“That Presidential Grub”

by Michael Burlingame

by Michael Burlingame

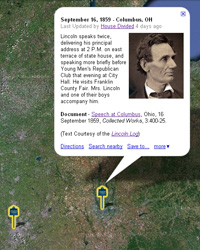

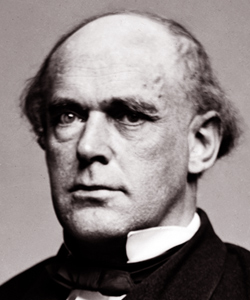

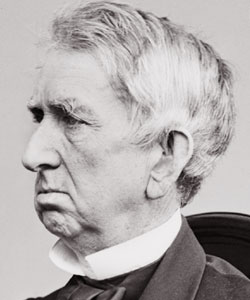

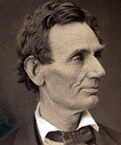

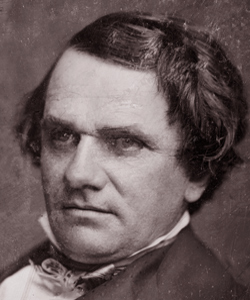

“No man knows, when that Presidential grub gets to gnawing at him, just how deep in it will get until he has tried it,” Lincoln remarked in 1863. That grub began seriously gnawing at him after the 1858 campaign. His astute friend Joseph Gillespie believed that the debates with Douglas “first inspired him with the idea that he was above the average of mankind.” That was probably true, though Lincoln pooh-poohed any talk of the presidency, telling a journalist during the canvass with the Little Giant: “Mary insists . . . that I am going to be Senator and President of the United States, too.” Then, “shaking all over with mirth at his wife’s ambition,” he exclaimed: “Just think of such a sucker as me as President!” In December, when his friend and ally Jesse W. Fell urged him to seek the Republican presidential nomination, he replied: “Oh, Fell, what’s the use of talking of me for the presidency, whilst we have such men as Seward, Chase and others, who are so much better known to the people, and whose names are so intimately associated with the principles of the Republican party.”

“That Presidential Grub” p. 2

When Fell persisted, arguing that Lincoln was more electable than Seward, Chase, and the other potential candidates being discussed, Lincoln agreed: “I admit the force of much of what you say, and admit that I am ambitious, and would like to be President. I am not insensible to the compliment you pay me . . . but there is no such good luck in store of me as the presidency.” The following spring, when Republican editors planned to endorse him for president, he balked. “I must, in candor, say I do not think myself fit for the Presidency,” he said. “I certainly am flattered, and gratified, that some partial friends think of me in that connection; but I really think it best for our cause that no concerted effort . . . should be made.” When William W. Danenhower told Lincoln that his name was being seriously considered by Republican leaders for the presidency, he laughingly replied: “Why, Danenhower, this shows how political parties are degenerating, you and I can remember when we thought no one was fit for the Presidency but ‘Young Harry of the West,’ [i.e., Henry Clay] and now you seem to be seriously considering me for that position. It’s absurd.”

“That Presidential Grub” p. 3

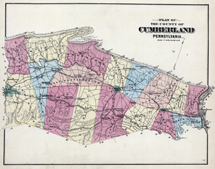

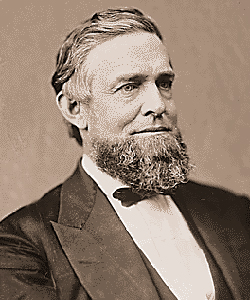

But it was not absurd, for the race for the nomination was wide open. Seward seemed to be the front runner, but many thought him as unelectable as Chase. Other names being tossed about – John McLean, Nathaniel P. Banks, Edward Bates, Lyman Trumbull, Jacob Collamer, Benjamin F. Wade, Henry Wilson – were all long shots at best. As Schuyler Colfax noted in December 1858, “there is no serious talk of any one.” Despite his modesty, Lincoln between August 1859 and March 1860 positioned himself for a presidential run by giving speeches and corresponding with party leaders in several states, among them Iowa, Ohio, Wisconsin, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Kansas. At the same time, he labored to keep Republicans true to their principles by having them steer a middle course between the Scylla of Douglas’s popular sovereignty and the Charybdis of radical abolitionism. Only thus could he and his party capture the White House. And only thus could a lesser-known Moderate like himself lead the ticket.

Lincoln’s Campaign for the 1860 Nomination

Sidenotes

| Major Topics | Places |

| People | Sources |

“That Presidential Grub” p. 4

Lincoln took encouragement from the ever-widening rift in the Democratic party over such issues as a federal slave code for the territories and the reopening of the African slave trade. To Herndon and others he said, in substance: “an explosion must come in the near future. Douglas is a great man in his way and has quite unlimited power over the great mass of his party, especially in the North. If he goes to the Charleston Convention [of the national Democratic party in 1860], which he will do, he, in a kind of spirit of revenge, will split the Convention wide open and give it the devil; & right here is our future success or rather the glad hope of it.” Herndon recalled that Lincoln “prayed for this state of affairs,” for “he saw in it his opportunity and wisely played his line.”