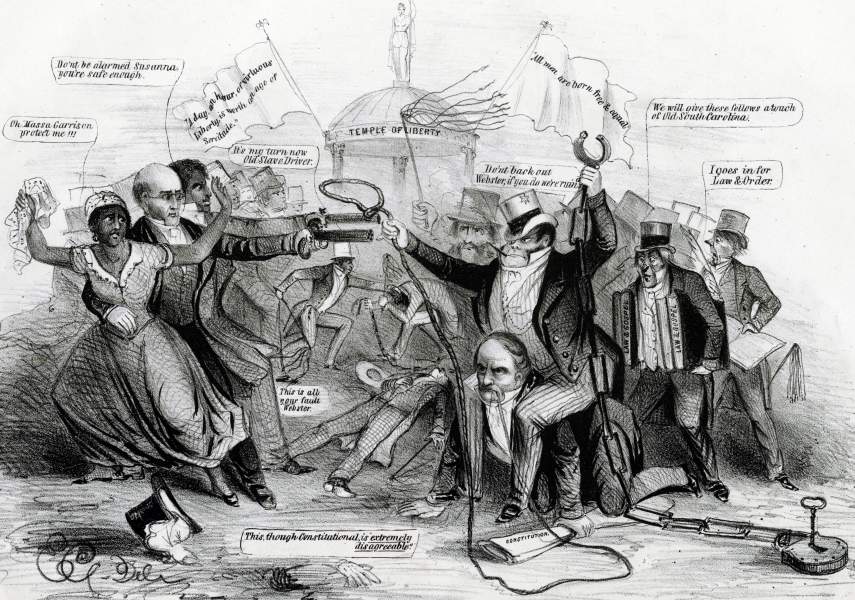

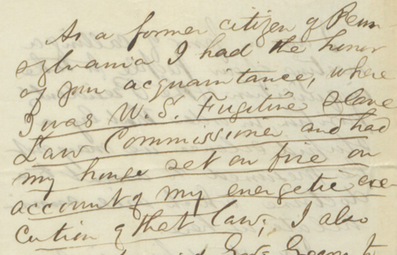

1853 || McAllister Quits as Fugitive Commissioner

The Compromise of 1850 included several measures designed to quell the rising tensions between slave states and free states. The most important of these measures –and certainly the most controversial– was a new, tougher federal Fugitive Slave Law (September 18, 1850). The heavily-criticized statute authorized commissioners of the U.S. Circuit Court in Northern states and territories to take extreme steps in order to help secure and return any runaway slaves from the nation’s fifteen Southern slave states. Perhaps the most notorious of these “fugitive slave commissioners” was a Harrisburg attorney named Richard McAllister, who was a graduate of Dickinson College (Class of 1840). McAllister presided over fugitive slave rendition hearings out of his office in Harrisburg for less than three years (September 1850 to May 1853), but in that short time span he apparently sent back more men, women and children into slavery than any other U.S. commissioner across the entire country over the full fourteen-year period of the law’s existence (1850-1864). McAllister was not only prolific in terms of case management, but also especially demeaning in the way he treated the black families who appeared in his hearing room, and the attorneys who represented them (including some fellow Dickinsonians, like anti-slavery attorney Mordecai McKinney). McAllister’s aggressive approach provoked a bitter reaction around Pennsylvania. He became ostracized from his church, was driven into debt and even had his house set on fire before finally resigning from office in disgust in May 1853. McAllister later moved out West and served in the Union army during the Civil War. He eventually settled in Washington, DC and worked as an attorney until his death in 1887.

