In what was arguably the best-known speech of the antebellum era, Senator Daniel Webster (Whig, Mass.) provided a stirring attack on extreme southern states’ rights in his “Second Reply to Hayne,” delivered on the Senate floor, January 26-27, 1830, in response to Robert Y. Hayne, a Democrat from South Carolina during a debate about federal land policy. Webster argued that no state could “interfere” with federal legislation because the national government was supreme. He claimed that the emerging (and extreme) states’ rights position “leads us to inquire into the origin of this government and the source of its power. Whose agent is it?” he asked. “Is it the creature of the State legislatures, or the creature of the people?” Webster quickly provided his answer.

It is, Sir, the people’s Constitution, the people’s government, made for the people, made by the people, and answerable to the people. The people of the United States have declared that the Constitution shall be the supreme law. We must either admit the proposition, or dispute their authority.

The ringing conclusion to Webster’s speech was then repeated by American schoolchildren for generations: “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!”

Yet only twenty years later, a new generation of northerners, embodied by fellow Whig Senator William Seward of New York, proved more skeptical about the compatibility of those core American values. During the contentious debates over the proposed Compromise of 1850, Seward argued in his maiden speech in the Senate that there was “a higher law than the Constitution” which demanded respect for the natural rights of man. The Constitution might allow states to regulate slavery for themselves, but according to Seward there was NOTHING in the document that legitimated slave-holding. “I deny that the Constitution recognizes property in man,” he stated emphatically.

Charles Sumner, the man who succeeded Daniel Webster as senator from Massachusetts, went even further than Seward in arguing for a Constitution that treated slavery as a creature of local laws and opposed by the principles of national freedom. In an 1852 speech, titled “Freedom National, Slavery Sectional,” Sumner claimed that the Fugitive Slave Law was unconstitutional and that Congress should –and could– do everything in its power to align federal power against slavery in the territories and anywhere the institution encroached on American society outside the southern states themselves.

Study Questions

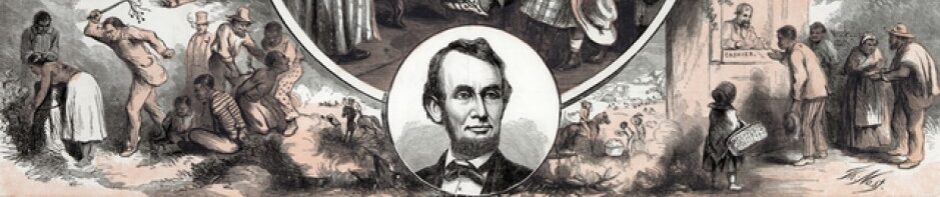

1. By closing the Gettysburg Address with a paraphrase from Daniel Webster’s famous 1830 reply to Hayne what was Abraham Lincoln trying to accomplish?

2. How could antislavery politicians such as Seward and Sumner speak out so vigorously against the evils of slavery and yet still concede that southerners could keep slavery within their own states?

Further Research

1. Search digital resources such as the House Divided research engine, Google Books, or any leading database of nineteenth-century newspapers and see how various figures have used quotations from Webster’s, Seward’s or Sumner’s most famous speeches.

2. Webster, Seward, and Sumner were leading nineteenth-century U.S. senators. Relying on information from the Senate Historical Office or other secondary sources, compare and contrast the Senate in their day with the rules and culture of the present institution.