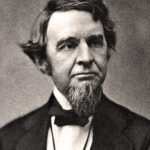

Outside of a recent installation on a famous fugitive slave escape at the House Divided studio, there is no building, statue or portrait dedicated to the memory of James Miller McKim on the campus of Dickinson College. Yet he was arguably one of the nation’s most important abolitionists, an influential nineteenth-century anti-slavery leader not only in Pennsylvania, but also across the nation. McKim was also a major figure during the Civil War itself and later during Reconstruction, fighting repeatedly for emancipation, civil rights, and national unity.

Outside of a recent installation on a famous fugitive slave escape at the House Divided studio, there is no building, statue or portrait dedicated to the memory of James Miller McKim on the campus of Dickinson College. Yet he was arguably one of the nation’s most important abolitionists, an influential nineteenth-century anti-slavery leader not only in Pennsylvania, but also across the nation. McKim was also a major figure during the Civil War itself and later during Reconstruction, fighting repeatedly for emancipation, civil rights, and national unity.

BRIEF PROFILE

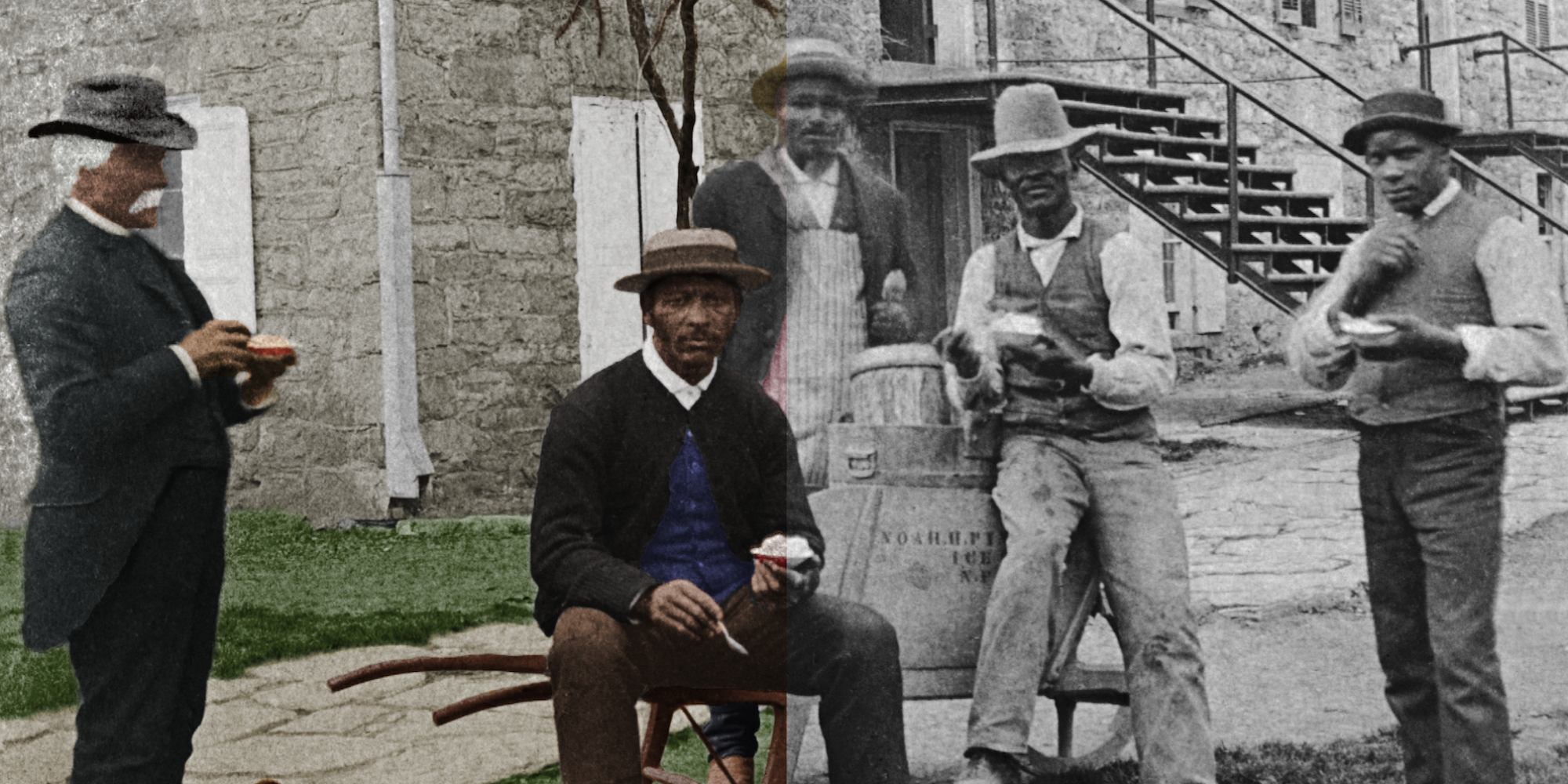

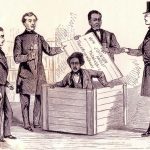

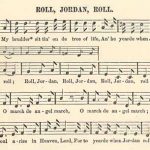

James Miller McKim, a graduate of Dickinson College, was one of the great civil rights advocates of the nineteenth century. He grew up in rural Pennsylvania at a time when the state was gradually abolishing slavery within its own borders. But in the early 1830s, as a young Presbyterian minister, McKim became a committed abolitionist –an impassioned opponent of Southern slavery– after reading fiery pamphlets by journalist William Lloyd Garrison. McKim encountered Garrison’s radical views while visiting his barber, a local black leader, who helped tutor him in the antislavery cause. McKim soon joined the Garrisonian abolitionist movement, becoming close friends with figures such as Quaker feminist Lucretia Mott and with Theodore Weld, the organizer of a controversial band of abolitionist orators who traveled the North speaking out against slavery. McKim eventually settled in Philadelphia where he came to lead the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and helped to organize Underground Railroad efforts, assisting runaway slaves in their dangerous escapes to freedom. McKim was at the center of the most famous escape of the era, the secret journey of Henry “Box” Brown