“Why Lincoln Won in 1860”

by Michael Burlingame

by Michael Burlingame

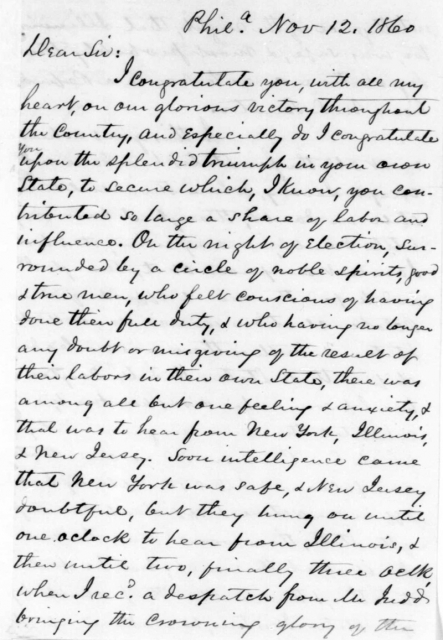

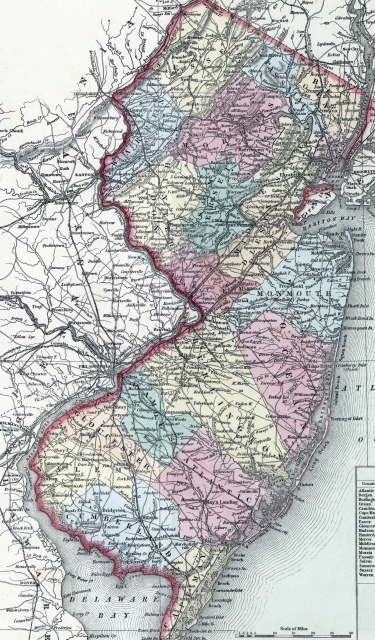

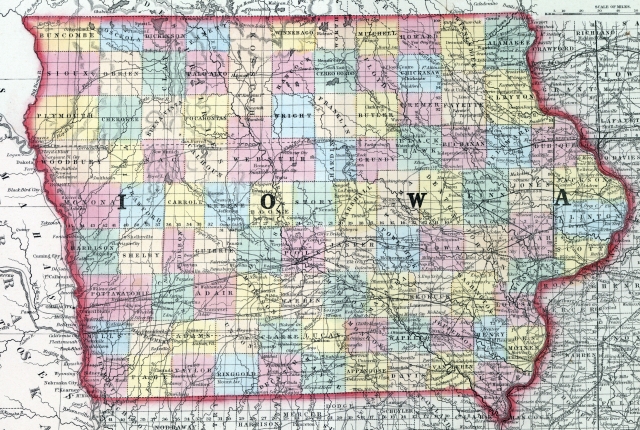

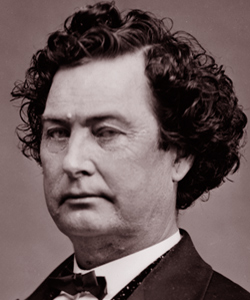

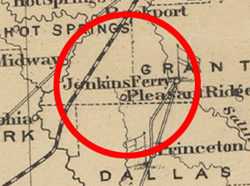

Although Lincoln won only 39.9% of the popular vote (far more than the 29% which the runner-up, Douglas, received), he took a solid majority of the electoral votes, 180 out of 303. He carried all the Free States except New Jersey, where the Bell, Breckinridge, and Douglas forces created a fusion ticket at the last moment and took 52.1% of the ballots cast. But because some anti-Lincoln voters refused to go for the fusion slate, the Republicans received four of the state’s seven electoral votes. According to John Bigelow, “That little State, the property of a railroad company [the Camden and Amboy] which runs through it and twirls it around like a Skewer[,] voted against him because it has the misfortune to be inhabited by two men, each of whom wished to be Secretary of the Navy and hoped by making the State look insecure, to get an offer of terms.” Those men were William L. Dayton and William Pennington, former speaker of the U.S. House. Their lackluster support of the ticket was widely criticized.

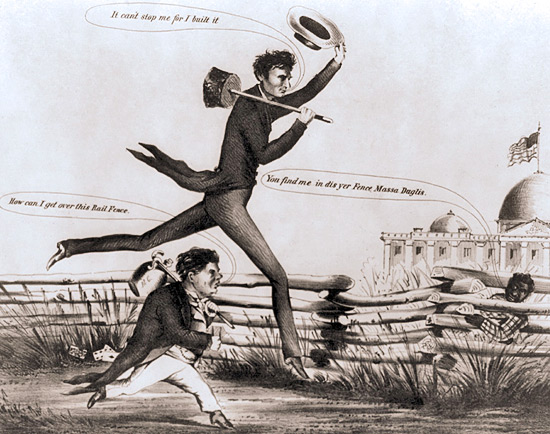

Cartoon, December 1860

Sidenotes

| Documents | Places |

| Major Topics | Sources |

| People |

“Why Lincoln Won in 1860” p. 2

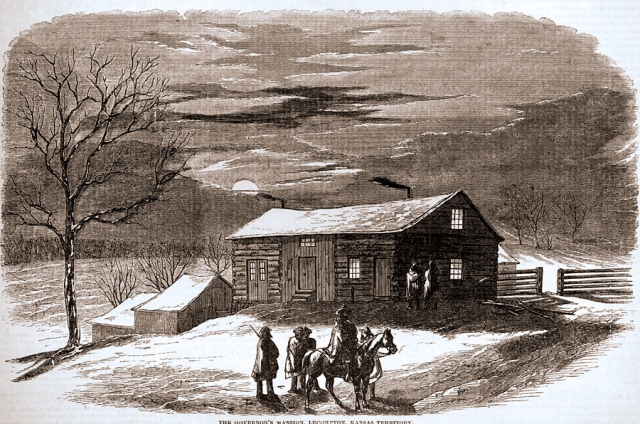

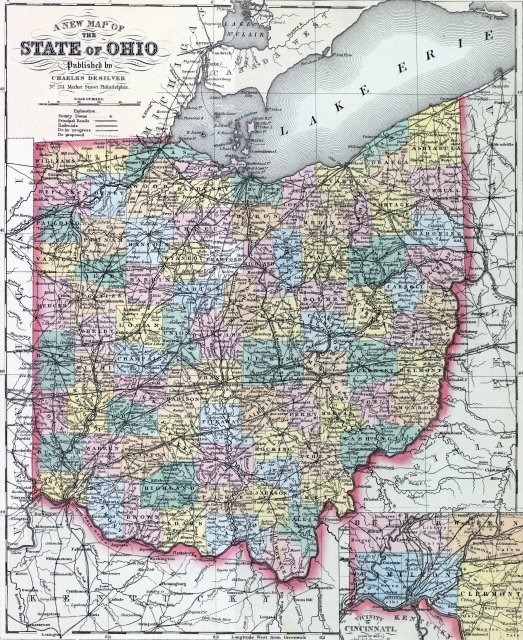

The Republicans triumphed because of their party’s unity and the bitter split within the Democracy; because of the rapidly growing antislavery feeling in the North, where the Lecompton Constitution and the Dred Scott decision outraged many who had not voted Republican in 1856; because of the North’s ever-intensifying resentment of what it perceived as Southern arrogance, high-handedness, and bullying; because Germans defected from the Democratic ranks; because the Republican economic program appealed both to farmers (with homestead legislation) and to manufacturers and workers (with tariffs) far more than the Democratic economic policies adopted in response to the Panic of 1857; because the rapidly improving economy blunted fears of businessmen as they contemplated a Republican victory; and because of public disgust at the corruption of Democrats, most notably those in the Buchanan administration. Lincoln did especially well among younger voters, newly eligible voters, former nonvoters, rural residents, skilled laborers, members of the middle class, German Protestants, evangelical Protestants, native-born Americans, and most especially former Know Nothings and Whig-Americans.

'Handwriting on the Wall'”

Cartoon, 1860

Sidenotes

| Events | People |

| Major Topics | Sources |

“Why Lincoln Won in 1860” p. 3

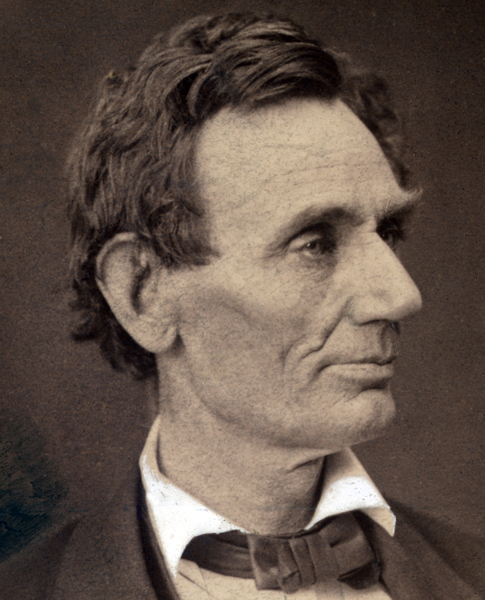

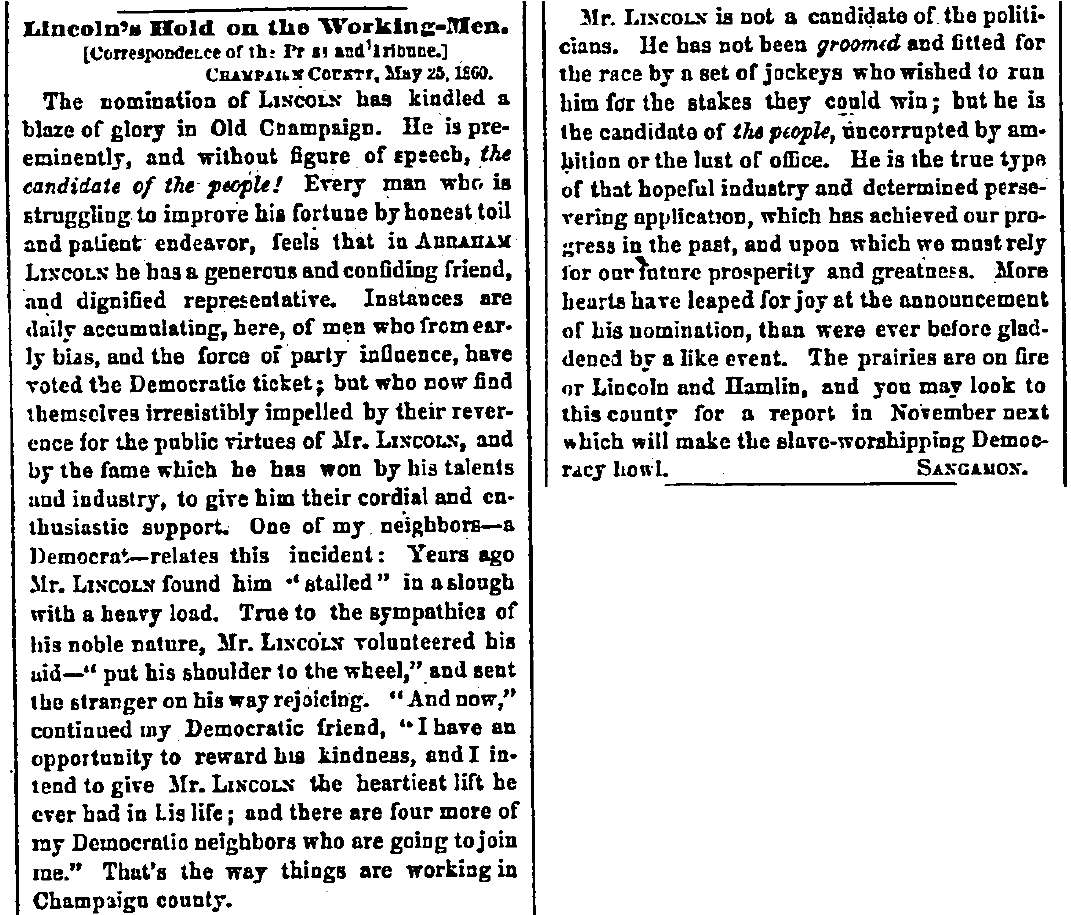

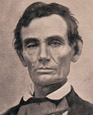

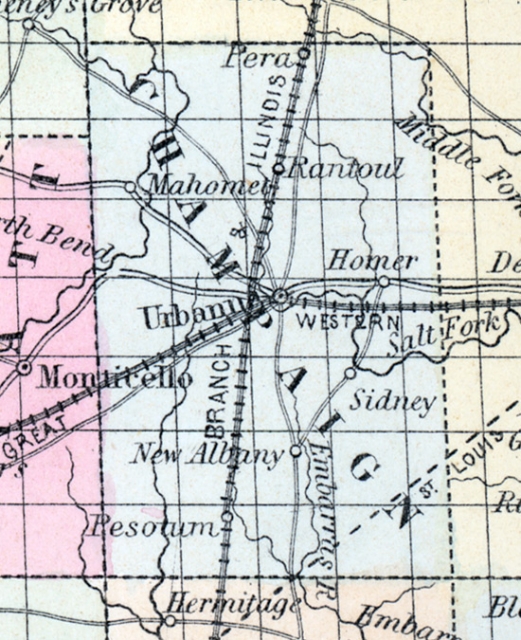

In the absence of opinion surveys and exit polls, it is difficult to say with precision why these groups were more likely to vote Republican than Democratic or Constitutional Unionist. Correspondence, newspaper commentary, and other anecdotal sources suggest that Lincoln’s victory was in part due to his character, biography, and public record. In July, John A. Kasson reported from Iowa: “I never talk to an audience of farmers without noticing the intense interest as they listen to the story of his early life & trials in making himself what he is, – the ablest & most eminent man in the West.” An Ohio farmer praised Lincoln as “a self-made man, who came up a-foot. We like his tact – we like his argumentative powers – we like his logic, and we like the whole man.” A resident of Champaign, Illinois, wrote that “[e]very man who is struggling to improve his fortune by honest toil and patient endeavor, feels that in Abraham Lincoln he has a generous and confiding friend, and dignified representative. Instances are daily accumulating, here, of men who from early bias, and the force of party influence, have voted the Democratic ticket; but who now find themselves irresistibly impelled by their reverence for the public virtues of Mr. Lincoln.”

Inauguration of Abraham Lincoln

Sidenotes

| Documents | Places |

| Major Topics | Sources |

| People |

“Why Lincoln Won in 1860” p. 4

Another Sucker denied that “honest Old Abe Lincoln” thought “a nig[g]er is as good as a poor man” and insisted that the candidate “is a working man” who “respects the poor man a good deal more than drunken old Stephen A Douglas or any of the democratic clicque.” On the stump, Henry S. Lane of Indiana called Lincoln “an apt illustration of our free institutions.” This “obscure child of labor spent a large portion of his life in the humble vocation of farm laborer, and when I look over this vast assembly, composed in part of young men, my heart grows stronger and my hope grows brighter. There listens to me, perhaps, this day, some honest son of toil who will yet reach the . . . position of President.” Frank Blair claimed that by choosing a candidate with such a humble background, Republicans demonstrated “that their hearts are with the people.” Lincoln “is the representative of the great idea of the Republican party – labor – free labor,” Richard Yates told a crowd at Springfield “The poor boy . . . can point to Abraham Lincoln, and straighten himself up and say, ‘I have the same right and same opportunity to be President as any other boy.’”