Historian James Oakes argues that there was a “federal consensus” about slavery in the years between 1787 and 1861 that has too often been overlooked in examinations of emancipation’s origins. Oakes believes that a careful reading of some important primary sources helps reveal that antebellum Americans –including most abolitionists and pro-slavery defenders– generally accepted as constitutional truth that the federal government could not abolish slavery in states where it already existed. Documents such as the 1833 “Declaration of Sentiments” from the American Anti-Slavery Society illustrate this point. Even these ardent Garrisonian abolitionists noted in their initial organizational mission statement that “We fully and unanimously recognize the sovereignty of each State, to legislate exclusively on the subject of Slavery, which is tolerated within its limits,” adding further in terms that fully acknowledged what modern-day students might call states’ rights, that “we concede that Congress under the present national compact [emphasis in original], has no right to interfere with any of the slave States, in relation to this momentous subject.”

Historian James Oakes argues that there was a “federal consensus” about slavery in the years between 1787 and 1861 that has too often been overlooked in examinations of emancipation’s origins. Oakes believes that a careful reading of some important primary sources helps reveal that antebellum Americans –including most abolitionists and pro-slavery defenders– generally accepted as constitutional truth that the federal government could not abolish slavery in states where it already existed. Documents such as the 1833 “Declaration of Sentiments” from the American Anti-Slavery Society illustrate this point. Even these ardent Garrisonian abolitionists noted in their initial organizational mission statement that “We fully and unanimously recognize the sovereignty of each State, to legislate exclusively on the subject of Slavery, which is tolerated within its limits,” adding further in terms that fully acknowledged what modern-day students might call states’ rights, that “we concede that Congress under the present national compact [emphasis in original], has no right to interfere with any of the slave States, in relation to this momentous subject.”

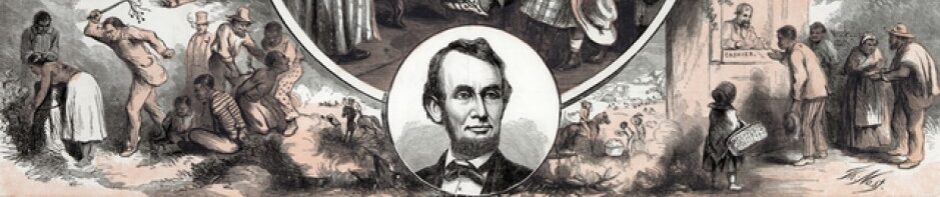

This was exactly the point which Abraham Lincoln acknowledged in his First Inaugural Address on March 4, 1861. He began by quoting himself, from the first Lincoln-Douglas Debates at Ottawa in 1858: “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” Then he quoted from the 1860 Republican Party platform: “Resolved, That the maintenance inviolate of the rights of the States, and especially the right of each State to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively, is essential to that balance of power on which the perfection and endurance of our political fabric depend; and we denounce the lawless invasion by armed force of the soil of any State or Territory, no matter what pretext, as among the gravest of crimes.”

Study Questions

1. If most abolitionists and Republicans conceded that slave states had to abolish slavery by their own actions, then why did many white southerners perceive them as such a threat to the southern way of life?

2. What types of actions against the peculiar institution did antislavery activists urge upon the federal government if not measures designed to force southerners into abandoning slavery directly?

Further Research

1. Can you find other examples of this “federal consensus” in letters, diaries, speeches, newspaper accounts or other primary sources from the era? Where and how might you look for such sources?

2. Oakes acknowledges in his work that not everyone accepted this antebellum consensus about states’ rights and the fate of slavery, but can you or your students identify such views in the primary source evidence and then attempt to categorize them?

The Federal Consensus was first brought up by James Madison in the early part of Februrary 1790.