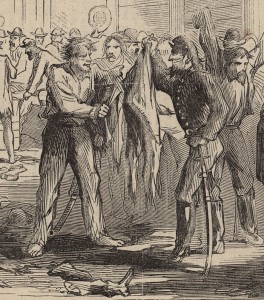

The skirmish at Oyster Point was a small engagement that took place in late June 1863 in Camp Hill, Pennsylvania between Confederate forces under General Albert G. Jenkins’ command and Union militia from New York under General William F. Smith’s command. After Confederates entered Mechanicsburg, General Jenkins set up artillery and sent Virginia cavalry in pursuit of Union militia who had been in the town. At Oyster Point the Confederates encountered two militia regiments from New York and Landis’ Philadelphia Battery of Light Artillery. Later that day General Jenkins ordered his force to withdraw to the Rupp House in Mechanicsburg. Confederates returned on June 29, but they were unable to dislodge the Union militia. The Battle of Sporting Hill took place on the following day as Confederates left Mechanicsburg and marched towards Gettysburg. As a veteran who served with the 22nd New York Regiment recalled:

While this skirmish was of no particular account in itself, it is really historic. It was at the furthest northern point which was reached by the invaders, and marks the crest of the wave of the invasion of Pennsylvania. The retreat of the Confederate force there commenced did not end until the Potomac was crossed. The success obtained must be largely ascribed to the gallant conduct of Landis’ Battery,….”

A historical marker is located at the intersection of 31st Street and Market Streets in Camp Hill. You can read more about this battle in an essay on ExplorePAhistory.com, Robert Grant Crist’s article “Highwater 1863: The Confederate Approach to Harrisburg” (Pennsylvania History 1963), and in Wilbur Sturtevant Nye’s Here Come The Rebels! (1965).