Erin Peabody

Lesson Plan for the Underground Railroad

Class/Grade: 10th Grade Honors United States History I

The Underground Railroad: Fight and Flight

Overview: In this lesson, students will learn the dangers and attitudes of those who took flight along the Underground Railroad. The students will get an understanding of the dangers faced by the runaway slaves and the violence and courage inherent in the journey.

Suggested Time: 2 class periods of 45 minutes

NJ Standards

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

1. Demonstrate an understanding of the Underground Railroad.

2. Analyze primary documents of the 1st half of the 19th century.

3. Organize data on the dangers of the Underground Railroad.

4. Create a thesis that addresses the conclusions created.

5. Complete a DBQ Assessment.

Resources/Material

1. Teacher Handouts (found within this lesson)

2. Notebooks and Writing Utensils

3. Chalkboard or Dry Eraser Board with chalk or markers

Activities/Procedures:

1. Teacher will write the words Underground Railroad on the board. Students as a group will brainstorm people, ideas, and thoughts on the topic. Teacher or a student will write the responses by the student. (Anticipated answers vary from Harriet Tubman, path to the North, to safe houses and conductors.) Teacher will direct discussion on the topic.

2. Teacher will introduce the idea of the fight along the Underground Railroad. Teach will ask students to discuss with the students the dangers they feel were part of the Underground Railroad.

3. Students will break up into groups of 3-4 students. Students will be given handouts to examine. Students will discuss the items in the group and individually complete chart that has student observations from the documents.

4. For homework, students will answer the following DBQ question.

Assess the statement: Violence and danger were a strong aspect of a slave’s journey along the Underground Railroad. GRAHAM REVIEW

Evaluation and Assessment:

1. Class Discussion - 10 points

2. Complete Chart - 20 points

3. Essay – 100 points

Possible Extension Activity:

Have students create a two week journal of a runaway slave and the dangers he/she faced on their journey to freedom. Journals should reflect the information learned from the lesson.

Erin Peabody

Lesson Plan for the Underground Railroad

Class/Grade: 10th Grade United States History I and Kindergarten

The ABC’s of the Underground Railroad

Note: Great success in teaching can be found when students become the teacher. This lesson is created as a way to motivate students found in the less academic classes where a majority of students are learning disabled. A partnership is to be created between a US History teacher and kindergarten teachers in the school district. The lesson will work best as a field trip as the culminating activity.

Overview: In this lesson, students will learn the basics of the Underground Railroad. Students will become familiarized with the places, people, and the ideas

Suggested Time: 4 class periods of 45 minutes with an additional morning or afternoon with a field trip to a local elementary school trip.

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

1. Demonstrate an understanding of the Underground Railroad.

2. Analyze primary documents.

3. Collectively create an ABC Coloring Book of the Underground Railroad.

4. Teach the lesson they learned to kindergarten students.

Resources/Material

1. Computers with internet access

2. Sheets of plain, white paper and writing utensils.

3. Photocopier

Activities/Procedures:

1. Teacher will review with students what a primary document is.

2. Teacher will review that literacy ability and language of the average kindergarten student.

3. Teacher will review with the class the topic of slavery and life slaves lived including work and family.

4. Teacher will introduce the term Underground Railroad to the class. Teacher will use handout on the definition of the Underground Railroad created by Professor Mathew Pinsker to organize discussion.

5. Students will be put in pairs and assigned letters of the alphabet. Students will locate a primary document related to that letter of the alphabet for teacher approval. An example is a speech by Frederick Douglas for the letter D or the use of the term Conductor for the letter C. (Note: For very low functioning students, documents can be researched by the teachers and assigned to the students.)

6. Students are to create a page of the coloring book for each letter of the alphabet they were assigned. The page should have the letter in the upper right hand corner and the person/place/idea used for the letter. The page must have on the bottom information in the person/place/idea used. Taking up the most room on the page should be a picture either independently drawn or found on the internet for kindergarten students to color. The page must reflect knowledge learned from the researched primary document.

7. Teacher will collect the pages and organize the book. Extra credit can be assigned to a student to do the cover page. Teacher is to photocopy enough books to cover the number of kindergarten students that will receive the book.

