James Smith Colwell, who worked as a lawyer in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, was one of the men who answered President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers after Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Colwell joined the Carlisle Fencibles, a local volunteer company under the command of Robert Henderson, as a first lieutenant. Six weeks later the Fencibles left Carlisle for Camp Wayne in West Chester, Pennsylvania, where they received training and were designated Company A of the 7th Regiment, Pennsylvania Reserve Corps. His wife, Ann, had not been happy with that decision. “You left me without talking about it,” as Ann reminded him. While James admitted that “[he] err[ed] frequently,” he observed that “it [was] nearly always an error of the judgment & not of the heart.” Yet in this case he argued that it was impossible to get out of the army. “I do not see how I could get out of the service without bring[ing] disgrace and dishonour on myself & my little family,” as Colwell explained. Colwell had in mind his four children – two sons and two daughters. Colwell’s oldest daughter, Nannie, was about six years old in December 1861 when she announced in her “first letter” that she “[could] read” and “[sent him] a big kiss.” Colwell was able to return to Carlisle on furlough, but on September 17, 1862 he died during the Battle of Antietam. Local newspapers published obituaries, including the Carlisle (PA) American, which noted that “[Colwell’s] high moral character and exemplary life had made him a bright example in our midst.”When Civil War veterans in Carlisle established a local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic in February 1881, they decided to call it the Captain Colwell Post.

James Smith Colwell, who worked as a lawyer in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, was one of the men who answered President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers after Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Colwell joined the Carlisle Fencibles, a local volunteer company under the command of Robert Henderson, as a first lieutenant. Six weeks later the Fencibles left Carlisle for Camp Wayne in West Chester, Pennsylvania, where they received training and were designated Company A of the 7th Regiment, Pennsylvania Reserve Corps. His wife, Ann, had not been happy with that decision. “You left me without talking about it,” as Ann reminded him. While James admitted that “[he] err[ed] frequently,” he observed that “it [was] nearly always an error of the judgment & not of the heart.” Yet in this case he argued that it was impossible to get out of the army. “I do not see how I could get out of the service without bring[ing] disgrace and dishonour on myself & my little family,” as Colwell explained. Colwell had in mind his four children – two sons and two daughters. Colwell’s oldest daughter, Nannie, was about six years old in December 1861 when she announced in her “first letter” that she “[could] read” and “[sent him] a big kiss.” Colwell was able to return to Carlisle on furlough, but on September 17, 1862 he died during the Battle of Antietam. Local newspapers published obituaries, including the Carlisle (PA) American, which noted that “[Colwell’s] high moral character and exemplary life had made him a bright example in our midst.”When Civil War veterans in Carlisle established a local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic in February 1881, they decided to call it the Captain Colwell Post.

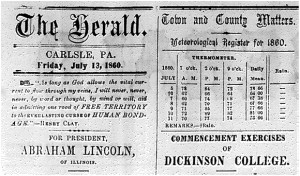

Dickinson College‘s 1860 commencement exercises occurred on Saturday evening, July 7, 1860. Two local papers’ contrasting reports on the evening demonstrate the partisan nature of nineteenth century newspapers. The Carlisle paper, The Herald, founded by Ekuries Beatty in 1799 originally supported the Whig party, but by 1860 printed articles with a strong Republican bias. In contrast the American Volunteer (another Carlisle paper) founded by William B. and James Underwood in 1814, reported the Democrat Party’s view of the news. The Volunteer charged Dickinson’s commencement speakers with attacking the “vulnerable” democratic president James Buchanan, himself a Dickinson alum from “when the institution was worthy of the name of a college.” According to the Volunteer many of the commencement speeches were full of dangerous “Abolitionist preaching” which must “be stopped.” Mr. George A. Coffey, of Philadelphia, spoke at an alumni gathering on the Wednesday before commencement and particularly offended the writers of the Volunteer who labeled his speech as “fierce and outrageous.” While the Herald admitted that Mr. Coffey introduced “topics which were offensive to many in the audience,” the paper concluded “it was a masterly speech.” Overall, the Herald presented a very different picture of the commencement exercises, carefully listing the names of the student speakers followed by a brief, usually complimentary, analysis of their speeches. The two Carlisle papers’ distinctly partisan accounts of Dickinson’s 1860 commencement reflect the political spin of the press throughout the Civil War era.

