Advanced Organizer Lesson Plan Format

|

Name: |

Paul Kim |

Date: |

7-28-06 |

Course: |

U.S. History |

||||

|

Master Teacher: |

|

Phone: |

|

Grade: |

11 |

||||

|

School: |

Chinese Christian Schools |

||||||||

Preparation to Teach

|

State Standard: |

CA 11.3.1 – Describe the contributions of various religious groups to American civic principles and social reform movements (e.g., civil and human rights, individual responsibility and the work ethic, antimonarchy and self-rule, worker protection, family-centered communities). |

|

Lesson Objective: |

Given the students’ prior understanding of notable conductors on the UR such as Harriet Tubman, they will explore the lives of two men, Levi Coffin and Chun Ki-Won, and describe the role of faith and early traumatic experience in explaining their willingness to help fugitive runaways. The students will observe themes from the UR (formation of a network of collaborators, the moral imperative to disobey state law, etc) in 19th century America being repeated on the China/North Korea border today. |

|

Materials: |

1. Primary Document: Reminiscences of Levi Coffin 2. Book Excerpt: Bound for Canaan (Ch. 4) 3. Film Documentary: Seoul Train 4. Newspaper Article: “Leading His Flock of Refugees to Asylum,” Valerie Reitman (L.A. Times) |

Instructional Plan

|

Anticipatory Set |

|

||

|

Instructional Strategy: |

Starter Question: Why would a person take great personal risk to help someone in need, even if he had nothing to gain from doing so? |

Rationale: |

|

|

Student Activity and Grouping: |

Open discussion |

Developmental needs: |

|

|

|

|||

|

Progress Monitoring: |

Solicit responses from several students, ask for specific examples they have seen or experienced. |

||

|

Presentation of an Organizer of Lesson’s Content: |

||

|

Instructional Strategy: |

Chart: A comparison of Levi Coffin and Chun Ki-Won (see below for background info on Chun).

|

Rationale: |

|

Student Activity and Grouping: |

Prior to this activity, have students read about Coffin’s early experiences with slavery, as well as Chun’s background as a South Korean missionary. |

Developmental needs: |

|

ESL students may have difficulty with the Coffin document. Group presentations as a solution? |

||

|

Progress Monitoring: |

|

Achieve state content standards: |

|

|

||

|

Closure – Students Construct a New Organizer of the Content |

||

|

Instructional Strategy: |

Film Viewing of Seoul Train |

Rationale: |

|

Student Activity and Grouping: |

|

Developmental needs: |

|

|

||

|

Summative Assessment: |

Students will write a reflection piece after viewing the film, focusing on how they feel the situation today is similar and different from the American UR. |

Achieve state content standards: |

|

|

||

Background Information on Chun Ki Won

Known to some as “Robin Hood” and the “Asian Oskar Schindler” for helping lead over 500 North Korean refugees to safety in Mongolia, Thailand and Cambodia, Chun is a South Korean businessman turned pastor. His first exposure to the North Korean refugee issue came in 1999, while visiting Northeastern China for business. There he witnessed the sale of a North Korean woman to a Chinese man, her husband powerless to prevent the act. He also saw the body of a North Korean shot in the back trying to cross the Tumen River into China. These events led to Chun’s involvement as a prominent player in the secret escape network known as the Seoul Train.

Chun was arrested in 2001 at the Mongolian border for orchestrating an escape party for a group that included twelve men, women and children. After eight months in a Chinese prison, he was released to South Korea and banned from future entry into China. This escape attempt is documented in the film Seoul Train. Chun continues to build his underground network, and opened a liaison office in Washington D.C. shortly after his release.

Source: pbs.org (http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/seoultrain/update.html)

Background Information on the China/NK Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad featured in SEOUL TRAIN is made up of covert multinational cells of relief workers and volunteers who have led hundreds of refugees to freedom over vast stretches of unforgiving Chinese territory.

South Koreans make up the bulk of the volunteers, others are Japanese, Western or ethnic Koreans living in the U.S. or Europe. These networks provide refugees with a place to hide from authorities, as well as money, clothing, transportation and sometimes fake identification papers. Activists also prepare refugees for their journey by showing them videotaped footage of escape routes and teaching them how to get past suspicious citizens or border guards. The network uses drug traffickers and human smugglers who have connections with Chinese border guards, paying them up to $1,000 per person to sneak North Koreans across.

Every Underground Railroad worker, even those who help refugees across the smallest distances of two to three kilometers, operates in constant danger of discovery by North Korean agents and Chinese authorities. In desperate attempts to save themselves, refugees sometimes even inform upon the very workers who risk their lives to smuggle them out of China.

The chain of secret safe houses and hidden routes of the Underground Railroad evolved in the mid-1990s, when a deadly famine caused many North Koreans to leave their homes for neighboring China in search of food. In 1997, refugees poured into China when the effects of the famine hit their peak. Today, experts estimate that there are 250,000 North Korean refugees living underground in China.

The Safe House

Refugees who make contact with members of the Underground Railroad are brought to a safe house, where they are nursed back to health (many refugees arrive in China starved or injured), clothed and questioned about their reasons for leaving North Korea.

Railroad workers, as activists call themselves, then choose small groups of refugees to attempt a highly organized journey according to conditions and gut instinct. Before leaving, refugees are instructed how to pass as South Korean tourists in China. Most carry nothing with them.

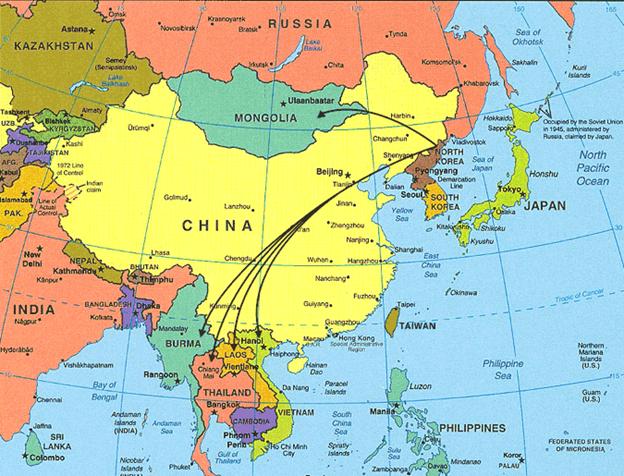

The Route

The most popular path along the Underground Railroad runs from China’s Jilin province across the Gobi Desert to Mongolia. It is a rough, four-day trip by train, car and foot. Once refugees reach the border, they must crawl under a seven-foot barbed wire fence to reach Mongolia. Activists bribe guards along the border to ensure that the defectors will be allowed to reach the South Korean embassy in the Mongolian capitol of Ulan Bator.

A “Southeast Asian route” has existed since 1997 but, until recent security crackdowns near the Mongolian border, was seldom used due to its long distance. It takes three to ten days to travel from the Chinese-North Korean border to Southeast China, and trains are one of the few modes of travel available. Activists may also hire drivers to ferry refugees from point to point.

Each moment of the journey out of China is a risk for the refugees and those who help them along the Underground Railroad. Anyone—including a refugee—could be a government agent sent to gather information for authorities who want to break down activist cells. Tension among refugees can also cause trouble. Safe houses have been raided because neighbors have overheard refugees arguing.

Source: pbs.org (http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/seoultrain/railroad.html)

Seoul Train Route Map

Source: pbs.org (http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/seoultrain/railroad.html)