The Baird-McClintock student residence hall at Dickinson is named (in part) for John McClintock, a noted nineteenth-century faculty member who became embroiled in a fugitive slave crisis in Carlisle in 1847. McClintock, who was a leading Methodist public intellectual and later a college president at Drew University, has also been featured within various college publications and websites over the years.

The Baird-McClintock student residence hall at Dickinson is named (in part) for John McClintock, a noted nineteenth-century faculty member who became embroiled in a fugitive slave crisis in Carlisle in 1847. McClintock, who was a leading Methodist public intellectual and later a college president at Drew University, has also been featured within various college publications and websites over the years.

BRIEF PROFILE

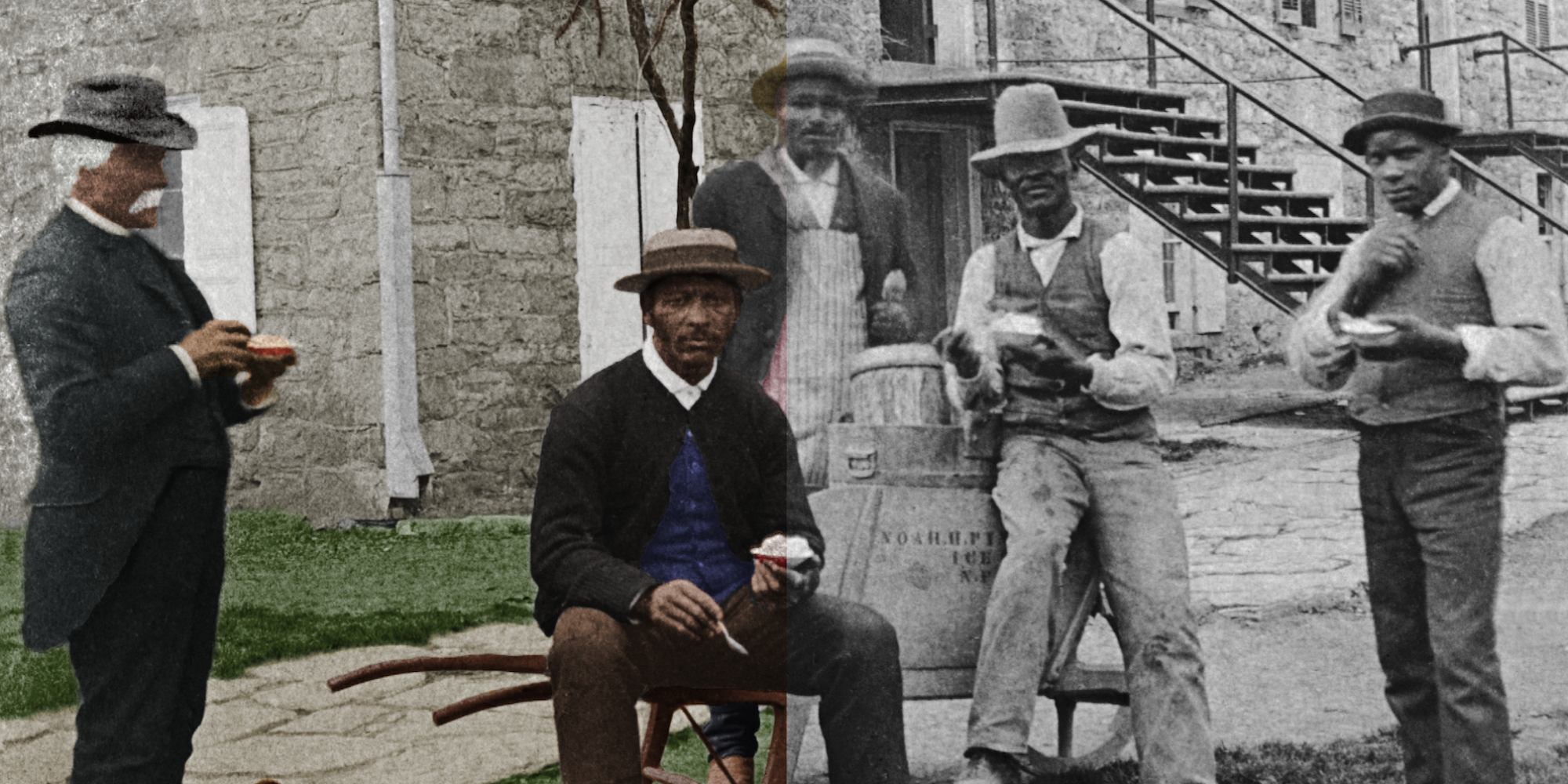

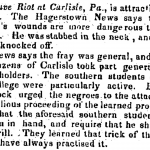

John McClintock was one of Dickinson College’s most renowned professors. At one point, the noted Methodist scholar also found himself right in the middle of the nation’s heated crisis over slavery. McClintock began teaching Latin and Greek at Dickinson during the 1830s, a period when the school was struggling to overcome a series of major financial setbacks. He helped restore the college’s reputation as one of the young nation’s foremost institutions of higher education. Yet McClintock’s life as a scholar and beloved teacher experienced an abrupt turn on June 2, 1847, when he became embroiled in a deadly fugitive slave episode that played out in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. That afternoon, two slave catchers from Maryland were in local court trying to secure three fugitive slaves who had recently escaped from nearby Hagerstown, Maryland. McClintock later claimed he had only learned about the hearing by accident as he was taking his daily walk. The professor was well known for his opposition to slavery, but he argued that he could never condone violence or breaking the law. Yet when a riot erupted as the prisoners were being transferred, leaving one of the slave catchers fatally wounded, McClintock found himself accused of being ringleader of the violent antislavery resistance. Southern students angrily threatened to leave the college as McClintock was put on trial that summer, along with dozens of Carlisle’s leading black community activists, in a showdown that captured national attention. The college professor was ultimately acquitted but 11 black men were convicted and sentenced to solitary confinement at the state penitentiary. McClintock worked earnestly to help appeal their convictions, which the state supreme court eventually did overturn. While he was in prison, one of the convicted men claimed privately that he could have implicated McClintock in their crime but that he “would rather hang than do it.” Was the quiet scholar more involved in the resistance effort than he was willing to admit? We might never know for sure. Not long after the 1847 riot, McClintock left Dickinson to become editor of the Methodist Quarterly Review. He later served as a minister in New York and Paris before becoming a university president in New Jersey. During those years, he became a friend of Abraham Lincoln’s and a prominent Unionist, but never commented further on his role in the fugitive slave episode. However, when McClintock died in 1870 a group of black residents in Carlisle, celebrating ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, which granted black men the right to vote, gratefully carried a revealing banner that read: IN MEMORY OF DR. McCLINTOCK, PERSECUTED FOR OUR SAKE.”

Video produced by Frank Kline (Class of 2019)

FURTHER READING

- Dickinson College encyclopedia: John McClintock (1814-1870)

- House Divided research engine: McClintock, John

- Crooks, George R. Life and Letters of the Rev. John M’Clintock. New York: Nelson & Philips, 1876 [WEB]

- Houpt, Lindsay. “Fugitive Slave Cases in Cumberland County, PA,” Cumberland County History 27 (2010): 69-77 [WEB]

- Slotten, Martha C. “The McClintock Slave Riot of 1847,” Cumberland County History 17 (2000): 14-33 [WEB]

IMAGE GALLERY

All images courtesy of the House Divided Project at Dickinson College with original publication details available inside our research engine