8. During a field trip to the elementary school, the high school students are to be broken into groups of 3 to 4 students each. The High School students can either visit a multitude of kindergarten classes and work in small groups with the kindergarteners or have a one group of high school students visit one class.

9. In the kindergarten class, the high school students are to read the book to the kindergarten class. The high school students should share what they learned about the Underground Railroad. The kindergarteners can bring the books home to color and share what was learned with their families or left in school and reviewed at the discretion of the kindergarten teachers.

Evaluation and Assessment:

1. Class Work – 100 points

2. Creation of Pages - 100 points

3. Field Trip – 100 points

Document One

(Written and copyrighted to Professor Matthew Pinsker)

Underground Railroad: A New Definition

The Underground Railroad was a metaphor used by northern abolitionists and free blacks to describe and publicize their efforts at helping runaway slaves during the years before the Civil War. While secrecy was often essential for particular operations, the general movement to help fugitives was no secret at all. Underground Railroad operatives in the North were openly defiant of federal statues designed to help recapture runaways. Theses agents used person liberty laws, which aimed to protect free blacks residents from kidnapping, as a way to justify their fugitive aid work. Vigilance committees in northern cities such as Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and Detroit formed the organized core of their effort. These committees often worked together and provided legal, financial and sometimes physical protection to any black person threatened by kidnappers or slave-catchers. Notable vigilance leaders included William Still in Philadelphia, David Ruggles in New York, Lewis Hayden in Boston and George DeBaptiste in Detroit. There were also thousands of other individuals, usually motivated by religious belief, who helped fugitives in less systematic but still bravely defiant ways during the decades before the Civil War. Though all of these Underground Railroad figures operated with relative impunity in the North and Canada, southern operatives faced grave and repeated dangers and thus maintained a much lower profile. This is one reason why Harriet Tubman, an escaped slave herself, was such a courageous figure. Her repeated rescues inside the slave state of Maryland became the basis for her legendary reputation as “Moses.” Though Underground Railroad agents such as Tubman freed only a fraction of the nation’s slaves (probably no more than several hundred each year out of an enslaved population of millions), their actions infuriated southern political leaders, dramatically escalated the sectional crisis of the 1850s, and ultimately helped bring about the Civil War and the end of slavery in the United States.

Erin Peabody

Lesson Plan for the Underground Railroad

Class/Grade: 10th Grade United States History I

The Role of Central New Jersey in the Underground Railroad

Overview: In this lesson, students will be able to see how their hometowns and neighborhoods played a central role in the movement of runaway slaves to the North. The lesson will reinforce map skills of local areas.

Suggested Time: 3 class periods of 45 minutes

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

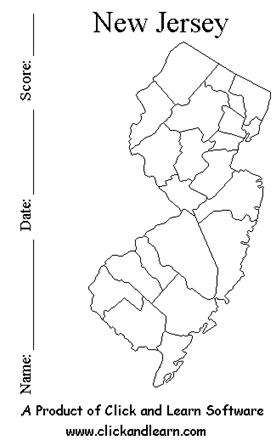

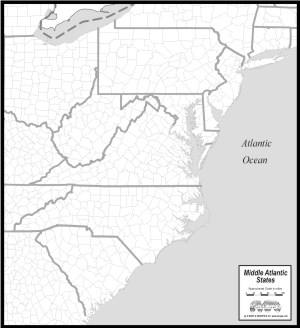

1. Create a map of the New York/Pennsylvania/New Jersey area of the mid 19th century.

2. Identify the free black population of New Jersey.

3. Identify New Jersey’s houses that have been identified as part of the Underground Railroad System.

4. Identify attitudes of present in New Jersey in regards to slavery.

5. Create a thesis on why Central New Jersey played a pivotal role in the Underground Railroad.

Resources/Material

1. Teacher Handouts (found within this lesson)

2. Crayons/Color pencils

Activities/Procedures:

1. Teacher will review the term Underground Railroad to the class. Teacher will use handout on the definition of the Underground Railroad created by Professor Mathew Pinsker to organize discussion.

2. As a class, teacher will read the proclamation passed by New Jersey Governor James McGreevey that addressed the role of New Jersey in the Underground Railroad.

