"Lincoln and Know Nothings"

by Michael Burlingame

by Michael Burlingame

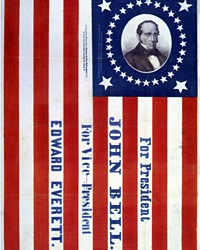

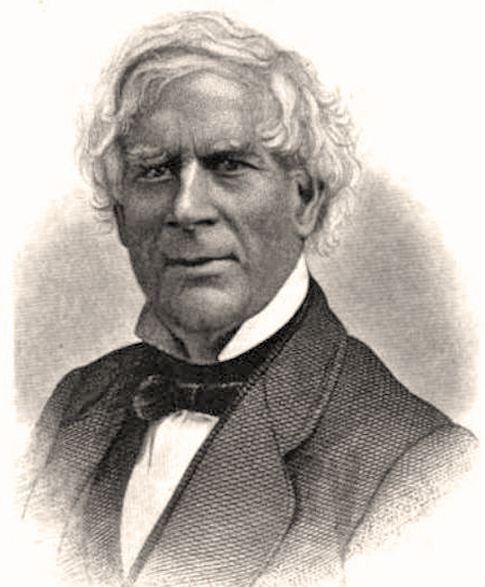

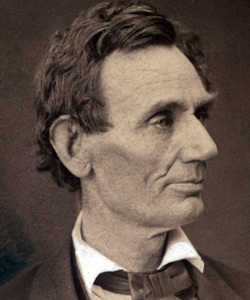

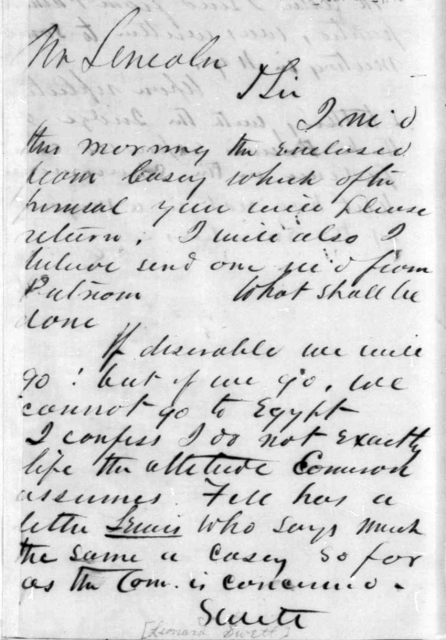

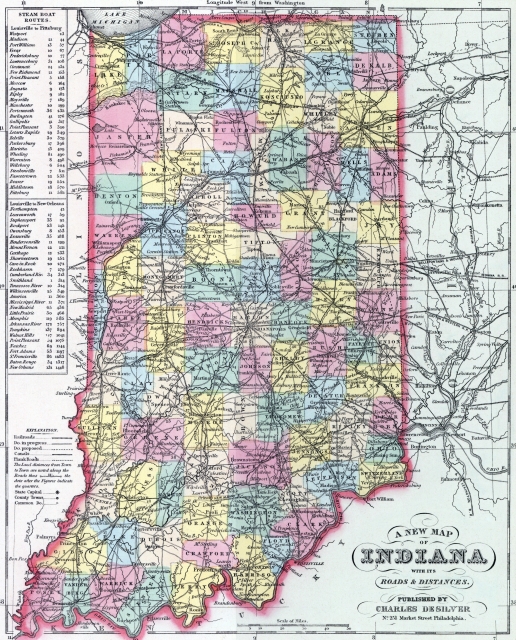

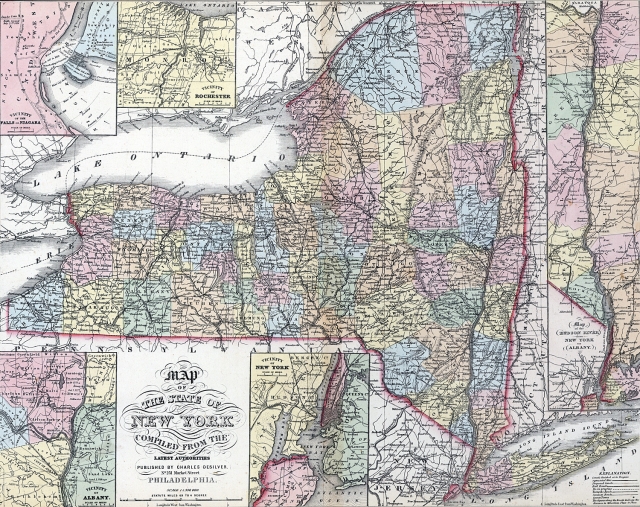

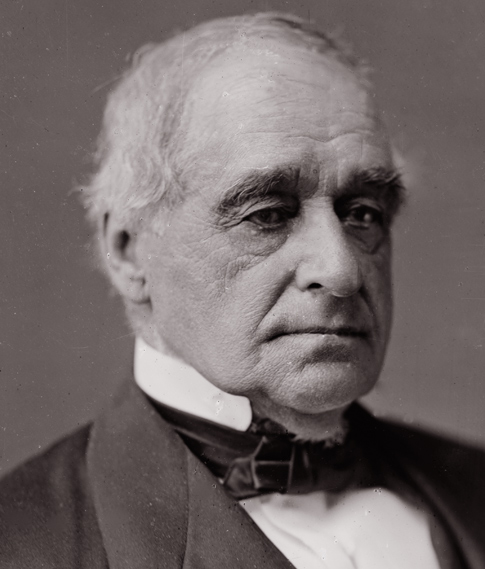

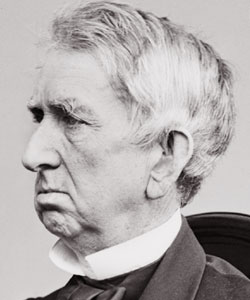

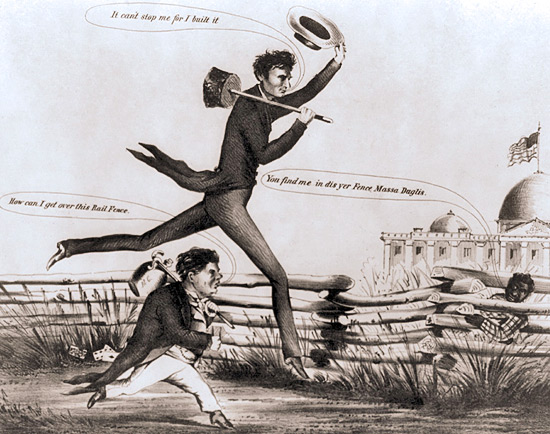