Dickinson College‘s 1860 commencement exercises occurred on Saturday evening, July 7, 1860. Two local papers’ contrasting reports on the evening demonstrate the partisan nature of nineteenth century newspapers. The Carlisle paper, The Herald, founded by Ekuries Beatty in 1799 originally supported the Whig party, but by 1860 printed articles with a strong Republican bias. In contrast the American Volunteer (another Carlisle paper) founded by William B. and James Underwood in 1814, reported the Democrat Party’s view of the news. The Volunteer charged Dickinson’s commencement speakers with attacking the “vulnerable” democratic president James Buchanan, himself a Dickinson alum from “when the institution was worthy of the name of a college.” According to the Volunteer many of the commencement speeches were full of dangerous “Abolitionist preaching” which must “be stopped.” Mr. George A. Coffey, of Philadelphia, spoke at an alumni gathering on the Wednesday before commencement and particularly offended the writers of the Volunteer who labeled his speech as “fierce and outrageous.” While the Herald admitted that Mr. Coffey introduced “topics which were offensive to many in the audience,” the paper concluded “it was a masterly speech.” Overall, the Herald presented a very different picture of the commencement exercises, carefully listing the names of the student speakers followed by a brief, usually complimentary, analysis of their speeches. The two Carlisle papers’ distinctly partisan accounts of Dickinson’s 1860 commencement reflect the political spin of the press throughout the Civil War era.

For modern scholarship on the subject of partisanship and the press see David T. Z. Minchin’s Just the Facts: How “Objectivity” Came to Define American Journalism (1998). The Library of Congress also provides an online newspaper directory to find more information on newspapers from across the country.

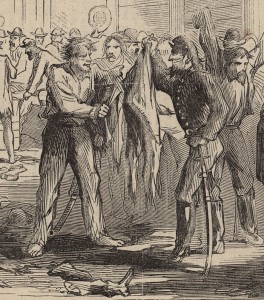

Before going to bed on October 10, 1862, Chambersburg resident William Heyser noted in his diary that he had “secreted some of my most valuable papers.” Confederate cavalry under the command of General J. E. B. Stuart had arrived several hours earlier and forced the town to surrender. Union forces had been caught by surprise and none were available to defend the town. “It would have been an act of madness to have made resistance…and would have involved the total destruction of the town,” as the Chambersburg (PA) Valley Spirit noted. The raid, as the Milwaukee (WI) Sentienel described, “was the most daring adventure of the war” so far. Besides gathering intelligence, one of the Confederate’s other objectives was to take as many supplies as possible. Horses were one key item and Alexander Kelly McClure, an assistant adjutant Union general, later recalled how ten horses were taken from his farm. (You can read McClure’s full account of the Confederate raid – “A Night With Stuart’s Raiders”- here). Yet as one Confederate soldier’s letter revealed, they also seized a number of other supplies. “I got 8 pair of boots, 4 over coats, 5 pair of pantaloons, 2 hats, 6 pair of socks, 6 pr. Draws, 6 over & under shirts, [and] some coffe & sugar” during the raid, as Edward Cottrell told his grandmother. As Confederates left Chambersburg on October 11, they burned warehouses that held government supplies. One contained ammunition and, as Heyser described, “the succeeding explosions of shells and power was tremendous.” While Union forces were dispatched to intercept and capture the raiders, General Stuart evaded them and returned to Virginia without any major engagements. You can read more about the raid in Emory M. Thomas’ Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart (1986) and Jeffry D. Wert’s Cavalryman of the Lost Cause: A Biography of J. E. B. Stuart (2008).

