Sources

The key primary sources on on Dickinson Gorsuch and the Christiana Riot are William Still’s The Underground Rail Road (1872), David R. Forbes’ A True Story of the Christiana Riot (1898), and Jonathan Katz’s Resistance at Christiana: The Fugitive Slave Rebellion, Christiana Pennsylvania, September 11, 1851: A Documentary Account (1974). Important secondary sources include William Uhler Hensel’s The Christiana Riot and the Treason Trials of 1851: An Historical Sketch (1911), Thomas Slaughter’s Bloody Dawn: The Christiana Riot and Racial Violence in the Antebellum North (1991), and Fergus M. Bordewich’s Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement (2006). You can also read Mark G. Jaede’s short essay about the riot in the Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion (2007).

Places to Visit

The historic marker for the Christiana Riot was dedicated in May 1998 and is located south of Christiana on the Lower Valley road. In addition, the riot is mentioned on “The Underground Railroad and Precursors to War” historic marker at the intersection of Pennsylvania Route 462 and West Market Street in York, Pennsylvania. While William Parker’s house no longer exists, you can view a 3-D model on House Divided.

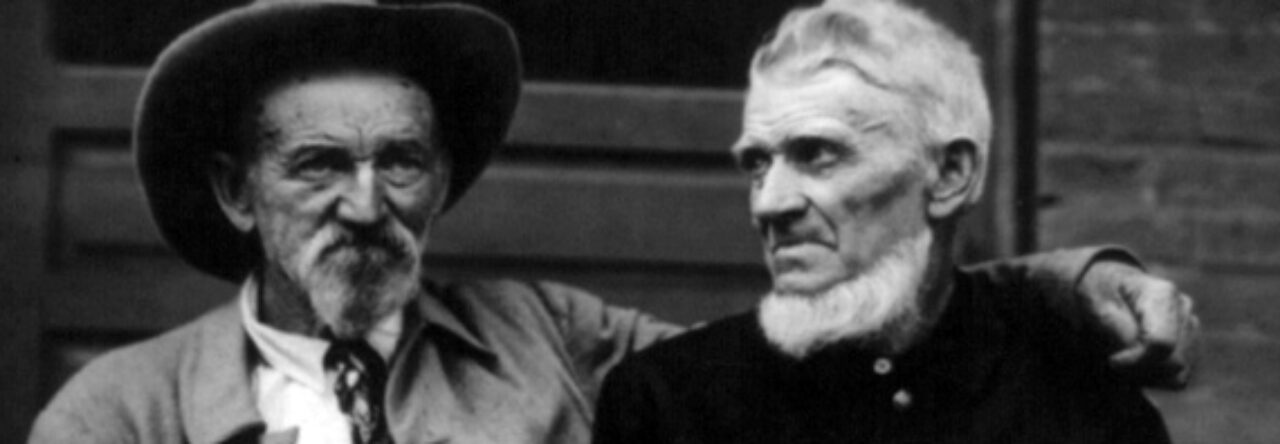

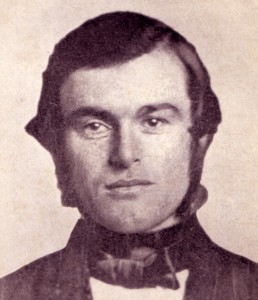

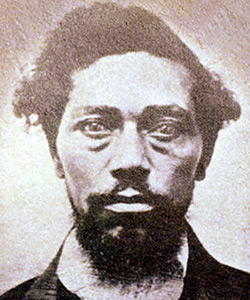

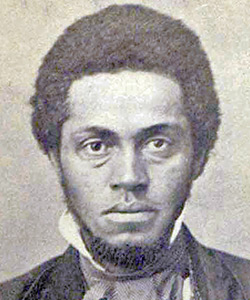

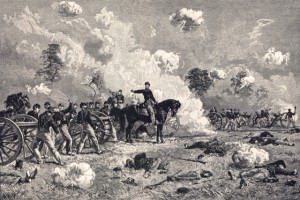

Images

Images related to the Christiana Riot are in the slideshow below: