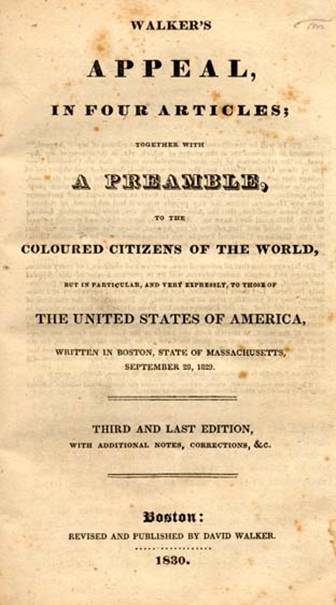

Document 1:

Source: Documenting the American South, accessed 7/25/07.

http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/walker/title.html

Discussion questions for Document 1:

1. When, where and by whom was this document published?

2. What assumptions would you make about the content of David Walker’s Appeal based on its cover?

3. What comments can you make about his use of the word “citizens” on the cover of his pamphlet?

4. Read his concluding paragraph: “Hear your language, proclaimed to the world, July 4th, 1776 – ‘We hold these truths to be self evident – that ALL MEN ARE CREATED EQUAL!! That they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness!!’ Compare your own language above, extracted from your Declaration of Independence, with your cruelties and murders inflicted by your cruel and unmerciful fathers and yourselves on our fathers and on us – men who have never given your fathers of you the least provocation!!!!!!”

Paraphrase David Walker’s argument in his conclusion. What is his message to African Americans, and how might different groups of white citizens, particularly in Boston, have reacted to this?

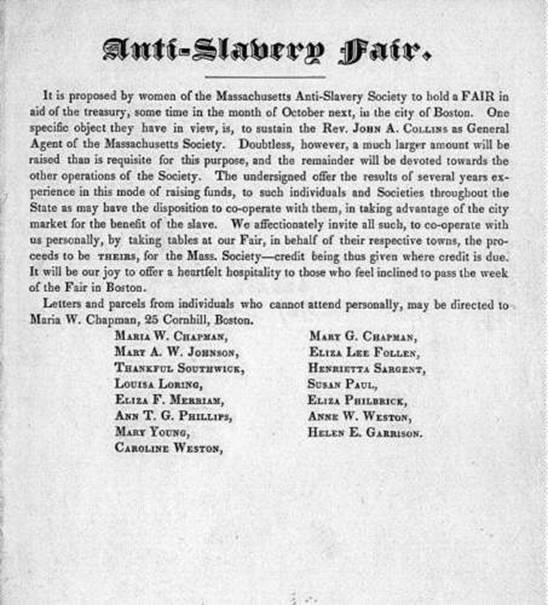

Document 2:

Source: The Library of Congress, accessed 7/25/07.

http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/african/afam005.html

Discussion questions for Document 2:

1. What is the purpose of this flyer? What is the purpose of the Fair?

2. What will happen to any money that is raised by the Fair?

3. What do all of the signers of the flyer have in common? What is particularly surprising about the information that is given about Maria W. Chapman?

4. What clues does this flyer offer about the extent of

antislavery efforts in Massachusetts at the time that the Fair was organized?

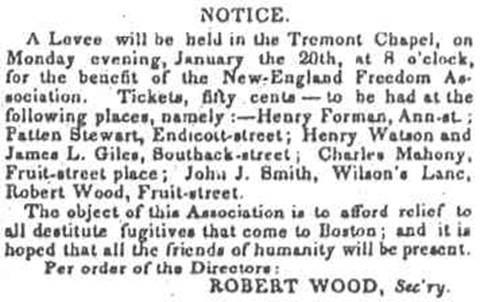

Document 3: An advertisement that appeared in The Liberator in January

of 1845.

Source: Primary Research, accessed 7/27/07.

http://www.primaryresearch.org/bh/liberator/524.jpg

Discussion questions for Document 3:

1. Define “levee” as used in the context of this advertisement. Who is holding this one, and when and where is it being held?

2. How much do tickets cost, and how can they be purchased?

3. What similarities are evident between Documents 2 and 3?

4. What does Robert Wood’s appeal to “all the friends of humanity” reveal about the nature of the abolitionist cause in Boston by 1845?

Document 4:

Source: The House Divided Project, accessed 7/29/07.

http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/ugrr/Liberator1850.cfm

Transcript

From the "Liberator," Nov. 1, 1850.

SLAVE-HUNTERS IN BOSTON.

Our city, for a week past, has been thrown into a state of intense excitement by the appearance of two prowling villains, named Hughes and Knight, from Macon, Georgia, for the purpose of seizing William and Ellen Craft, under the infernal Fugitive Slave Bill, and carrying them back to the hell of Slavery. Since the day of '76, there has not been such a popular demonstration on the side of human freedom in this region. The humane and patriotic contagion has infected all classes. Scarcely any other subject has been talked about in the streets, or in the social circle. On Thursday, of last week, warrants for the arrest of William and Ellen were issued by Judge Levi Woodbury, but no officer has yet been found ready or bold enough to serve them. In the meantime, the Vigilance Committee, appointed at the Faneuil Hall meeting, has not been idle. Their number has been increased to upwards of a hundred "good men and true," including some thirty or forty members of the bar; and they have been in constant session, devising every legal method to baffle the pursuing bloodhounds, and relieve the city of their hateful presence. On Saturday placards were posted up in all directions, announcing the arrival of these slave-hunters, and describing their persons. On the same day, Hughes and Knight were arrested on the charge of slander against William Craft. The Chronotype says, the damages being laid at $10,000; bail was demanded in the same sum, and was promptly furnished. By whom? is the question. An immense crowd was assembled in front of the Sheriff's office, while the bail matter was being arranged. The reporters were not admitted. It was only known that Watson Freeman, Esq., who once declared his readiness to hang any number of negroes remarkably cheap, came in, saying that the arrest was a shame, all a humbug, the trick of the damned abolitionists, and proclaimed his readiness to stand bail. John H. Pearson was also sent for, and came - the same John H. Pearson, merchant and Southern packet agent, who immortalized himself by sending back, on the 10th of September, 1846, in the bark Niagara, a poor fugitive slave, who came secreted in the brig Ottoman, from New Orleans - being himself judge, jury and executioner, to consign a fellow-being to a life of bondage - in obedience to the law of a slave State, and in violation of the law of his own. This same John H. Pearson, not contented with his previous infamy, was on hand. There is a story that the slave-hunters have been his table-guests also, and whether he bailed them or not, we don't know. What we know is, that soon after Pearson came out from the back room, where he and Knight and the Sheriff had been closeted, the Sheriff said that Knight was bailed - he would not say by whom. Knight being looked after, was not to be found. He had slipped out through a back door, and thus cheated the crowd of the pleasure of greeting him - possibly with that rough and ready affection which Barclay's brewers bestowed upon Haynau. The escape was very fortunate every way. Hughes and Knight have since been twice arrested and put under bonds of $10,000 (making $30,000 in all), charged with a conspiracy to kidnap and abduct William Craft, a peaceable citizen of Massachusetts, etc. Bail was entered by Hamilton Willis, of Willis & Co., 25 State street, and Patrick Riley, U. S. Deputy Marshal.

The following (says the Chronotype), is a verbatim et literatim copy of the letter sent by Knight to Craft, to entice him to the U. S. hotel, in order to kidnap him. It shows, that the school-master owes Knight more "service and labor" than it is possible for Craft to:

BOSTON, Oct. 22, 1850, 11 Oclk P. 115.

Wm. Craft - Sir - I have to leave so Eirley in the moring that I cold not call according to promis, so if you want me to carry a letter home with me, you must bring it to the United States Hotel to morrow and leave it in box 44, or come your self to morro eavening after tea and bring it. let me no if you come your self by sending a note to box 44 U. S. Hotel so that I may know whether to orate after tea or not by the Bearer. If your wife wants to see me you cold bring her with you if you come your self.

JOHN KNIGHT.

P. S. I shall leave for home eirley a Thursday moring. J. K.

At a meeting of colored people, held in Belknap Street Church, on Friday evening, the following resolutions were unanimously adopted:

Resolved, That God willed us free; man willed us slaves. We will as God wills; God's will be done.

Resolved, That our oft repeated determination to resist oppression is the same now as ever, and we pledge ourselves, at all hazards, to resist unto death any attempt upon our liberties.

Resolved, That as South Carolina seizes and imprisons colored seamen from the North, under the plea that it is to prevent insurrection and rebellion among her colored population, the authorities of this State, and city in particular, be requested to lay hold of, and put in prison, immediately, any and all fugitive slave-hunters who may be found among us, upon the same ground, and for similar reasons.

Spirited addresses, of a most emphatic type, were made by Messrs. Remond, of Salem, Roberts, Nell, and Allen, of Boston, and Davis, of Plymouth. Individuals and highly respectable committees of gentlemen have repeatedly waited upon these Georgia miscreants, to persuade them to make a speedy departure from the city. After promising to do so, and repeatedly falsifying their word, it is said that they left on Wednesday afternoon, in the express train for New York, and thus (says the Chronotype), they have "gone off with their ears full of fleas, to fire the solemn word for the dissolution of the Union!"

Telegraphic intelligence is received, that President Fillmore has announced his determination to sustain the Fugitive Slave Bill, at all hazards. Let him try! The fugitives, as well as the colored people generally, seem determined to carry out the spirit of the resolutions to their fullest extent.

Discussion questions for Document 4:

1. What event is described in this article from The Liberator?

2. What event is the article referring to when it references “the day of '76”? What point is the author trying to make about the event in 1850?

3. What kinds of terms are used to describe officials and others in Massachusetts that are operating under the authority of the Fugitive Slave Law?

4. What is the general attitude of the resolutions taken by black residents in Boston in their response to the new Fugitive Slave Law? What other groups of people and types of responses are represented in this article?

5. How does the author feel about warnings from the President

that the Fugitive Slave Law will be enforced? What does this portend for Boston in the 1850s?

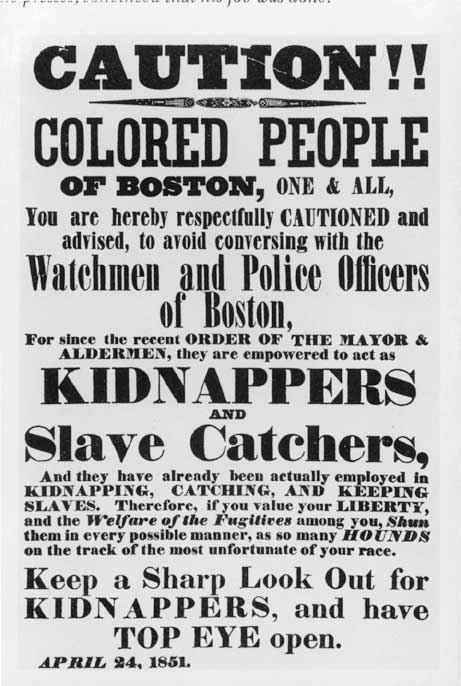

Document 5:

Source: Boston Public Library

Discussion questions for Document 5:

1. Who is the target audience of this poster, and what/who are they being warned about? Who might have been the publisher of this broadside?

2. If slavery was illegal in Massachusetts in 1851, why were watchmen and policemen threats to African Americans living in the city? What kind of incidents probably precipitated such a warning?

3. What does the language and phrasing of this warning suggest about the climate of the city in April of 1851?

4. How would you have reacted to this as an African American in Boston in 1851? As a white man or woman?

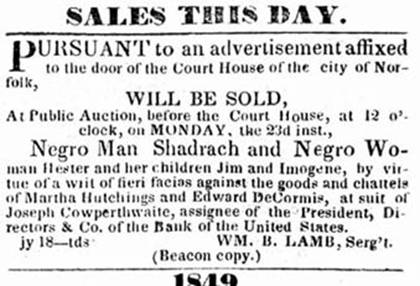

Document 6:

Advertisement of sheriff’s sale of Shadrach Minkins, 1849.

Source: Massachusetts Historical Society, accessed 7/25/07. http://www.masshist.org/longroad/01slavery/minkins.htm