“Railsplitter”

by Michael Burlingame

by Michael Burlingame

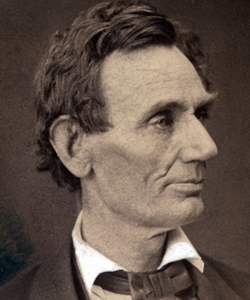

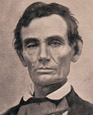

Shortly after the [1860 Illinois Republican] convention opened, the “tall, massive, handsome” Richard J. Oglesby, a rising political star from Decatur, interrupted the proceedings by announcing: “I am informed that a distinguished citizen of Illinois, and one of whom Illinois ever delight to honor, is present.” The 3000 auditors in the makeshift 900-seat convention center impatiently waited for this man to be identified. When Oglesby finally shouted, “Abraham Lincoln,” the crowd roared its approval and tried to jam Lincoln, who had been sitting in the rear of the hall, through the densely packed crowd to the stage. Frustrated by their failure to penetrate the throng, they hoisted him up and passed him “kicking scrambling – crawling – upon the sea of heads between him and the Stand.” When he reached that destination, half a dozen delegates set him upright. “The cheering,” reported an observer, “was like the roar of the sea. Hats were thrown up by the Chicago delegation, as if hats were no longer useful.” Lincoln, who “rose bowing and blushing,” appeared to be “one of the most diffident and worst plagued men I ever saw.” With a smile, he thanked the crowd for its expression of esteem.

“Railsplitter” p. 2

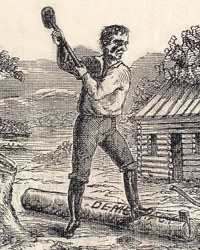

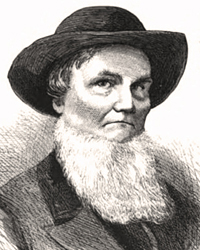

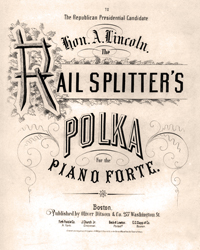

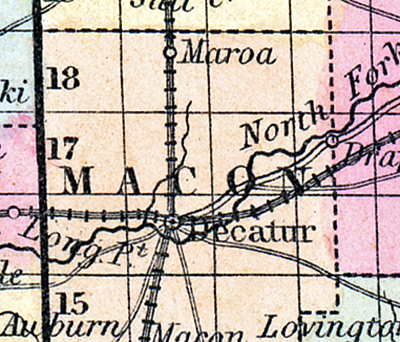

After the aspirants for governor had been placed in nomination but before the voting began, Ogelsby once again interrupted, announcing that “an old Democrat of Macon county . . . desired to make a contribution to the Convention.” The crowd yelled, “Receive it!” Thereupon Lincoln’s second cousin, John Hanks, accompanied by his friend Isaac D. Jennings, entered the hall bearing two fence rails along with a placard identifying them thus: “Abraham Lincoln, The Rail Candidate for President in 1860. Two rails from a lot of 3,000 made in 1830 by Thos. Hanks and Abe Lincoln – whose father was the first pioneer of Macon County.” (The sign painter was wrong about Hanks’s first name and about Thomas Lincoln’s status as an early settler in Illinois.) Oglesby’s carefully staged theatrical gesture, conjuring up images of the 1840 log-cabin-and-cider campaign, electrified the crowd. In response to those thunderous outbursts and calls of “Lincoln,” the candidate-to-be rose, “looking a little sheepish,” examined the rails, then told the crowd…that the rails may have been hewn by him, “but whether they were or not, he had mauled many and many better ones since he had grown to manhood.”

“Railsplitter” p. 3

(Another witness recalled Lincoln’s words slightly differently: “My old friend here, John Hanks, will remember I used to shirk splitting all the hard cuts. But if those two are honey locust rails, I have no doubt I cut and split them.”) Once again the crowd cheered Lincoln, whose sobriquet “the rail-splitter” was born that day. According to Noah Brooks, Lincoln “was not greatly pleased with the rail incident,” for he disapproved of “stage tricks.” Still, Lincoln was rather proud of his rail-splitting talent. Brooks reported that while visiting Union troops at the front in 1863, Lincoln noticed trees that they had chopped down. Scrutinizing the stumps, he said: “That’s a good job of felling; they have got some good axemen in this army, I see.” When Brooks asked about his expertise in rail splitting, the president replied: “I am not a bit anxious about my reputation in that line of business; but if there is any thing in this world that I am a judge of, it is of good felling of timber.” He “explained minutely how a good job differed from a poor one, giving illustrations from the ugly stumps on either side.”

“Railsplitter” p. 4

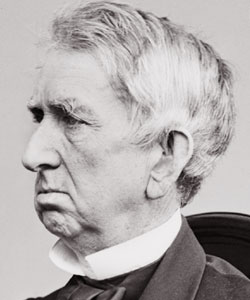

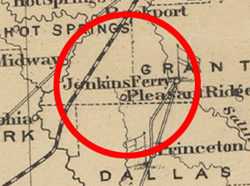

A few days before the Decatur Convention met, Oglesby, who had been seeking ways to emphasize Lincoln’s humble origins (to justify something like Henry Clay’s cognomen, “the mill boy of the slashes”) had asked Hanks what Lincoln had been good at as a young settler in Illinois. “Well, not much of any kind but dreaming,” replied Hanks, “but he did help me split a lot of rails when we made a clearing twelve miles west of here.” Intrigued, Oglesby urged Hanks to show him the spot. They rode out, identified some rails that Lincoln and Hanks may have split three decades earlier, and carried away two of them. When Oglesby proposed to some friends that the rails be introduced at the Decatur convention, they told him to go ahead, for it could do no harm and might do some good. He was not the only Illinois Republican to think the rail splitter image would help Lincoln. In March, Nathan M. Knapp had told a friend: “I want Abe to run; then I want a picture of him splitting rails on the Sangamon Bottom, with 50 cts per hundred marked on a chip placed in the fork of a tree nearby. I think it will win.”

“Railsplitter” p. 5

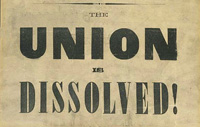

It is not entirely clear if Lincoln was surprised by the appearance of the rails. Oglesby allegedly reported that Lincoln “hunted up the rails himself, tied them together, and made sure they were ready for that scene in the convention.” The delegates may also have been prepared for the presentation of the rails; the Illinois State Journal had a day earlier informed readers that “[a]mong the sights which will greet your eyes will be a lot of rails, mauled . . . thirty years ago, by old Abe Lincoln and John Hanks.” After the ovations for Lincoln, George Schneider, an ardent Seward supporter, presciently remarked that his favorite “has lost the Illinois delegation.”