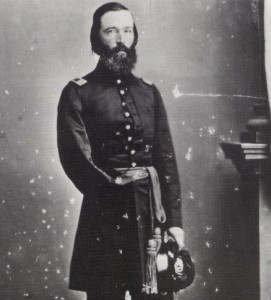

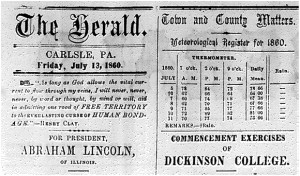

On September 23, 1897 Horatio Collins King, a member of Dickinson College Class of 1858, received a Medal of Honor for his acts of bravery during the battle of Five Forks. As quartermaster of the first cavalry division of the Army of the Shenandoah, King fought in one of the final Eastern battles of the Civil War in Five Forks, Virginia on April 1, 1865. Maj. General Philip Sheridan led 50,000 Union troops in a victory over a Confederate force only one-fifth the size. In his military history, Campaigns of the Army of the Potomac (2008), William Swinton explains the Union victory and capture of the Southside Railroad at Five Forks in terms the battle’s greater significance in the war. Within the eight days following the battle of Five Forks the Confederate Army had retreated from Petersburg and Richmond and General Robert E. Lee had surrendered his army to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse.

On September 23, 1897 Horatio Collins King, a member of Dickinson College Class of 1858, received a Medal of Honor for his acts of bravery during the battle of Five Forks. As quartermaster of the first cavalry division of the Army of the Shenandoah, King fought in one of the final Eastern battles of the Civil War in Five Forks, Virginia on April 1, 1865. Maj. General Philip Sheridan led 50,000 Union troops in a victory over a Confederate force only one-fifth the size. In his military history, Campaigns of the Army of the Potomac (2008), William Swinton explains the Union victory and capture of the Southside Railroad at Five Forks in terms the battle’s greater significance in the war. Within the eight days following the battle of Five Forks the Confederate Army had retreated from Petersburg and Richmond and General Robert E. Lee had surrendered his army to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse.

Nonetheless, for the soldiers who fought at Five Forks, the battle remained a personal experience. In his Civil War Journal (digitized in the Dickinson College database “Their Own Words”), Horatio King did not go to lengths to discuss the meaning of the battle and the Confederate retreat. Instead, King wrote a poignant passage describing a dead Southern soldier he encountered while collecting the wounded: “his face was raised toward heaven and the open eyes & sweet expression of countenance together with the hands uplifted as in prayer gave me the impression that he still lived.” Battles were personal affairs for generals as well, as exemplified by Gouverneur Kemble Warren’s obsession with Five Forks. After the battle, Sheridan relieved Warren of his command of the V Corps, and when Warren “personally sought of General Sheridan a reason for his order,” “he would not or could not give one.” After more than a decade of seeking an explanation, Warren finally received official recognition of his unjust treatment when President Rutherford B. Hayes authorized a court of inquiry on December 9, 1879.

The National Park Service has preserved Five Forks as part of the larger Petersburg National Battlefield. Their website contains Five Forks resources including multiple battle maps. J. Tracy Power’s Lee’s miserables : life in the Army of Northern Virginia from the Wilderness to Appomattox (1998) is a unique military history of the last year of the war that uses Confederate soldier’s letters and diaries as a primary source of evidence, giving readers a different angle on the battle of Five Forks.

Click on this 1865 Waud sketch of the battle to see other Five Forks images: