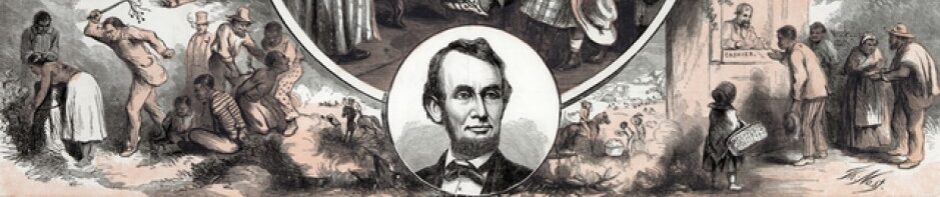

The story of how runaway slaves helped launch the movement toward wartime emancipation in spring 1861 is becoming better known, yet it remains one that is typically not featured in history textbooks or classrooms. However, students and teachers can find numerous resources online to help explain this fascinating tale of ordinary people fighting for their own freedom. The main question for students revolves around a hotly debated judgment call that has divided modern scholars –to what degree did slaves help free themselves during the Civil War?.

The story of how runaway slaves helped launch the movement toward wartime emancipation in spring 1861 is becoming better known, yet it remains one that is typically not featured in history textbooks or classrooms. However, students and teachers can find numerous resources online to help explain this fascinating tale of ordinary people fighting for their own freedom. The main question for students revolves around a hotly debated judgment call that has divided modern scholars –to what degree did slaves help free themselves during the Civil War?.

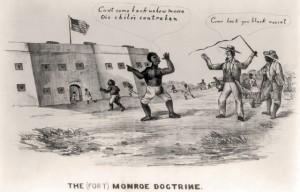

Adam Goodheart has an excellent piece adapted from his book 1861 and available online from the New York Times magazine that details the story of three Virginia slaves –Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory and James Townsend– who rowed across the James River on May 23, 1861 and presented themselves to Union army officials at Fort Monroe near Norfolk, setting in motion a chain of events that led General Benjamin Butler to get approval from the War Department effectively declaring these men as “contraband of war” and preventing them from being returned to their Confederate army masters. You can read Butler’s first dispatch on the subject (May 24, 1861) and the encouraging response from the War Department (May 30, 1861), which tentatively authorized the contraband policy. See also a more complete authorization from Secretary of War Simon Cameron on August 8, 1861. If you want to review dozens of such Union Army’s documents on contrabands, simply consult the War of the Rebellion: Official Records (OR), Series II, Volume 1, “Prisoners of War, Etc.,” available online in several places, including from the Making of America / Cornell. But note that Butler himself did not use the phrase “contraband of war” at least in writing until July 30, 1861, in a letter to Secretary of War Simon Cameron. By then, the phrase had already been popularized in the northern press, though historian James Oakes suggests that it was Butler who had first promoted the idea of “contrabands” in his conversations with reporters.

Goodheart’s work helped launch the New York Times blog series, “Disunion,” a first-rate resource for students and teachers that’s much easier to digest than the OR. See especially posts by these contributors on emancipation-related topics: Gregory P. Downs, Steven Hahn, Taft Kiser, and William G. Thomas. These brief essays provide a better sense of how freedom began to happen during the first year of the war –long before the actual Emancipation Proclamation. Disunion posts are especially helpful for providing memorable details about often-obscure figures. There is also one particularly useful piece from the Disunion series that helps summarize recent debates among scholars on the emancipation issue, provocatively entitled, “Was Freedom Enough?” It is also worth noting that there is an independent but well-written blog series from historian Donald R. Shaffer called “Civil War Emancipation” that is entirely devoted to these issues and particularly good about highlighting online primary sources. See also this useful post from Jared Frederick at the “History Matters” blog which details historian Gary Gallagher’s claim that the Union army itself deserves more credit for spreading freedom.

One of the best educational resources for the general debate over how much slaves helped free themselves comes from an Annenberg Learner workshop available here. Free materials include primary source document sets, historic images, background information, and lesson plan ideas. But the most dynamic new portrait of the unfolding wartime freedom process comes from the University of Richmond’s “Visualizing Emancipation” animated map, which currently documents more than 3,000 specific emancipation “events” occurring between 1861 and 1865, mostly relying on records from the OR series.