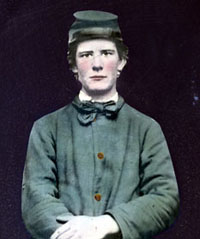

Carlisle to Andersonville: The Story of John Taylor Cuddy

by John Osborne

by John Osborne

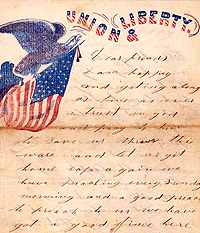

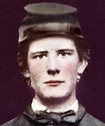

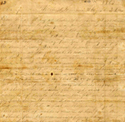

At the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, sixteen year old Pennsylvania farm boy John Cuddy took immediate action to help preserve the Union when he enlisted in one of the four companies of volunteers raised in nearby Carlisle. Three and a half years of training, battle, capture, and imprisonment were to follow. We know about this obscure young soldier thanks to the preservation of seventy-seven letters he wrote in regular but untutored style to his family and friends from the various places he served with his regiment. These take the reader through the rigor of training, the boredom of camp, the wonder of new places in young eyes, and the thrill, exhaustion, and ultimate disillusion of deadly encounters on the battlefields of Maryland and Virginia.

“From Carlisle to Andersonville” p. 2

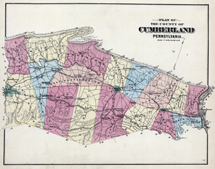

John Taylor Cuddy was born on October 17, 1844 in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania where his father owned a farm in North Middleton Township. As was common in central Pennsylvania, the farm had a distillery attached where corn was converted to spirits. The young Cuddy completed only a few years of elementary schooling before he apprenticed with his father. He was a farm hand and a distiller before he had entered his teens. Like thousands of other ordinary and young Pennsylvanians in the spring of 1861, Cuddy was taken with the excitement of war and the President’s call for volunteers to protect the Union. Days after the firing on Fort Sumner, local lawyer Robert Henderson began to raise a volunteer unit called the Carlisle Fencibles. Adding a year to his age to avoid any complications, Cuddy joined up.

“From Carlisle to Andersonville” p. 3

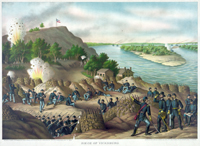

After a delay of some weeks spent drilling in Carlisle, the Fencibles became Company A, of the 7th Pennsylvania Reserve Corps (36th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry) and Cuddy was officially mustered in as a private for a three year enlistment on June 5, 1861. The regiment trained at Camp Wayne in West Chester near Philadelphia and then joined the defense of Washington. After an extended period in camp, the war began in earnest for the men of the 36th Pennsylvania in June 1862, when the regiment was heavily engaged around Gaine’s Mill and Mechanicsville, Virginia and suffered heavy casualties. Cuddy’s response in letters home was one of relief and confidence that if he could survive such encounters, he could come home unscathed. Action continued in September at Antietam, where the unit suffered heavy casualties although Cuddy may have been on leave when it was fought. He did participate in the brave but futile and costly defeat at Fredericksburg in December.

“From Carlisle to Andersonville” p. 4

Progressively, in untutored grammar and with wretched spelling, Cuddy’s letters home showed a bold new recruit determined to teach the rebels a lesson, a relieved and sober survivor of battle, and a weary and disillusioned veteran counting the days to the end of his three year enlistment. He was particularly dismayed with Lincoln’s January 1863 Emancipation Proclamation when he echoed in a letter to his family a common response in the Army that now “the rebels is fighting for there rites.” In April 1864, with most of the regiment tantalizingly close to the end of their time of service, Cuddy’s unit joined in the Battle of the Wilderness. There, all 272 officers and men, including the thirty-three survivors of Company A, were cut off, surrounded, and captured. There would be no more letters home from young Cuddy.

“From Carlisle to Andersonville” p. 5

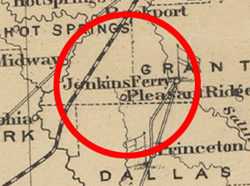

He and his comrades were sent by train to Georgia and imprisoned at the notorious Andersonville prison. Sixty-seven men of the regiment died over the next months in the horrendous conditions of the open camp. Cuddy survived Andersonville but when he and his fellows were transferred to the equally harsh new camp at Florence, South Carolina in September 1864, the young soldier’s shattered health gave way. John Taylor Cuddy died of malnutrition and sickness in Florence on September 29, 1864, eighteen days before his twentieth birthday. His letters do remain, however, to preserve the memory of one young Union infantryman and provide for us a priceless window into the experience of citizen soldiers in the American Civil War.