Before going to bed on October 10, 1862, Chambersburg resident William Heyser noted in his diary that he had “secreted some of my most valuable papers.” Confederate cavalry under the command of General J. E. B. Stuart had arrived several hours earlier and forced the town to surrender. Union forces had been caught by surprise and none were available to defend the town. “It would have been an act of madness to have made resistance…and would have involved the total destruction of the town,” as the Chambersburg (PA) Valley Spirit noted. The raid, as the Milwaukee (WI) Sentienel described, “was the most daring adventure of the war” so far. Besides gathering intelligence, one of the Confederate’s other objectives was to take as many supplies as possible. Horses were one key item and Alexander Kelly McClure, an assistant adjutant Union general, later recalled how ten horses were taken from his farm. (You can read McClure’s full account of the Confederate raid – “A Night With Stuart’s Raiders”- here). Yet as one Confederate soldier’s letter revealed, they also seized a number of other supplies. “I got 8 pair of boots, 4 over coats, 5 pair of pantaloons, 2 hats, 6 pair of socks, 6 pr. Draws, 6 over & under shirts, [and] some coffe & sugar” during the raid, as Edward Cottrell told his grandmother. As Confederates left Chambersburg on October 11, they burned warehouses that held government supplies. One contained ammunition and, as Heyser described, “the succeeding explosions of shells and power was tremendous.” While Union forces were dispatched to intercept and capture the raiders, General Stuart evaded them and returned to Virginia without any major engagements. You can read more about the raid in Emory M. Thomas’ Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart (1986) and Jeffry D. Wert’s Cavalryman of the Lost Cause: A Biography of J. E. B. Stuart (2008).

The Colwells are important to Carlisle’s Civil War history. James Colwell joined the Carlisle Fencibles, one of the military units formed in 1861, and was elected as First Lieutenant, despite being the oldest soldier at age 48. Shortly after leaving home, he wrote to his wife Annie to explain his motives for enlisting, saying, “I did it from a sense of right and duty…[M]y dear wife, the North is right and the South wrong…[P]osterity and the whole civilized world will so decide. Of this I have no doubt.”[i] Although Annie, a southerner from Baltimore, was not happy with his decision to join the army because it left her at home with four young children, she supported her husband and often sent him packages containing chicken, butter, jelly, and whiskey while he was away. Unfortunately, James was killed at Antietam in 1862. The couple’s nearly two hundred letters from the war were compiled by their great-grandson David Colwell into a book entitled The Bitter Fruits.

The Colwell family’s house can be seen today at 145 South Pitt Street in Carlisle, PA.

[i] David G. Colwell. The Bitter Fruits: The Civil War Comes to a Small Town in Pennsylvania (Carlisle, PA: Cumberland County Historical Society, 1998), 48.

Named for General Darius Couch, Fort Couch was one of three forts constructed in an attempt to control the high ground on the West Shore of the Susquehanna River to protect Harrisburg, the capitol of Pennsylvania. It was never finished because it was unneeded after the Confederates left the area. Fort Couch was built on the higher ground to the west of Fort Washington to protect it. Fort Washington, the primary fort in the area, was the only one to be brought to completion. It was located to the west of the Susquehanna River and is today on private property. The third fort’s location and name are unknown.

The forts primarily consisted of earthen platforms with mounted cannon. Because they anticipated that the Confederates would march into Harrisburg along the Carlisle Pike and across today’s Market Street Bridge, the cannons were primarily built facing the road. The forts were quickly constructed by railroad construction gangs. While some men were constructing the forts, others were busy cutting down trees and clearing the fields with fire in order to clear the line of fire to the road.

Civilians thought the forts were “formidable” and “impregnable” but military men thought they were built too quickly and would have rapidly fallen apart if attacked by cannon. These theories were not tested because the forts were never attacked.

There are many accounts that the soldiers stationed at Fort Couch did not treat the locals very well. One man noted that “the New Yorkers were here, and we fed them as long as we had anything. They turned out to be our worst enemies. They killed our hogs, chickens and so on.”[i] Another said that the New York troops were “a bad set of fellows …[who took] everything they could lay their hands on.”[ii] The men building the forts were not any better. They purposely went out of their way to antagonize Will Kiester, the only homeowner in the area, by building the fort through his vegetable garden and chopping down the trees in his front yard.

The original breastworks and the monument can be found at the intersection of 8th Street and Indiana Avenue in Lemoyne.

[i] Robert Grant Crist. Confederate Invasion of the West Shore – 1863. (Carlisle, PA: Cumberland County Historical Society, 2002), 25.

[ii] Ibid.