3. Students will be given blank map of the New York/Pennsylvania/New Jersey area. Students are to place on the map the following:

a. New York

b. Pennsylvania

c. New Jersey

d. Philadelphia

e. New York City

f. Trenton

g. New Brunswick (Teacher will explain that the towns incorporated into the High School (Spotswood, Milltown, Helmetta) were not towns in the mid 19th century.

4. Students will be given an empty county map of New Jersey along with the census of free blacks living in New Jersey. Students will label the map according to the counties and create a visual representation of the number of free blacks on the map by using different colors to represent different amounts of people.

5. Students are to examine the four sites designated as Underground Railroad sites in New Jersey. Students are to read about each site and label them on the map.

6. Students are to read a speech given in New Jersey by Charles Beecher in 1851. Students are to identify attitudes and thoughts presented in the speech.

7. Students are to write a thesis that addresses the role of Central New Jersey in the Underground Railroad.

Evaluation and Assessment:

1. New York/Pennsylvania/New Jersey Area Map - 10 points

2. County Map of New Jersey - 40 points

3. Thesis – 50 points

Possible Extension Activity:

For more academic students, students can write a paper in defense of their thesis. For less academic students, students as a class can create a visual display of their research to be displayed at the local library or municipal center.

Document One

(Written and copyrighted to Professor Matthew Pinsker)

Underground Railroad: A New Definition

The Underground Railroad was a metaphor used by northern abolitionists and free blacks to describe and publicize their efforts at helping runaway slaves during the years before the Civil War. While secrecy was often essential for particular operations, the general movement to help fugitives was no secret at all. Underground Railroad operatives in the North were openly defiant of federal statues designed to help recapture runaways. Theses agents used person liberty laws, which aimed to protect free blacks residents from kidnapping, as a way to justify their fugitive aid work. Vigilance committees in northern cities such as Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and Detroit formed the organized core of their effort. These committees often worked together and provided legal, financial and sometimes physical protection to any black person threatened by kidnappers or slave-catchers. Notable vigilance leaders included William Still in Philadelphia, David Ruggles in New York, Lewis Hayden in Boston and George DeBaptiste in Detroit. There were also thousands of other individuals, usually motivated by religious belief, who helped fugitives in less systematic but still bravely defiant ways during the decades before the Civil War. Though all of these Underground Railroad figures operated with relative impunity in the North and Canada, southern operatives faced grave and repeated dangers and thus maintained a much lower profile. This is one reason why Harriet Tubman, an escaped slave herself, was such a courageous figure. Her repeated rescues inside the slave state of Maryland became the basis for her legendary reputation as “Moses.” Though Underground Railroad agents such as Tubman freed only a fraction of the nation’s slaves (probably no more than several hundred each year out of an enslaved population of millions), their actions infuriated southern political leaders, dramatically escalated the sectional crisis of the 1850s, and ultimately helped bring about the Civil War and the end of slavery in the United States.

Document Two

(Found on www.state.nj.us)

|

|

|||

|

|

James E. McGreevey |

Regena Thomas |

|

|

State

of New Jersey |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Document 3

(Found on www.amaps.com)

Document 4

(Found on www.clickandlearn.com)

Document 5

(Found at http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu)

Counties of New Jersey and the Free Colored Population in 1850

Atlantic 217

Bergen 1,624

Burlington 2,109

Camden 2,230

Cape May 247

Cumberland 1,130

Essex 2,328

Gloucester 620

Hudson 500

Mercer 2,036

Middlesex 1,369

Monmouth 2,323

Morris 1,008

Ocean 140

Passaic 615

Salem 2,075

Somerset 1,711

Sussex 340

Warren 380

Document 6

(Found on the web site of the organization Aboard the Underground Railroad: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary.)

