Narrative

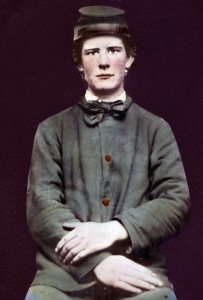

John Taylor Cuddy was born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania on October 17, 1844. His schooling was limited since he worked in the family business. In the late spring of 1861, like tens of thousands of his fellow Pennsylvanians, he was caught up in the excitement of the Civil War and President Lincoln’s call for volunteers. Carlisle and its surrounding area quickly brought together four companies of volunteers during April 1861. One of these, the Carlisle Fencibles under Captain Robert Henderson, took into its ranks the young Cuddy, who added a year to his age to avoid possible complications with his enlistment. This unit subsequently became Company A, 36th Regiment, 7th Pennsylvania Reserve Corps, and John Taylor Cuddy was mustered into this regiment as a private on June 5, 1861.

The 36th, after training at Camp Wayne near Philadelphia, joined the defense of Washington and spent some relatively quiet months before being engaged in the battles around Gaines Mill and Mechanicsville in June 1862. Cuddy’s response in letters home was one of relief and confidence that if he could survive three heavy encounters, he could come home unscathed. Action at the late summer 1862 Battle of Antietam followed for the 36th, although Cuddy may have been on leave when it was fought. As events balanced out the unit’s earlier inaction, the regiment fought bravely and well in the losing cause at Fredericksburg in December 1862.

Cuddy’s letters in the new year of 1863 reflect the exhaustion of men already counting down the days of their three-year enlistment. Cuddy’s own words are reflective of much of the popular response in the North to President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation (January 1, 1863). In scathing tone, the teenager predicted a long war now that “the rebels is fighting for ther rites.” In the same letter he hopes strongly that the division will go home to recruit replacements, hinting that many of the early enlistees, including Cuddy himself, were weary of war and would not return from any home assignment. A long period of relative inactivity protecting the national capital did not improve morale. Cuddy and his parents tried to arrange a home leave, enlisting the help of Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin. Though granted, permission for the furlough was forgotten in the turmoil of the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania in June 1863. Cuddy and the 36th remained in Washington, reduced to anxious letters home to find news of the course of Lee’s advance. In April 1864, Cuddy and his companions were tantalizingly close to their final days as soldiers when the 36th was ordered to join Grant’s attack towards Richmond. During the confusion of the first and second day of the Battle of the Wilderness, the 36th suffered disaster when it was cut off and forced to surrender all its 272 officers and men. There were no more letters home from the teenaged veteran, who when captured had just one month before the end of its enlistment. Cuddy was among those who were entrained and then marched to the notorious Andersonville Prison in Georgia. Sixty-seven men of the 36th perished in the horrendous conditions of the open camp. John Cuddy survived Andersonville, but when he and others in his company were transferred to another equally harsh camp in Florence, South Carolina, his shattered health gave way to the ravages of five months in captivity. There he died of illness and malnutrition on September 29, 1864, eighteen days before his twentieth birthday.

Family

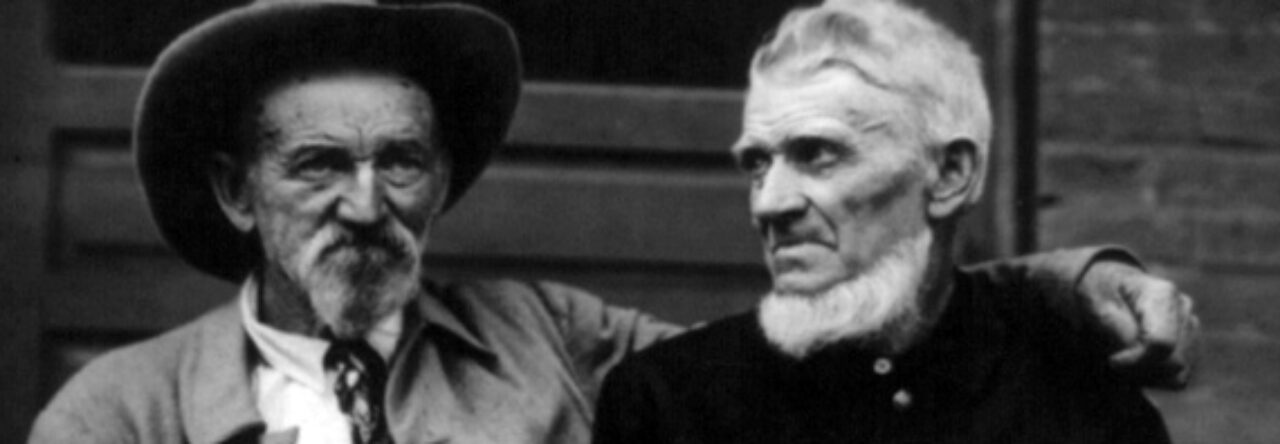

John Cuddy was one of five surviving sons of John and Agnes Cuddy. The Cuddy family owned and operated a distillery in the town. John Taylor also had a sister, Maggie, and two brothers who died as young children.

Sources

Cuddy’s letters from the Civil War are online at Dickinson College’s Their Own Words. You can learn more about these letters in this short essay. In addition, you can read this interactive essay on House Divided’s Journal Divided.

Places to Visit

You can visit the National Park Service’s Andersonville Prison (Camp Sumter), which is located near Andersonville, Georgia. After a tour the historic prison site, visitors can see the the National Prisoner of War Museum and the Andersonville National Cemetery. You can also visit the Florence Stockade and the Florence National Cemetery in Florence, South Carolina.

Images

Leave a Reply