1857 || Dred Scott Case and Dickinsonians

In 1846, Dred and Harriet Scott, an enslaved couple living with their two daughters in St. Louis, Missouri, filed separate freedom suits in state circuit court claiming they had been held illegally as slaves in free states and territories. They lost the first round on a technicality, but won a later round. In 1852, however, the Missouri Supreme Court overturned their freedom suit victory and threw out decades of precedent favoring the “once free, always free” doctrine of interstate comity. The state’s chief justice noted pointedly, “Times now are not as they were.” Dred Scott then took their case into federal court, and eventually the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against him in Scott v. Sandford (1857). It was Chief Justice Roger Taney who announced the court’s sweeping 7-2 opinion against Scott on March 6, 1857. Taney’s opinion for the majority ruled that blacks could not be considered U.S. citizens, that southern states did not have to honor northern laws regarding returned slaves; and that Missouri Compromise of 1820 had itself been unconstitutional because Congress lacked the authority to restrict slavery in the territories. He was joined in this verdict by fellow Dickinsonian, Robert C. Grier. Associate Justice Grier also took it upon himself during the final tense days of the court’s deliberations to keep another Dickinson alum, President-elect James Buchanan, aware of the secret discussions. When the final verdict was announced in March 1857, there were two dissenting justices. One of them, John McLean of Ohio, also had Dickinson connections. He had been a member of the college’s board of trustees for over two decades, from 1833 to 1855. Despite losing, Dred Scott and his family received their freedom in the spring of 1857. Taylor Blow, son of Scott’s first owner and a resident of St. Louis, actually purchased and then manumitted the entire family. Dred Scott died the next year, a free man. His wife and daughters, however, survived the Civil War. Some of their descendants are still alive today.

1860 || Duncan identified as leading slaveholder

On the eve of the Civil War, Stephen Duncan (Class of 1805) was identified in the U.S. census as the nation’s second largest slaveholder. In 1860, Duncan owned 2,241 slaves, a massive workforce worth about $1.7 million. However, if one adds up all of the enslaved people bought and sold by the prominent Mississippi planter and banker over the course of his lifetime, it is possible that he owned more human beings than any other individual in American history. Although Duncan was residing at one of his massive Mississippi plantations in 1860, he began his life in the North, as part of a slaveholding family in Carlisle. He graduated from Dickinson in 1805 and not long after settled in Mississippi on some Duncan family-owned investment property near Natchez. He soon became quite influential, amassing a fortune in land and slaves, while developing into an aggressive banker as well as a notably reform-minded planter. Despite owning thousands of slaves, Duncan viewed himself as a moderate on the issue. In 1831, he formulated a plan to end the institution by using tariff revenues to purchase slaves and transport them outside the country. “A century or more would be required for the extinguishment of slavery,” Duncan predicted. He became an influential Mississippi backer of the American Colonization Society, which promoted the removal of freed American blacks to Liberia, a colonial settlement in West Africa. Duncan generally tried to avoid politics, but when the secession crisis engulfed the South during the winter of 1860-61, he positioned himself as a slaveholding unionist. Then during the war itself, he and his family actually lobbied the Lincoln Administration privately for help in keeping their plantations –and their enslaved labor. Daughter-in-law Mary Duncan complained directly by letter to President Lincoln. “It seems rather hard… that—as recognized Unionists—we should be made to suffer so peculiarly,” she wrote in May 1863. According to her, invading Union forces had confiscated “books, curtains & all they wanted” and “forcibly seized & impressed our remaining male negroes” as laborers and soldiers. “Millions would hardly cover our losses,” she wrote, pleading “due protection for the fragment that remains of a once princely fortune.” Duncan repeated a similar line of argument later that summer. “I have no cause of complaint against President Lincoln’s Proclamation as a War Measure,” he wrote in August about the administration’s emancipation policy, “but I think there is just ground of complaint against the indiscriminate application” to loyal citizens such as himself. Finally, late in 1863, Duncan gave up arguing and abandoned his holdings in Natchez in order to escape into the North. He spent the final two years of the war in New York City. He died in 1867, still reasonably wealthy, but without any more holdings in human property.