from Richmond to Philadelphia in 1849, while Brown was hidden for over 24 hours inside of a shipping crate. Over the course of the 1850s, McKim, along with noted black abolitionist William Still, and other members of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee aided in several hundred other documented and successful escapes. McKim was also involved in John Brown’s 1859 raid at Harpers Ferry. He did not participate directly in Brown’s brief war against slaveholders, but McKim openly praised the abolitionist zealot and traveled with his wife Mary after Brown’s execution to help recover his body for burial. McKim also seemed to welcome the outbreak of Civil War in 1861. He reasoned that “a virtuous war” was “better than a corrupt peace” and worked from the very beginning of the conflict to ensure that it was about emancipation of the slaves and promoting equal opportunities for the freed people. McKim took a personal interest in recruiting black soldiers for the Union army and in coordinating relief efforts for liberated families. In 1862, he traveled to Union-occupied South Carolina, even bringing along his daughter Lucy, who became well-known herself for collecting and transposing slave songs and spirituals for publication. During the final years of the war, McKim became a leading abolitionist supporter of President Lincoln and lobbied Congress successfully for the creation of a new federal agency for freed people. Following the Civil War, McKim also helped lead the effort to desegregate Philadelphia street cars and to launch a leading progressive periodical, The Nation, which is still being published today. James Miller McKim died in 1874, after spending decades advocating for the human and civil rights of African Americans.

Video produced by Becca Stout (Class of 2019)

FURTHER READING

- Dickinson College encyclopedia: James Miller McKim (1810-1874)

- House Divided research engine: McKim, James

- Cohen, William. “James Miller McKim: Pennsylvania Abolitionist,” PhD dissertation, New York University, 1968. [PDF]

- Rebecca Stout, “James Miller McKim and Civil War Abolitionism,” Honors Project, Dickinson College, 2018-19 [WEB]

IMAGE GALLERY

All images courtesy of the House Divided Project at Dickinson College (except where noted) with original publication details available inside our research engine

PRIMARY SOURCES

- Speech of J. Miller McKim on 30th Anniversary of American Anti-Slavery Society (from The Liberator, December 25, 1863) [PDF]