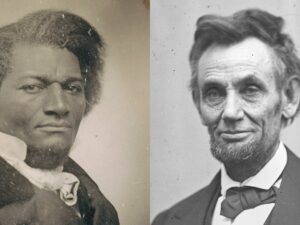

Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln: Ideology, Strategy, and Convergence

Jake Sokolofsky

As Frederick Douglass recollected, “While Lincoln hated slavery, and really desired its destruction, he always proceeded against it in a manner the least likely to shock or drive from him any who were truly in sympathy with the preservation of the Union, but who were not friendly to emancipation” [1]. In a nation rocked by the ravages of slavery and deeply divided over its future, Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln rose as the preeminent figures during the 1850s and 60s who, according to their similar ideological foundations, would guide the nation towards a realization of its founding principles of equality, justice, and freedom. Nonetheless, despite this conviction, Lincoln and Douglass passionately disagreed at various points in their careers about the most effective method to eradicate it, with Lincoln taking the moderate stance of the politician and Douglass the radical stance of the public figure. Over time, they would become more strategically comparable as Douglass’ focus shifted more towards politics and Lincoln’s towards emancipation, but this convergence was unique and virtually unforeseen in itself. Though often conflicting figures throughout the antebellum period and into the Civil War, Douglass and Lincoln as evidenced by the 1864 election were fundamentally similar in their antislavery ideology yet, via their context, occasionally differed in the nuances of strategy and timing.

The Moderate and Radical Path to 1864

Though both maintained a strong abhorrence towards slavery all of their lives, Lincoln and Douglass varied dramatically in their paths towards their goals of abolition and the positions they found themselves in to argue for such goals. Douglass was a radical, a man who came from slavery to be one of the most well-known abolitionists in America. Though originally a revolutionary, arguing that politics and the American system were fundamentally corrupted by slavery and thus should be completely disassembled, Douglass gradually moved towards Lincoln’s more moderate political position as time progressed [2]. Lincoln as a politician and leader of the Republican party was overall concerned with constructing a unified antislavery base, which entailed a degree of compromise and moderacy with more pro-slavery forces; Douglass, however, could not accept this [3]. For example, regarding the border states at the beginning of the war in 1861, Douglass argued that the Lincoln administration’s policies of appeasement were ensuring slavery’s continuation through a mistaken focus on reconciliation [4]. Lincoln, however, argued that the border states needed to be kept in the Union to have any hope of winning the war [5]. Even in his critique of the border state policies, though, Douglass’s transformation into more moderate politics continued to manifest. His solution to the problems of Lincoln’s policies was not revolutionary, but instead to make a policy of in-system abolition the focus of the war, therefore fundamentally similar to Lincoln’s strategies but differing in extent and intent.

Lincoln, however, was not nearly the compromiser Douglass thought he was. As the war continued to progress, Lincoln’s true positions on slavery were expressed more publicly as evidenced by the Gettysburg Address. Now more explicit about the cause and solution of the war, Lincoln used the Gettysburg Address in November 1863 to introduce his unswerving commitment to a “new birth of freedom,” implying a foundational change after the war and a true realization of America’s founding principles [8]. Douglass, however, ever pushing Lincoln, was quick to point out the necessary implications of his message: not only must slavery be deconstructed, but Blacks must have equal rights in all aspects of society for the principles to be realized [9]. Similar to his criticism of the Emancipation Proclamation, which he was wary of for being only a wartime measure (thus implying its impermanence), Douglass was again concerned about Lincoln’s potential for compromise in the face of political pressure following the war and throughout that new birth of freedom [10]. Douglass, even though aware of Lincoln’s convictions, nonetheless recognized the realities of his position: he knew that Lincoln may be forced to make certain concessions for strategic purposes, as much as he was against such compromises.