|

This house, constructed in the late 18th century, was home to the Grimes family, a Quaker family active in the New Jersey antislavery movement. Dr. John Grimes (1802-1875), the most noted and vociferous antislavery advocate in the family, was born in this house and lived here until 1828 when he moved to nearby Passaic County to practice medicine. In 1832, he moved back to the homestead in Morris County and subsequently relocated to the neighboring community of Boonton. New Jersey's citizens were divided over the issue of slavery. Many people in New Jersey were sympathetic to the southern slave owners who had economic as well as social ties to the state. This faction was challenged by another group, largely comprised of Quakers like the Grimes family, who publicly opposed slavery. Once arrested for harboring a runaway slave, Dr. Grimes was repeatedly harassed by supporters of slavery while living at this house and later at his home in Boonton. Dr. Grimes' participation in the Underground Railroad is substantiated in his 1875 obituary in the newspaper Jerseyman, that stated, "In the earlier days, his father's house, Mr. Jonathan Grimes of Parsippany (Mt. Lakes today), was a prominent station on the celebrated Underground Railroad. In later days it was transferred to his own home in Boonton through which many a poor runaway has been helped on his way to Canada. They came to him from Baxter Sayre, Esq. of Madison (long since dead) he forwarding them in the night to Newfoundland, the next station." |

|

Peter Mott (c. 1807-1881), an African American farmer, constructed this house around 1844 and resided there until 1879. According to persuasive oral testimonies, Mott and his wife, Elizabeth Ann Thomas Mott, provided refuge to escaping slaves during the years leading up to the Civil War. 1870 census records show that Peter Mott was born in Delaware, and Elizabeth Ann Thomas in Virginia, but do not indicate if they were born into slavery. Their names do not appear in New Jersey records until their 1833 marriage which is possible evidence that one or both of the Motts may have escaped slavery and fled to New Jersey. The Motts settled in a free black community known as Snow Hill which later merged with a neighboring settlement called Free Haven. Snow Hill, founded in the early 19th century, may have take its name from Snow Hill, Maryland, reputed to be the place of origin for many of its founding residents. Free Haven was developed in 1840 by Ralph Smith, a white abolitionist who was the first Secretary of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, an antislavery organization founded in 1838. Smith named his development Free Haven to signify its role as a refuge from slavery and sold lots at low prices to free African Americans for homesites. In 1907, Snow Hill and Free Haven were renamed Lawnside which became the only ante-bellum, black community to become an incorporated municipality in the state of New Jersey. Peter Mott bought the first of three parcels of land on which his house was constructed from Jacob C. White, Sr., a wealthy African American dentist and active participant in the Underground Railroad. Mott became an influential local leader and served as a minister to Snow Hill Church, today named Mount Pisgah AME Church, and founded its Sunday School in 1847. Peter Mott's legacy as an Underground Railroad conductor survives because of his prominence in a free black settlement, his ties to other known Underground Railroad participants, and the strong oral history traditions of the remarkable community of Lawnside. |

![]()

|

|

|

|

nj3 |

The small, concrete masonry church known as Bethel AME Church is as a rare, surviving African American institution associated with multiple participants in the Underground Railroad. Located in the heart of the black community of Springtown in Greenwich Township, the church and its congregation offered lodging to fugitive slaves travelling north after leaving Maryland's Eastern Shore and Delaware. Oral histories attest that Harriet Tubman used the Springton/Greenwich station from 1849-1853 during her passage north through Delaware to Wilmington - one of her most famous routes.

The original congregation of Bethel AME Church had previously been members of various Methodist Episcopal churches in southern New Jersey. Until the early 1800s, white and black Methodist Episcopals worshipped together at these churches, as the members were all vehemently opposed to slavery. But as membership grew, Methodist slaveholders joined these churches and pressured church leaders to soften their anti-slavery position. Eventually, black members found themselves unwelcome, and in Greenwich they formed the African Society of Methodists, which by 1810 had purchased a small parcel of land and a cabin or house. By 1817, the congregation joined the newly chartered African Methodist Episcopal Church, which was formed in Philadelphia. When their first church was destroyed by fire in the 1830s, the present Bethel AME Church was built one mile away form the original site in Greenwich Townshipand between 1838 and 1841. The new building was located next door to the home of Algy Stanford, a church member and Underground Railroad operator.

