"Refreshment Saloons in Civil War Philadelphia"

by Brenna McKelvey

by Brenna McKelvey

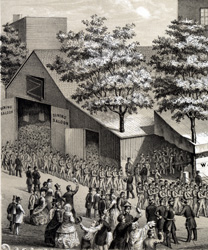

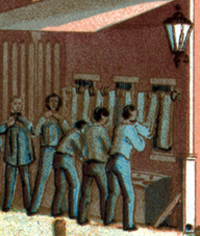

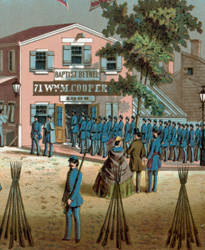

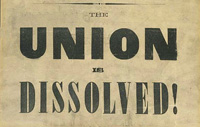

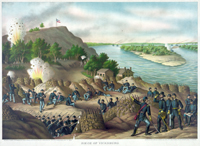

Not all of the heroes of the Civil War fought on the battlefield. In Philadelphia, the volunteer refreshment saloons provided some of the most important service. Northern newspapers praised the city’s saloons which served as safe havens where “the dusty soldier [could] wash off his travel stains.” William M. Cooper, a merchant, was the first to decide that his storefront on Otsego Street should aid Union troops passing through his city. The Cooper Shop Volunteer Refreshment Saloon opened on May 26, 1861. Cooper became the committee’s president and served in this position until the war’s end. The Cooper Shop soon entered into a friendly rivalry with the larger Union Saloon, which opened the same week, but the dramatic individual efforts of the Cooper Shop leaders gave it a special place in the hearts of Philadelphia’s residents. All of these war time establishments proved important as places of rest where soldiers obtained food, drink, places to wash, and even medical care. The saloons helped forge a collective war effort.

"Refreshment Saloons in Civil War Philadelphia" p. 2

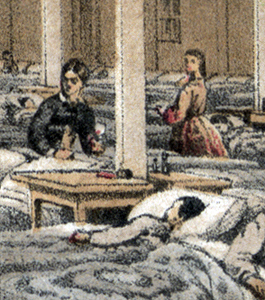

The Cooper Shop Saloon added a second floor hospital in October 1861. Dr. Andrew Nebinger, Jr. received the appointment as the surgeon-in-charge. He agreed to work as a volunteer and did not receive a salary for his service to the wounded soldiers. Admired by many who came into contact with him, Nebinger’s surgical skills received praise from fellow doctors such as C.E. Hill who described the surgeon as one of the finest men he had ever met, saying, “his kindness to the sick, and his untiring zeal for their comfort, proves him to be a philanthropist of the first order…” Others described Nebinger as an expert doctor who possessed great administrative ability and devoted patriotism, which gained him respect among the soldiers and their families.

"Refreshment Saloons in Civil War Philadelphia" p. 3

The soldiers and their families seemed to appreciate the efforts of the Cooper Saloon. After leaving Philadelphia Sergeant N.P. Gale of New York wrote to Cooper, “many a soldier has thought of your kindness.” The refreshment saloon committees provided traveling soldiers with small comforts such as food, drink, and bathing facilities, while the doctors and nurses provided more urgent medical care to those returning from the battlefields. The parents of young soldiers often expressed their gratitude to Nebinger, whose “faithful efforts” and dedication to his patients helped save their sons. According to historian J. Matthew Gallman, the refreshment saloon’s “greatest benevolent contribution cannot be measured by returns on ledger sheets, but by the long hours devoted to sewing clothes, cooking food, and ministering to wounded soldiers.”

"Refreshment Saloons in Civil War Philadelphia" p. 4

Along with Nebinger, Anna M. Ross became a fixture in the lives of Union soldiers at the Cooper Shop Hospital. She played a large role in its management through her appointment as the hospital’s Lady Principal until her death, reportedly from overwork, in 1863. Ross’s patients and coworkers praised her since she showed “energy, perseverance, zeal, and endurance [which] were seen, in combination with tender sensibility, love, and self-sacrifice.” Her dedication to the hospital and its patients made the Cooper Shop Hospital one of the most warmly remembered institutions created in the midst of the Civil War. In one particular instance Ross displayed these fine qualities while tending to a dying lieutenant from New York. According to a history of women’s work during the war, she never left his side and tried to ease his pain by cooling his forehead and offered him support by saying, “call me Anna and tell me all which your heart prompts you to say.”

"Refreshment Saloons in Civil War Philadelphia" p. 5

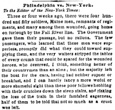

Philadelphia’s citizens rallied around the Cooper Shop by providing about $70,000 during the course of the war, the equivalent of nearly one million dollars today. Also, about 400,000 soldiers passed through the Cooper Shop Volunteer Refreshment Saloon during four years of fighting. The success of these saloons in Philadelphia had an impact on the way people in other places viewed their local relief efforts. A woman from New York complained that her state sent soldiers through without giving them a place to rest while “Philadelphia lets no regiment, of whatever State, whether going to or from battle, pass hungry through her streets.” Soldiers from other states also noted that “anyone who thinks there is any lack of support for the war has only to march through Philadelphia.” The saloon continued dedicating its resources to the Union troops until August 28, 1865 when the 32nd U.S. Colored Troops and the 104th Pennsylvania became the last two regiments served in the Cooper Shop before it closed at noon.

"Refreshment Saloons in Civil War Philadelphia" p. 6

When William Cooper died in poverty in February 1880, various newspapers and the Grand Army of the Republic appealed to former soldiers for donations to support the surviving members of his family. Former soldiers immediately offered to “shoulder the entire indebtedness of the late Mr. Cooper, if they be allowed what they term ‘the humble honor.’” Andrew Nebinger and his family remained an integral part of Philadelphia’s society after the war as leaders in the city’s public school system. According to one history of the public schools, the family left Philadelphia “memories that will long be cherished and honored.” Anna M. Ross embodied the persona created by Pennsylvania women during the Civil War which, according to William Blair and William Pencak, was “imbued with patriotism and loyalty to the country.” She also received unique posthumous recognition from the Grand Army of the Republic as it named Post 94 in Philadelphia after her -- a rare honor for a woman.

"Refreshment Saloons in Civil War Philadelphia" p. 7

Philadelphia made several great contributions to the Union war effort on the home front, including its volunteer refreshment saloons. They began with the charity of William M. Cooper who dedicated his work space to the Union cause. Dr. Andrew Nebinger held a special place in the hearts of the soldier’s families because he cared for sick and wounded men without demanding pay while Anna M. Ross left an unforgettable legacy as she worked herself to death while caring for the soldiers. Their stories illustrated how the citizens of Philadelphia provided humanity in a time of bloodshed and left a tremendous impact on the home front efforts during the Civil War. The New York Times noted the importance of the refreshment saloons, “even though the individual benefactions were small, they were invaluable; and have caused the greater part of the Union army to entertain a kind and grateful feeling for Philadelphia.”