Douglass, however, had little to fear. Unbeknownst to Douglass, Lincoln, in the same month as their second meeting in August 1864, had written a memorandum that clearly outlined his staunch antislavery principles. Known as the “Blind Memorandum” because it was signed by his cabinet without being read, the short piece outlined his plans for the 1864 election: Lincoln would not give up on Emancipation nor postpone or alter the election no matter the political points he may gain from it or how much it may help his reelection effort [11]. Lincoln, by accepting his probable fate, unswervingly acted on his principles and commitments to emancipation and the American democratic system, two forces (and ideals) he saw as intricately intertwined. Lincoln, though constrained by the realities of what he could put into action with his position, nonetheless maintained his convictions to the best of his ability, especially nearing the 1864 election. In this way, Lincoln entered into Douglass’s territory with an unflinching principled commitment and refusal to negotiate or accept compromise, thus showing the extent of his ideological similarity with Douglass; if only Douglass had known the extent to which he and Lincoln shared the same ideals.

Though starting to coalesce in some regards, for both Douglass and Lincoln the 1864 election was a pivotal converging moment in strategy and ideology. Douglass, in an attempt to elect a more radical antislavery candidate than Lincoln, had strongly criticized Lincoln in favor of candidates like John Fremont and Salmon Chase [12]. When Lincoln received the Republican nomination, though, Douglass moved towards backing Lincoln because of the “two-pronged threat coming from the pro-slavery Democrats, on the one hand, and the comprising Republicans, on the other” [13]. As such, Douglass was leaning toward Lincoln until their meeting in August 1864, after which Douglass fully endorsed him as the best hope for the country. Douglass, therefore, became the strategic politician: he was “maneuvering within the Republican party” up until their meeting to accomplish what he wanted [14]. For Lincoln, the reelection and his second inaugural address was a time to truly speak his mind: his position no longer in jeopardy, and the position of the war much more in his favor, he could now emphasize his true motivations for the war effort and the future of the country in his second inaugural address. Their contexts converged simultaneously with their similar ideologies, allowing their strategies to converge as well. Though Douglass and Lincoln seemed completely converged both ideologically and strategically in this instant, with Douglass describing Lincoln’s address — a speech which would become a place from which Douglass would frequently draw in his later activism — as a “sacred effort,” their convergence was not entirely linear or traceable post hoc [15].

Convergence and the Second Inaugural Address

Stepping back, Douglass and Lincoln’s path to convergence in 1864-1865 was in no way linear, and Douglass’s “Mission of the War” speech, delivered in January 1864, just over a year before Lincoln’s inauguration, was the perfect representation of that. Douglass in this speech laid the outline for his thoughts on the Civil War, demanding that the war be fundamentally about abolition so that slavery would not return after the war’s end and that the United States could permanently distribute the principles of liberty and justice for all. Though he described it as “a war for the Union, a war for the Constitution,” Douglass made the case that without abolition the war would be for naught [6]. Here, though, Douglass’s transition towards more in-system reform efforts started to manifest: he did not desire the complete abolition of the American political system, only reform into what it could be. Though similar to Lincoln in this regard, Douglass had the luxury of expressing opinions like these to their fullest extent, a position that allowed the continuing construction of such radical ideas. Lincoln, on the other hand, did not have that privilege in early 1864, though he did have the power of policy making and tangible change if he were to act on his convictions. Douglass had some understanding of Lincoln’s antislavery convictions as a result of their 1863 meeting and the Gettysburg Address, but maintained reservations in early 1864 about Lincoln’s proclivity to compromise to maintain the political advantage [7]. Douglass’ antislavery and Lincoln’s antislavery differed in how they imagined their antislavery would manifest, and how it manifested in practice through their positions and actions. However much Douglass and Lincoln agreed in March 1865, their strategic convictions just a year prior would leave virtually no indication of their future strategic unification. Douglass’s “Mission of the War” speech and Lincoln’s Inaugural address held many conflicting viewpoints on fundamental issues, yet issues perhaps not fundamental enough to truly split Douglass and Lincoln.