Locust Grove Cemetery has been known as the “colored cemetery.” Edward Shippen Burd, the grandson of the founder of Shippensburg, gave the land to the town’s African-American population in 1842. The land became a slave burial ground and was also home to Shippensburg’s first African-American church. Because the African-Americans owned the land, this site became a refuge for run-away slaves in the period of time before the Civil War. In 1861, the cemetery was officially segregated and continued to be so for the next 100 years.

Twenty-six free blacks from Shippensburg fought for the Union in the Civil War and are buried in the Locust Grove Cemetery. One group of Shippensburg brothers, the Shirks, fought for the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry because it was the first Union regiment to allow African-Americans to fight. John and James are buried in Locust Grove, while Casper is buried in Chalmette National Cemetery in New Orleans. John spent most of his time with the 55th Massachusetts in South Carolina. James was involved in the Fort Wagner Campaign and Sherman’s “March to the Sea” with the 54th Massachusetts. He was honorably discharged in 1865. Casper probably fought with the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry, but died on a boat and was buried in New Orleans surrounded by 12,000 Union soldiers who never made it home.

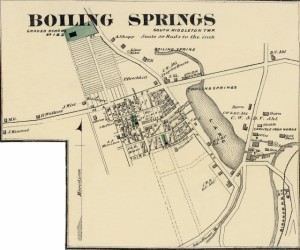

Boiling Springs, Pennsylvania embraced the transportation and protection of fugitive slaves moving northward across the Mason-Dixon Line. Daniel Kaufman (alternately spelled Kauffman), born in Cumberland County in 1818, laid out designs for the town and helped make his presence known. His support for the Underground Railroad strengthened in Boiling Springs, as indicated by the events of October 24, 1847.

Boiling Springs, Pennsylvania embraced the transportation and protection of fugitive slaves moving northward across the Mason-Dixon Line. Daniel Kaufman (alternately spelled Kauffman), born in Cumberland County in 1818, laid out designs for the town and helped make his presence known. His support for the Underground Railroad strengthened in Boiling Springs, as indicated by the events of October 24, 1847.

As shown by evidence later presented in court, thirteen slaves belonging to the Oliver family escaped in Maryland, crossed the border into Pennsylvania, and eventually found themselves in Kaufman’s barn in Boiling Springs. Kaufman consented to provide them with shelter and food, and within the next day he offered up his wagon to transport the slaves across the Susquehanna River. News of the fugitive slaves spread, and within a few short months the slave owner’s family filed a lawsuit against Kaufman.

The Court of Common Pleas of Cumberland County opened the case Oliver et al. v. Kaufman against Kaufman and two other known associates, Stephen Weakley and Philip Breckbill. The defendants argued that the suit could not be tried in state court as the issue pertained to federal law. Nevertheless, the jury delivered a verdict in favor of the plaintiff; Kaufman had to pay $2000 in damages. When a panel of judges of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court oversaw the case, their “majority opinion” notably argued “that Congress possesses the exclusive right to legislate on the subject [of fugitive slaves] and that State Legislatures have no right whatever” and could therefore not recover any damages. The Cumberland County Court’s ruling was reversed. The case continued in 1852, this time in a federal court, only to conclude in favor of the plaintiff and with Kaufman liable to approximately $4000 in damages and fines.

Kaufman’s case occurred during a period of heavy debate in Pennsylvania regarding state sovereignty and the adherence to federal mandates including the Fugitive Slave Laws of 1793 and 1850. Prior to the case seen in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania judges gave credence to the state’s “common law” and “clear right to declare that a slave brought within her territory becomes ipso facto a freeman,” as quoted by a law journal in Paul Finkleman’s An Imperfect Union: Slavery, Federalism, and Comity. traced the evolution of state sovereignty in Pennsylvania.

For a more detailed summary of the cases, the House Divided record of the case provides access to several primary documents, including newspaper articles and the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s decision to reverse the ruling of the case. Finkleman’s book puts Kaufman’s trial into context, but his summary of the case will help those even vaguely familiar with its nuances. LexisNexis, though requiring a subscription, grants access not only to the court documents, but to modern scholarship on the case’s wider importance in the debate on Federalism and state’s rights. In Robert Kaczorowski’s article “Federalism in the 21ST Century,” the Fugitive Slave Laws emerge as the focal point for a much wider debate on the intent of the Founding Fathers with regard to state rights and federal mandates.

A historical marker is located at Front & 3rd Streets in Boiling Springs.

Charles Albright and George Baylor both spent their formative years as students at Dickinson College, and their shared participation in the Union Philosophical Society helped define their experience on campus. Despite their immediate similarities on campus, Baylor enrolled in Dickinson six years after Albright left campus in pursuit of a profession in law. Baylor’s wealthy roots in Jefferson County, Virginia, his birthplace, only accentuated his stark differences with Albright, who grew up in Berks County, Pennsylvania. Albright also demonstrated his fervent opposition to slavery in the decade prior to the outbreak of war, a sentiment not shared by Baylor, who immediately joined the Confederate army in May 1861. Both Baylor and Albright enlisted in the military and went on to become respected leaders in their respective units. Their dedicated service brought the otherwise unlikely pair of Dickinson students together in April 1865 in northern Virginia.

Charles Albright and George Baylor both spent their formative years as students at Dickinson College, and their shared participation in the Union Philosophical Society helped define their experience on campus. Despite their immediate similarities on campus, Baylor enrolled in Dickinson six years after Albright left campus in pursuit of a profession in law. Baylor’s wealthy roots in Jefferson County, Virginia, his birthplace, only accentuated his stark differences with Albright, who grew up in Berks County, Pennsylvania. Albright also demonstrated his fervent opposition to slavery in the decade prior to the outbreak of war, a sentiment not shared by Baylor, who immediately joined the Confederate army in May 1861. Both Baylor and Albright enlisted in the military and went on to become respected leaders in their respective units. Their dedicated service brought the otherwise unlikely pair of Dickinson students together in April 1865 in northern Virginia.

After graduating with the Class of 1860, Baylor returned to the academy he attended in Virginia as a child to teach. He kept this position until May 1861 when he enlisted in the Confederate army as a private. By 1863, Baylor established his reputation as an indefatigable and effective cavalry leader. His successful raids through Virginia in 1863 and 1864 only strengthened this reputation from the perspective of Colonel J. S. Mosby, who ensured the appointment of Baylor as captain of the company formed in April 1865. Less than a week after its formation, the unit encountered Union troops near Fairfax Station, Virginia and Baylor reluctantly retreated. He did not know, however, that the colonel leading the Union force was Charles Albright, fellow Dickinson alumnus and member of the Union Philosophical Society.

Well before confronting Baylor’s soldiers in 1865, Albright first established his military record in the Union army as a volunteer in a company dedicated to the protection Washington, D.C. He spent much of his service in Pennsylvania, first as a leader in the Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry and then as the commanding officer of Camp Muhlenberg in Reading. In September 1864, after having moved throughout the state with the Volunteer Infantry, Albright led the Infantry’s 202nd Regiment against several raids conducted by Confederate soldiers in attempts to sabotage Virginia’s railways. Albright attempted to stop one such raid, planned by Baylor, on April 10, 1865.

Albright’s report of the raid and his unit’s victory over Baylor’s soldiers noted that those Confederate soldiers who were not killed or did not escape were taken prisoner. In a less formal account of the attack, Albright told his superior that he “whipped him like thunder.” As one would expect, Baylor’s memoirs detail the events in a much different manner. Of the battle Baylor said that “if the critic will carefully review the reports from the Colonel himself, the advantage will appear exceedingly small” and, responding directly to Albright’s description of the confrontation, “I hope the devil will never whip him any worse.” This chance meeting between Dickinson alumni, however separated by class, background, politics, or ideology, illustrated one way the war divided a single campus. Student populations at Dickinson divided fairly evenly between Union and Confederate allegiances. While the campus saw the early manifestations of these divisions among students, some class members saw it demonstrated on the battlefield.

