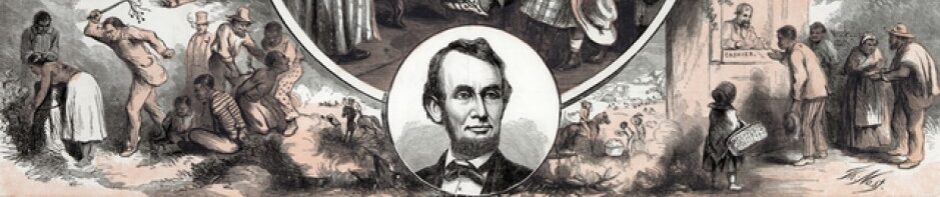

During the Civil War, Republicans in the 37th Congress managed to navigate two major pieces of legislation through Capitol Hill that helped free certain types of Confederate slaves. These “confiscation” acts have since become mostly forgotten, however, because their impact on the struggle to abolish slavery was overwhelmed by Lincoln’s emancipation policy. Nonetheless, those acts remained in force throughout the war and arguably triggered Lincoln’s pivotal decision to emancipate slaves by military decree beginning on January 1, 1863.

The First Confiscation Act (August 6, 1861) was not an explicit freedom statute, but it authorized Union army officials to seize any slaves employed by the Confederate army. The fourth section of the statute read:

“That whenever hereafter, during the present insurrection against the Government of the United States, any person claimed to be held to labor or service under the law of any State, shall be required or permitted by the person to whom such labor or service is claimed to be due, or by the lawful agent of such person, to take up arms against the United States, or shall be required or permitted by the person to whom such labor or service is claimed to be due, or his lawful agent, to work or to be employed in or upon any fort, navy yard, dock, armory, ship, entrenchment, or in any military or naval service whatsoever, against the Government and lawful authority of the United States, then, and in every such case, the person to whom such labor or service is claimed to be due shall forfeit his claim to such labor, any law of the State or of the United States to the contrary notwithstanding. And whenever thereafter the person claiming such labor or service shall seek to enforce his claim, it shall be a full and sufficient answer to such claim that the person whose service or labor is claimed had been employed in hostile service against the Government of the United States, contrary to the provisions of this act.”

Although the First Confiscation Act was not an explicit freedom statute, by neither attempting to define the legal status of the “forfeited” slaves, nor by fully addressing the concerns of the so-called contrabands, it nonetheless had the effect of increasing the spread of freedom almost immediately because of instructions from Secretary of War Simon Cameron (August 8, 1861) that directed army officers to receive and protect fugitives from both disloyal and loyal masters, suggesting that it was the only practical way to proceed and that Congress would ultimately have to figure out a way to provide “just compensation to loyal masters.”

Cameron’s instructions were not uniformly followed, however, and a number of Union officers continued to return fugitive slaves or to deny runaways protection. Over the next several months, this situation provoked repeated clashes between Republican politicians and certain Union generals over what the law required and what military necessity demanded. One notable exchange occurred between Secretary of State William Seward and General George B. McClellan in December 1861. Arguments such as these eventually provoked the Congress to debate and pass a Second Confiscation Act (July 17, 1862), which went far beyond the first statute in declaring confiscation as punishment for treason and in labeling Confederate slaves as “captives of war” who were to be “forever free.” The Congress also extended their confiscation policy to include any slaves employed by disloyal master anywhere –not just those employed by the rebel armies or navies. The key section of the statute regarding emancipation was Section 9:

“That all slaves of persons who shall hereafter be engaged in rebellion against the government of the United States, or who shall in any way give aid or comfort thereto, escaping from such persons and taking refuge within the lines of the army; and all slaves captured from such persons or deserted by them and coming under the control of the government of the United States; and all slaves of such person found on [or] being within any place occupied by rebel forces and afterwards occupied by the forces of the United States, shall be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves.”

Abraham Lincoln signed the new confiscation statute on Thursday, July 17, 1862, but did so reluctantly, convinced that it was both unconstitutional and impractical. He actually drafted a veto message earlier that week, but after some last-minute negotiations, the president and Congress managed to avoid a dramatic confrontation. Nonetheless, President Lincoln issued his veto message with his signature (something that today is called a presidential signing statement) and proceeded to make plans to supersede congressional confiscation with his own emancipation policy, presented in its first draft form to his Cabinet on Tuesday, July 22, 1862.

Congressional confiscation policy had many “authors” and provoked numerous arguments in House and Senate debates. No figure, however, was more important to the development of the policy than Senator Lyman Trumbull, a Republican from Illinois, who chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee. Under these circumstances, he might also be considered a “Great Emancipator” from Illinois. You can browse or search the congressional confiscation debates online through “A Century of Lawmaking,” a massive collection of congressional documents courtesy of the Library of Congress.