Greenwich was originally settled by Quakers in 1685. After the Manumission Act of 1786, which enabled Quakers to free their slaves without financial hardship, the village of Springtown gradually developed as Quakers starting selling small tracts of land to free blacks. By the time of the Civil War, Springtown had developed into a large group of free land-holding blacks which made the area ideal for abolitionist activity. For many fugitive slaves, Springtown was a temporary destination before moving on, for others it became the end of their running. Their presence swelled the size of Springtown and strengthened it as a force for abolition

|

By the end of the Revolutionary War, many Quakers and anti-slavery sympathizers had set aside land for freed slaves. African-American hamlets were established in secluded areas on portions of Quaker land throughout western New Jersey. Small Gloucester, also known as Dutchtown, emerged in the early 19th century as one of these African-American settlements. One well-known Underground Railroad route was the Greenwich Line that began in the hamlet of Springtown, led 25 miles north to Small Gloucester, and continued north to Mount Holly, Burlington and Jersey City, New Jersey. The communities along this route were ideal stations on the Underground Railroad as they were situated about 20 miles apart, surrounded by Quaker land which was often swampy or dense woods, and inhabited by many free African-Americans. For more than 10 years, Harriet Tubman helped operate this line. The Mount Zion African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, a small one-story frame church built in 1834, was one of the important Underground Railroad stations in Small Gloucester from the time of its construction until the beginning of the Civil War. Members of the Mt. Zion AME church supported the Underground Railroad and actively provided protection, supplies and shelter for runaway slaves. The church was always a safe haven, and several original members of the congregation, including Pompey Lewis and Jubilee Sharper, directed conductors, engineers and slaves north after taking care of their personal needs. A secret, three foot by four foot trap door in the floor of the church's vestibule provided access to a hiding place in the crawlspace under the floor. The AME Church was organized nationally in 1816 under the leadership of Richard Allen, a very successful African-American circuit preacher. Allen and all AME circuit preachers played an important role in the protection and movement of runaway slaves as they moved through counties and conveyed directions, relayed messages and provided shelter. |

Document 7

(Found at http://antislavery.eserver.org)

The Duty of Disobedience to Wicked Laws.

_____________

A SERMON

ON THE

FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW.

BY

CHARLES BEECHER,

NEWARK, N.J.

___________

Newark, N.J.:

J McILVAINE, 121 MARKET STREET.

….In order, then, to test the law under consideration, I shall begin back at the constitutional clause on which it rests:--

“No person held to service or labor in one State before the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered upon claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due.” –Const. U.S., Art. 4, Sec. 2.

IS THIS RIGHT?

If this be right, then any law which means no more than this is right also. If this is wrong, then any law which means as much as this is wrong also. Is it right, then, for a free State to say that an escaping slave shall be delivered up?

This at once raised a question of natural right. Has a man, made in God’s image, a right to himself greater than another man has to him? Has a man in the interior of Africa a right to himself greater than the right of the slave-trader? Has the slave-trader any right to him after he has bought him? Our Government, by making the slave-trade piracy, say No. But if the slave-trader has no right, how can he sell his right? How can he transfer a claim when he no claim to transfer? But if so, has the Southern purchaser any right to the man? Can any number of fraudulent sales make a good title? And if the man had a right to run away from the slaver, has he not a right to run away from the slaver’s customer? But if the man has this right to himself, and to exercise that right, can a law of Georgia make that right wrong? And still more if he flies to a free State, can a law to deliver him up make it right? Why, then, could not a law make it right to catch him in Africa in the first instance? If it is right by law to recapture him in a free State, and reconsign him to slavery, it would be right by law to capture him Africa in the first place.

Therefore this clause of the Constitution is wrong. It legalized kidnapping. The legislature pronounces lawful here precisely what it condemns as piracy in Africa.

The deep instinct of every heart pronounces sentence here, as it will in the judgment day. Common sense decides. The slave is a man. He has a right to be free. It is wrong to deliver him up when he has made himself free. And that clause of the Constitution which says, Deliver him up, is wrong. It is unrighteous, and God will so declare it and treat it in the day of judgment.

This intuitive sense of right our fathers felt. In the act of inserting this compromise they knew and confessed that they were doing wrong. They were ashamed of themselves, and apologized for their conduct. They pleaded necessity. They confessed that they sold the truth for money.

![[graphic] Mount Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church

and Mount Zion Cemetery](LessonPlan--Peabody_files/image013.gif)

![[photo]](LessonPlan--Peabody_files/image014.jpg)

![[photo]](LessonPlan--Peabody_files/image015.jpg)