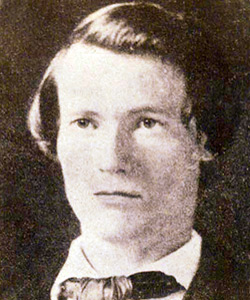

Albert Hazlett was among several of John Brown’s raiders who were not with their leader on the morning of October 18, 1859 when US Marines attacked the engine house at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Instead, Hazlett and Osborne Anderson watched the short battle from afar. The two men had left Harpers Ferry undetected late on October 17. After they could not find the five raiders who also escaped, they decided to head north – which eventually brought them into southern Pennsylvania. While Anderson lived to publish a book in 1861 about his experience, Hazlett was arrested in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania on October 22, 1859. Local authorities, however, at first thought that they had in custody “a man supposed to be Capt. Cook.” (John E. Cook was arrested three days later outside of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania). The initial confusion offered an opportunity for Hazlett, who claimed that he was actually William Harrison and had nothing to do with Brown’s raid. On October 29 Hazlett appeared before a judge in Carlisle on a writ of habeas corpus, but Hazlett’s claim that he was the wrong person failed to convince the judge. While “there is no evidence that we have any man in our custody named Albert Hazlett,” the court ruled that “we are satisfied that a monstrous crime has been committed [and] that the prisoner…participated in it.” Hazlett was sent back to Charlestown, Virginia on November 5 for a trial and was executed on March 16, 1860. Historian David Reynolds, who wrote John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, notes that the judge sent Hazlett back to Virginia “even though the evidence linking him to Harpers Ferry was circumstantial.”

Albert Hazlett was among several of John Brown’s raiders who were not with their leader on the morning of October 18, 1859 when US Marines attacked the engine house at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Instead, Hazlett and Osborne Anderson watched the short battle from afar. The two men had left Harpers Ferry undetected late on October 17. After they could not find the five raiders who also escaped, they decided to head north – which eventually brought them into southern Pennsylvania. While Anderson lived to publish a book in 1861 about his experience, Hazlett was arrested in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania on October 22, 1859. Local authorities, however, at first thought that they had in custody “a man supposed to be Capt. Cook.” (John E. Cook was arrested three days later outside of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania). The initial confusion offered an opportunity for Hazlett, who claimed that he was actually William Harrison and had nothing to do with Brown’s raid. On October 29 Hazlett appeared before a judge in Carlisle on a writ of habeas corpus, but Hazlett’s claim that he was the wrong person failed to convince the judge. While “there is no evidence that we have any man in our custody named Albert Hazlett,” the court ruled that “we are satisfied that a monstrous crime has been committed [and] that the prisoner…participated in it.” Hazlett was sent back to Charlestown, Virginia on November 5 for a trial and was executed on March 16, 1860. Historian David Reynolds, who wrote John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, notes that the judge sent Hazlett back to Virginia “even though the evidence linking him to Harpers Ferry was circumstantial.”

Tag: Newville

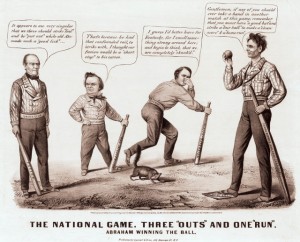

During the Election of 1860, the divided feelings did not stop the election of a new president. The election had several candidates, but the contest was actually between Douglas and Lincoln in the North and West and between Breckinridge and Bell in the South. Many thought the race would be very competitive, but Lincoln ended up dominating. In Cumberland County, Lincoln had an overwhelming victory. The more rural areas such as Hopewell and Fairfield that were mainly farmers, Lincoln won in a significant majority. In urban areas such as the Carlisle District and Newville, the race between the Republicans and Democrats was closer. The chart below gives the reported majority from the different districts in the county. The first column gives the total votes for Lincoln in the district. The second column shows the total of votes for Read, who is the elector for the districts. The third column gives the total votes for Bell, only prevalent in the more urban districts. Most of the rural districts only have votes for Lincoln, allowing him to have no competition in rural areas of Pennsylvania.

During the Election of 1860, the divided feelings did not stop the election of a new president. The election had several candidates, but the contest was actually between Douglas and Lincoln in the North and West and between Breckinridge and Bell in the South. Many thought the race would be very competitive, but Lincoln ended up dominating. In Cumberland County, Lincoln had an overwhelming victory. The more rural areas such as Hopewell and Fairfield that were mainly farmers, Lincoln won in a significant majority. In urban areas such as the Carlisle District and Newville, the race between the Republicans and Democrats was closer. The chart below gives the reported majority from the different districts in the county. The first column gives the total votes for Lincoln in the district. The second column shows the total of votes for Read, who is the elector for the districts. The third column gives the total votes for Bell, only prevalent in the more urban districts. Most of the rural districts only have votes for Lincoln, allowing him to have no competition in rural areas of Pennsylvania.

| Districts | Lincoln. | Read’s Ticket | Bell. | ||

| Carlisle Distict | 886 | 907 | 74 | ||

| Newville | 453 | 570 | 21 | ||

| Upper Allen | 33 | ||||

| Lower Allen | 103 | ||||

| East Pennsboro | 96 | ||||

| Plainfield | 83 | 1 | |||

| Penn Town | 14 | ||||

| Hampden | 19 | ||||

| Hopewell | 20 | ||||

| Mechanisburg | 130 | ||||

| North Cumberland | 32 | ||||

| Monroe | 117 | ||||

| Shippensburg District | 70 | ||||

| Leesburg | 27 | ||||

| Jacksonville | 22 | ||||

| Middlesex | 3 | ||||

| Silver Spring | 169 | ||||

| TOTAL: | 2083 | 1671 | 96 | ||

(Carlisle American, 7 November 1860.)

In the race for Governor, the majority of people in Pennsylvania voted for Andrew Gregg Curtin, a former Dickinsonian, in the election. This proved that the state had gone Republican by not less than 75, 000 Republicans state wide. Cumberland County followed the Pennsylvania results, as Lincoln/Hamlin received 40 percent of the popular vote.

Nationally, Lincoln received a total of 180 electoral votes, while the other candidates combined won 123. Breckinridge thought that he had some support in Pennsylvania, but Cumberland County did not support this assertion.

The Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana from the Library of Congress provides images from the election such as political cartoons, newspaper articles, candidate’s addresses and Republican and Democrat tickets. The Library of Congress has a great teacher resource on the Election of 1860. HarpWeek also provides cartoons from the election from Harper’s Weekly and other weekly journals. The