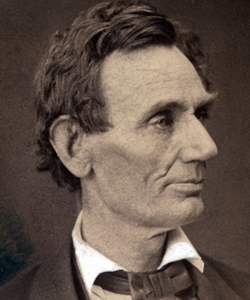

“Honest Abe”

by Michael Burlingame

by Michael Burlingame

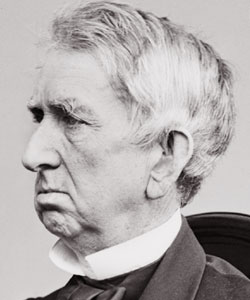

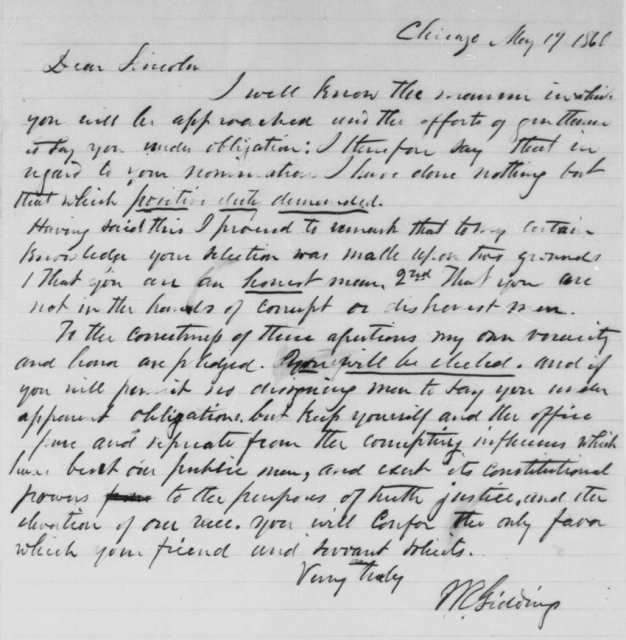

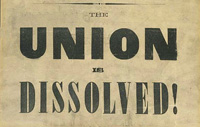

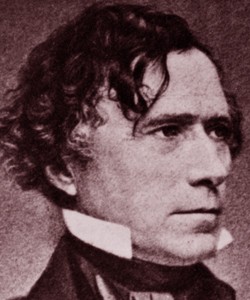

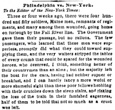

Shortly after the 1860 Chicago Convention, Joshua Giddings assured Lincoln that “your selection was made upon two grounds,” first that “you are an honest man,” and second that “you are not in the hands of corrupt or dishonest men.” Seward suffered by contrast, and some of the senator’s backers acknowledged that they “must not blame the people of the United States for being afraid that the election of a leading New York politician to the Presidency would only displace the existing corruption at Washington by a new importation of venality and political knavery from Albany.” A New York delegate acknowledged that all the forces working against Seward would have been insufficient to defeat him “had not his opponents strengthened their arguments by allusion to the corruptions practiced at Albany during the past winter. No man entertained the idea that Mr Seward was connected with them, but it was charged that his friends were.” Hostility to corruption not only led to Lincoln’s nomination, it also helped assure his victory in one of the most crucial elections in American history. The public was fed up with steamship lobbies, land-grant bribery, hireling journalists

“Honest Abe” p. 2

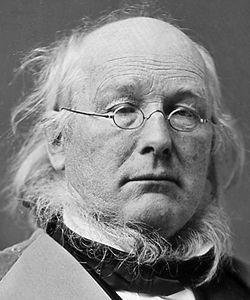

the spoils system, rigged political conventions, and cost overruns on government projects. At a New York ratification meeting, Horace Greeley introduced a resolution proclaiming that there were two irrepressible conflicts, one pitting freedom against “aggressive, all-grasping Slavery propagandism” and the other, “not less vital,” between “frugal government and honest administration” on the one hand and “wholesale executive corruption, and speculative jobbery” on the other. Samuel Bowles of the Springfield, Massachusetts, Republican accurately prophesied that on “an issue likely to rival, if not to overshadow, that of the irrepressible negro – that of honesty, simplicity and economy in public affairs,” Lincoln would run well, for he “is a man of the most incorruptible integrity” whose forte is honesty.” Along with several other newspapers, the Cincinnati Commercial lauded the candidate as a “straight- out and decided Republican” whose “administration of the government would be honest, economical and capable.” William Cullen Bryant pledged that his New York Evening Post would “do all it could” to “turn out the present most corrupt of administrations, and install an honest administration in its stead.”

“Honest Abe” p. 3

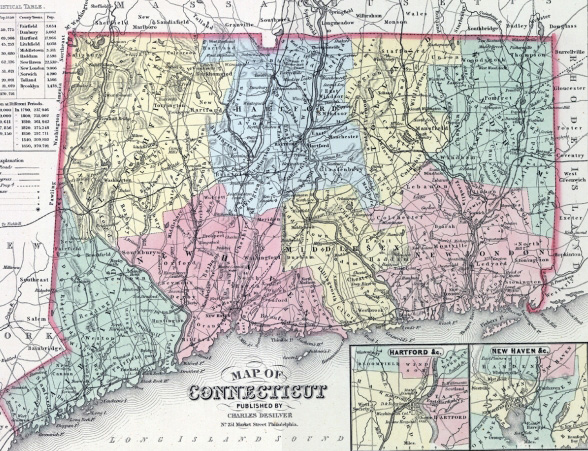

New Englanders stressed the corruption issue. The Concord New Hampshire Statesman argued that Lincoln’s lack of national political experience was “an element of strength,” for it meant that he had not succumbed “to the gross corruptions so prevalent in Washington.” The nation “is suffering for want of an incorruptible Chief Magistrate… A change cannot be for the worse, and may be for the better; then let us have a change.” In Connecticut, the Hartford Courant declared that “[o]ne of the strongest arguments in favor of the election of Lincoln to the Presidency is his HONESTY” and “old-fashioned integrity and firmness.” The people “all want the government administrated with integrity and economy. We have tried two dishonest Administrations of the Democratic party. Let us try them no longer, but place the government in the hands of uncorrupted and uncorruptible men.” After winning the presidency, Lincoln told a visitor: “All through the campaign my friends have been calling me ‘Honest Old Abe,’ and I have been elected mainly on that cry.” His reputation as an honest man was as important as his reputation as a foe of slavery.