Charles Rawn, a lawyer who lived in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, wrote over 11,000 daily entries between 1830 and 1865. The entire journal is now online thanks to the efforts of Pennsylvania University State Professor Michael Barton and the Historical Society of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. Rawn, who was born in Georgetown in July 1802, moved to Harrisburg in 1826 and got married seven years later. His journal entries largely contain notes about his daily life – from various legal matters to financial expenditures. While “he rarely mentioned grand ideas or personal feelings in his daily record,” Professor Barton argues that “[these] records are valuable guides to understanding everyday life in antebellum America.” Rawn was a “record keeper rather than a story teller,” as Baron explains. Yet Rawn’s journals include some interesting notes about political events in Harrisburg, including President-Elect Abraham Lincoln’s visit in 1861. On February 22 Rawn described:

“[Lincoln] rode in a Barouche drawn by 6 White Horses to Coverlys Hotel where he was addressed by Gov. Curtain & [replied?]. The enthusiasm of the people was perfectly and literally wild & unrestrainable…. Altogether it was such a day & time as Harrisburg has never before witnessed. The number Military here in time of the Buckshot Wars was approached nearly perhaps to the number here yesterday. Mr. L’s appearance is younger considerably than was generally expected and he is not so tall [nor so?] Rawboned as we had been given to believe from his pictures and what we had read.”

In addition, Rawn took detailed notes when he traveled into Virginia three months after Confederates attacked Fort Sumter in April 1861. On July 22, 1861, the day after the First Battle of Bull Run, Rawn observed:

“Dead, wounded and dying being brought in continually. I saw several of the wounded. One man with a Buck shot in the neck….From all accounts which of course are measurably wild and unforgettable [?] in a degree the slaughter on both sides has been immense—in the thousands. There was desperate fighting—desperate fright in some quarters and desperate getting out of the way in all many directions and in all imaginable disorder by some of our troops as I make out by the statements.”

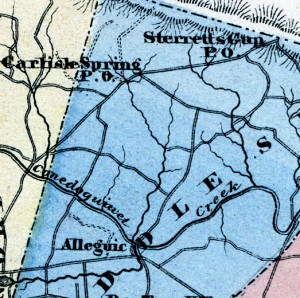

According to the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission, the farthest north point of the Union attained by an organized body of the Confederate Army was present day Pennsylvania Route 34, about 1 mile north of Carlisle Springs. The Pennsylvania Historical marker, erected in 1929, states that on the morning of June 28, 1863, an organized band of the Confederate Army of Robert E. Lee reached the farm of Joseph Miller near Sterrett’s Gap. There is no evidence as to whose command these Confederates belonged to. Check out ExplorePAhistory.com for more information and details on the historical marker.

According to the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission, the farthest north point of the Union attained by an organized body of the Confederate Army was present day Pennsylvania Route 34, about 1 mile north of Carlisle Springs. The Pennsylvania Historical marker, erected in 1929, states that on the morning of June 28, 1863, an organized band of the Confederate Army of Robert E. Lee reached the farm of Joseph Miller near Sterrett’s Gap. There is no evidence as to whose command these Confederates belonged to. Check out ExplorePAhistory.com for more information and details on the historical marker.

Another common conception of the farthest north point or high-water mark of the Confederate Army is a small grove of trees within a confined area known as “The Angle.” It was behind this location where the Union troops were positioned on July 3, 1863 during “Pickett’s Charge” which took place during the Battle of Gettysburg. The first government historian of the Gettysburg battlefield, John B. Bachelder, conferred the title “High Water Mark of the Rebellion” to the small grove or “copse” of trees. Bachelder’s influence led to the creation of the “High Water Mark of the Rebellion Monument,” dedicated in 1892. For more information the National Parks Service website and the Historical Marker Database provides further details, maps and images.

One other historical theory of the Confederate high-water mark is from Jeff Shaara’s Civil War Battlefields: Discovering America’s Hallowed Ground. Shaara contends that a monument representing the 11th Mississippi is the actual high-water mark. In his book he notes:

“I respect those who care deeply about paying homage to such noteworthy historical landmarks as the high-water mark. I speculate, however, that the copse of trees does not indicate the farthest advance of the Confederate troops that day. Drive just north, to the Bryan House. Walk to the stone wall on the left, peer over, and you will see the newest monument on the battlefield. This marks the spot where the battle flag of the 11th Mississippi was found as it lay across the stone wall. The 11th was part of the brigade commanded by Joe Davis, nephew of the Confederate president. By all information, a total of fourteen Mississippians reached this spot, farther into the Union position than the North Carolinians, at what is today labeled the high-water mark.”