Sources: Details from 1860 U.S. census analyzed in Martha Jane Brazy, An American Planter: Stephen Duncan of Antebellum Natchez and New York, (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2006), 150; Stephen Duncan to Mary Duncan, August 25, 1863, Series 1, General Correspondence, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, [WEB]; James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865,(New York: W.W. Norton, 2013), 138-140; Mary Duncan to Abraham Lincoln, May 24, 1863, Series 1, General Correspondence, Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, [WEB]; Brazy, An American Planter, 154-158.

1861 || Outbreak of Civil War

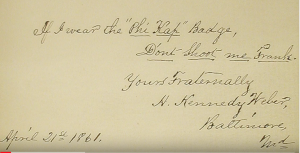

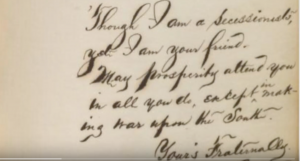

The outbreak of war was especially challenging for Dickinson College. “We lost about one half our students at a stroke,” college president Herman Johnson later admitted in 1863. The reason the students were leaving, of course, was to fight. But what made Dickinson unique was that the student body was divided in its loyalties over the slavery conflict and many realized right away that they would be fighting each other. “If I wear the Phi Kap badge, don’t shoot me Frank.” That was the way Dickinson College student Howard Weber signed the autograph book of his fraternity brother, Frank Sellers, at the very outset of the Civil War. Weber was from the slaveholding state of Maryland. Sellers was from the free state of Pennsylvania. It was late at night on Sunday, April 21, 1861, just one week after Union forces had surrendered at Fort Sumter in South Carolina. The two young men were crammed together inside Frank’s college room in Carlisle with about two dozen other members of their secret fraternity chapter. All were trying to decide what to do next. Stay in school or join the army? And if so, which army, Union or Confederate? Many of these young men were Southerners, some even from South Carolina. President Lincoln had already called for 75,000 volunteers, but days before some of those men had been attacked while traveling through nearby Baltimore, Maryland. The state of Virginia announced it was planning to leave the Union as well. The reaction in Carlisle was nearly pandemonium. One student reported to his father that the small town was “thronged” with military companies. Local residents were starting to harass Southern students. Townspeople raised Union flags over many buildings, including on the college campus. Rumors flew that locals had even approached the Dickinson president demanding that Southern students either take an oath of allegiance or leave town. Students petitioned the faculty to suspend their semester. The Phi Kap brothers who met together late on Sunday night were fully expecting their college to close. So that night, they wrote farewell notes to each other. Some were quite poignant. One student even admitted in his journal that he had cried. But others were more playful and seemed eager to experience what they imagined as the adventures of combat. It’s hard to know exactly what Howard Weber was thinking when he urged his Northern friend not to shoot him. Weber’s father was a top Democrat in Maryland who opposed Abraham Lincoln, but considered secession to be a form of treason. He had been in Baltimore during the riots against the troops and worried about his son. So, Howard Weber went home, and not into the Confederate army. He remained in Maryland until 1863, when he was forced to register for the Union draft. Then something unexpected happened. President Lincoln named his uncle, also a leading Democrat, to an important but essentially safe military position in Springfield, Illinois. Howard Weber then went out west, served under his uncle, and even became an ardent supporter of Lincoln’s. He lived the rest of his life in Springfield, where he became a prominent local bank president. Not everyone who crowded into the Phi Kappa Sigma room that night in April 1861 was so lucky. Nineteen fraternity brothers wound up fighting for the Confederacy. Fifteen served in the Union military. Many of them experienced terrible hardships, and at least four did not survive the conflict. Dickinson College remained open throughout the Civil War, but the school struggled mightily and was even briefly occupied by Confederate troops in June 1863. Nobody could have predicted any of it back in April 1861.

For more details on Dickinson College president Herman Merrills Johnson and his family, especially his wife Lucena (who wrote to President Lincoln during the war) and his daughter Mary, who later became a famous novelist, see Rachel Morgan’s web project: Mary Dillon’s Carlisle.

.

Sources: Herman Johnson to Simon Cameron, December 15, 1863, Box 2, Cameron Family Papers, MG 500, Historical Society of Dauphin County.