Chiefly among these differences were their ideas on degrees of moral culpability. Lincoln, a man of unity and vision, outlined a path forward through hope in his Second Inaugural even amidst such a searing critique of slavery and the Confederacy, especially in how he outlined the war effort: “both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish” [16]. Douglass in his speech a year earlier, however, clashed with Lincoln’s assessment that the South had wanted to avoid war: “slavery—the peculiar institution—is aptly fitted to produce just such patriots, who first plunder and then seek to destroy their country” [17]. Much like most of their rise as political figures, Douglass chose the more fiery, radical language and indictment while Lincoln, at least superficially, clung to his hope of unity and reconciliation in the future. This difference in technique, though, was not necessarily indicative of a difference in personal conviction: the positions both men found themselves in (Douglass in changing opinion, Lincoln in responding to it) shaped their actions and as such their ideals on a level spanning pragmatic into futuristic.

The debate over action against slavery further split 1865 Lincoln and 1864 Douglass. Again in his address, Lincoln emphasized how slavery was bound to be removed by God, for an institution of such moral offense could only last so long under the Divine eye. Though likely drawing on Providence only to bring the religious listener closer to his political position — a piece of his broader unifying tactics — Lincoln’s determinism about the demise of slavery would likely seem to the January 1864 Douglass as a shirking of responsibility. As Douglass proclaimed, “our destiny is to be taken out of our own hands. It is cowardly to shuffle our responsibilities upon the shoulders of Providence.” Though perhaps in agreement on the foundational issue as slavery, the strategy around their message differed between a unifying and radicalizing tone and, implicitly, how the aftermath of the war was to be handled. Historian James Oakes describes, though, that Lincoln’s sentiment bore a strong enough resemblance to Douglass’s rhetoric on divine retribution that he could accept them, again showing Douglass’s moderate goals with the 1864 election and thus he and Lincoln’s strategic similarities [18].

Douglass’s difference in opinion between January 1864 and Lincoln’s inauguration in March 1865 reflected one thing: such unusual circumstances as the political turmoil before the election produced in Douglass a pragmatic approach that may have been burgeoning for much longer than outwardly expressed, thus moving him towards Lincoln’s strategy. Both men by the time of the inauguration seemed to agree on one obvious yet under-expressed principle: the degree to which reform/revolutionary efforts are successful varies in direct proportion to the degree to which the reform can be made through the system, implying a similar ideological and strategic standpoint for action. In the case of slavery, since it was in such fundamental contradiction to the founding doctrine of American politics, in-system reform efforts were more effective. Slavery was a unique issue because of its contradictions, and such abnormal circumstances produced in both men an adaptation of opinion that culminated in the similarity of their strategy in 1865.

The Importance of the Second Inaugural

Though outwardly an example of Lincoln and Douglass’s ideological and strategic convergence, the realities of their meetup immediately following Lincoln’s address underscores a more important point how their contexts and motivations affected them. Douglass, when asked by Lincoln (who made a point to highlight Douglass as one of his most trusted friends) in front of a large crowd what he had thought of his speech, replied that it was a “sacred effort,” a position he would maintain for the rest of his life. However, just like his August 1865 meetup with Lincoln, both men could have had motivations that could be reciprocated by the other [21]. Douglass was physically surrounded by people sympathetic to Lincoln, an environment which would have likely been hostile to any strong criticism of Lincoln’s speech; Lincoln, for his part, could have used Douglass as the prominent Black figure that he was to bolster his posture as a progressive and radical president, someone who would truly confront the issues of inequality and injustice in the future. This meetup was a microcosm of their convergence around the election: they both recognized interests that could be fulfilled by the other, and embraced around their similar ideological stances and efforts at strategically moderate yet forceful politics.

The possibility of both of these motivations for Lincoln and Douglass, however unlikely or untrue they may be, nonetheless provide an important perspective in quantifying their relationship and convergence as a whole: these were men in the public eye who were, in often unseen ways, controlled by the realities of their situations and in many ways acted accordingly as they saw fit. Moreover, their strategies converged as they used the situations around them to appeal to a broader audience than perhaps normal in order to garner more support for their respective causes. The possibility that they may have been altered by their pathways forward towards their broader goals makes the question of convergence and its necessity over the long term almost impossible to answer, though implies a similarity in their strategy and ideology in that moment especially as related to their context.

