The election of 1860 showed just how frayed the nation’s political system had become after a decade of uninterrupted sectional turmoil, and how unlikely a Henry Clay – style grand compromise would be at the start of the new decade. The campaign had barely gotten underway when John Brown resurfaced by invading the slave state of Virginia and occupying the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry in October, 1859. The raid was over just thirty-six hours after it had begun, and Brown and six of his surviving followers were hastily convicted and sentenced to hang after a sensational trial in Charles Town, Virginia. Harpers Ferry polarized the United States as no previous event ever had, and set in motion a dizzying spiral of actions and reactions. At the start of 1860, the raid and some Northerners’ responses to it threatened to cost the Republican Party at the polls. “ The quicker they hang him and get him out of the way, the better, ” said Republican Charles H. Ray. “ We are damnably exercised here about the effect of Old Brown’s retched fiasco . . . upon the moral health of the Republican Party! ”

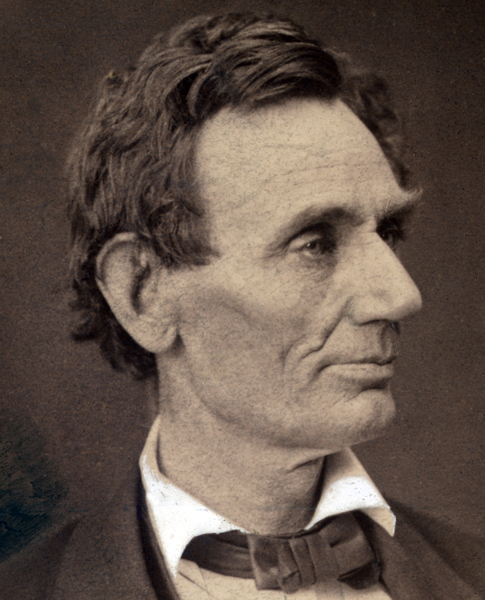

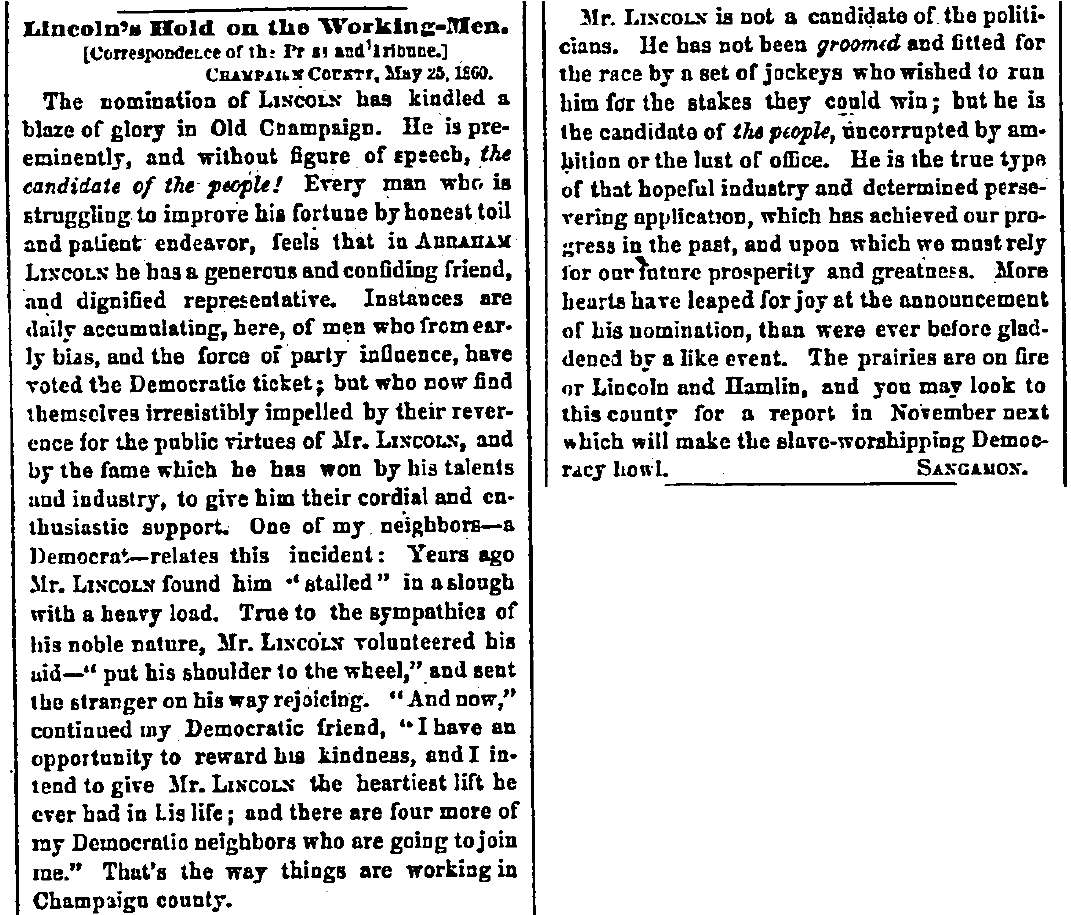

In the South, newspapers declared that Brown’s actions were simply the logical (and inevitable) outcome of Republican agitation over slavery restriction. The Baltimore Sun, heretofore the voice of border state moderation, announced that the South could not afford to “live under a government, the majority of whose subjects or citizens regard John Brown as a martyr and a Christian hero, rather than a murderer and a robber” Time and again, Southern criticism fell on those considered more “radical” opponents of slavery, men like William H. Seward and Horace Greeley. “Brown may be insane,” wrote the editor of the Richmond Enquirer, “but there are other criminals, guilty wretches, who instigated the crime perpetrated at Harpers Ferry ... bring Seward, Greeley, Hale, and Smith to the jurisdiction of Virginia and Brown and his deluded victims in the Charlestown [sic] jail may hope for a pardon.” Suddenly the political futures of Republicans not heretofore known as “radicals,” men like Abraham Lincoln, were looking up.

December 2, 1859

Sidenotes

| Documents | People |

| Major Topics | Sources |