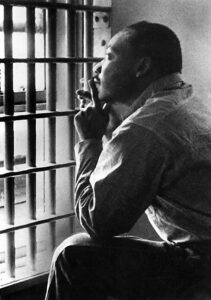

Martin Luther King on Lincoln and Douglass

The debate over pragmatism versus radicalism and reform versus revolution is present in every sociopolitical struggle and was especially relevant in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s. Martin Luther King’s 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” adds that to that discussion, this time juxtaposing the White moderate with himself and the rest of his movement who actively challenged discrimination through civil disobedience to force change. The White moderate, according to MLK, were White people who “agree with you [MLK] in the goals you seek,” but who cannot agree with direct action because it “precipitates violence,” who is more focused primarily on law and order, and who works solely through the established system to effect change [22]. According to many of these principles, Lincoln was the White moderate who stayed within the system and focused on law and order. In his letter, for example, MLK wrote that he wished for a return to the former Church, an institution that “was not merely a thermometer that recorded the ideas and principles of popular opinion; it was the thermostat that transformed the mores of society.” Metaphorically, Lincoln would be the 1963 Church, and thus the White moderate: he morphed his public expression of his true opinions based on the state of the country and the position of the public mind at various points, a pattern exemplified in the radicalism of the Second Inaugural.

However strong the implications, MLK nonetheless made an explicit reference to Lincoln in that letter which in no way criticizes him; in fact, he calls Lincoln an extremist to make the case that his own “extremism” (herein using the White moderate’s term) is similar to efforts of renowned figures like Lincoln. Though seemingly paradoxical, King’s reason for his position on Lincoln manifests implicitly in his analysis of his position in the Civil Rights movement. King wrote: “I have tried to stand between these two forces, saying that we need not follow the do-nothingism of the complacent or the hatred and despair of the black nationalist.” In this way, King is the unifying figure, the middle-ground between two extremes who by themselves would accomplish little. Lincoln was this same type of leader, and King recognized in his own case and in Lincoln’s the necessity of some degree of moderacy to effect larger change, principally because the change could indeed be made through the system he was operating in.

MLK, Douglass, and Lincoln agreed on one foundational point: staunch personal convictions are the bedrock of all efforts toward progress and freedom. Efforts at reform and justice, therefore, should take pieces from MLK, Douglass, and Lincoln: MLK’s radicalism and unifying presence, Douglass’s passion and fervor, and Lincoln’s prowess in politics and unification. Ideology is multifaceted, and thus using liberatory ideology and opposing oppressive ideology should itself be multifaceted. Lincoln and Douglass represent the importance of ideological commitment, yet also the importance of adapting and changing their techniques based on their circumstances in pursuit of freedom and justice.

Citations

[1] Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, (London: 1882), 310.

[2] James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (New York: W.W. Norton, 2007), 13.

[3] Oakes, 55.

[4] Frederick Douglass. “Cast off the Mill-stone,” Douglass’ Monthly (Rochester, New York), September, 1861.

[5] Amy Murrell Taylor, “The Border States,” National Parks Service, August 14, 2017, [WEB].

[6] Frederick Douglass, “Mission of the War,” (speech, New York, New York, January 13, 1864), BlackPast, [WEB].

[7] Oakes, 216.

[8] Abraham Lincoln, “Gettysburg Address” (speech, Gettysburg, PA, November 19, 1863), Abraham Lincoln Online, [WEB].

[9] Oakes, 223.

[10] “Frederick Douglass,” History, last modified May 25, 2022, [WEB].

[11] “Abraham Lincoln, Blind memorandum, Washington, DC, August 23, 1864,” House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College, [WEB].

[12] Oakes, 227.

[13] Ibid, 234.

[14] Ibid, 228.

[15] Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, 321.

[16] Abraham Lincoln, “Inaugural Address,” (speech, Washington, DC, March 4, 1865), National Park Service, [WEB].

[17] Douglass, “Mission of the War.”

[18] Oakes, 240.

[19] Ibid, 230-231.

[20] Martin Luther King, Jr., Letter from Birmingham Jail, 1963, [WEB].