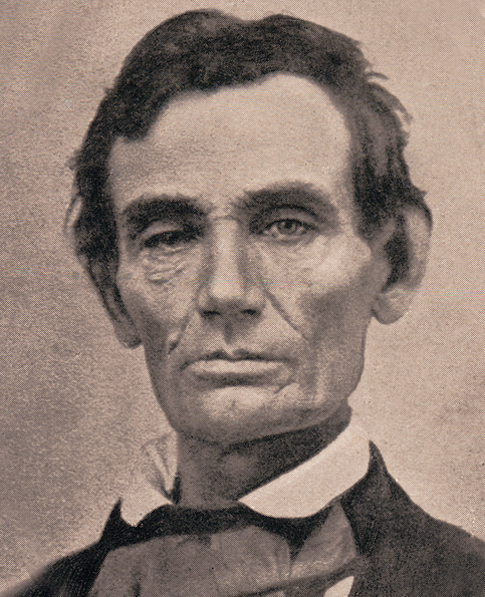

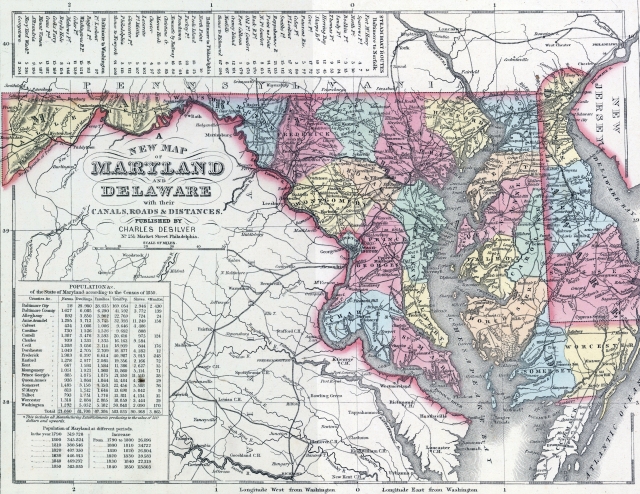

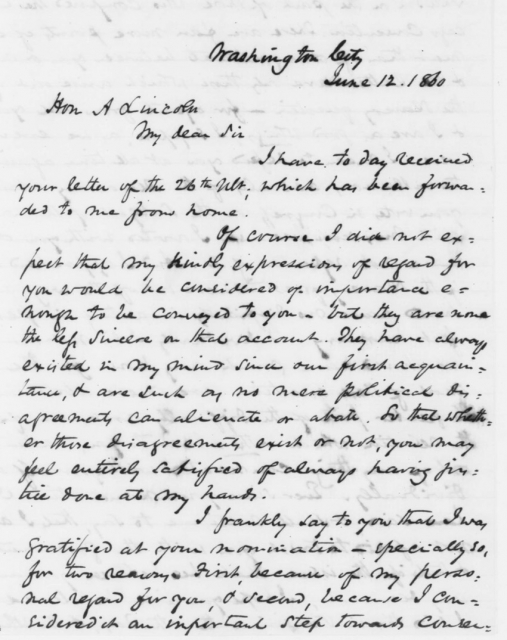

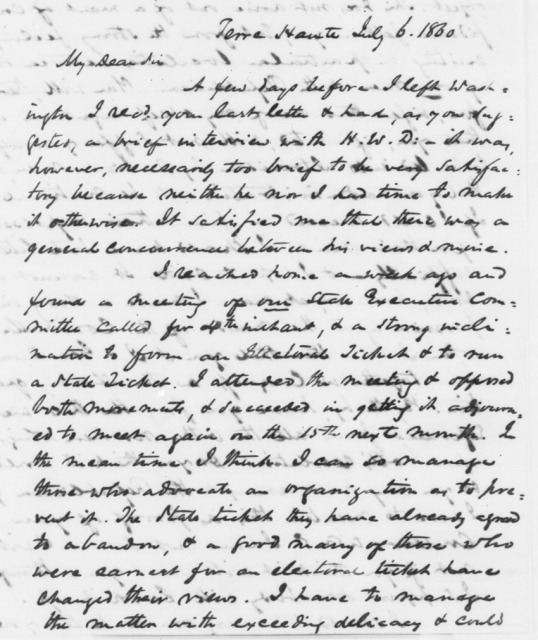

The [1860] election hinged on the Fillmore voters of 1856, especially in Indiana and Pennsylvania, where gubernatorial contests were to be held in October, and also in New York. Lincoln realized that he must win over men like “the great high priest of Knownothinigism,” James O. Putnam, the postmaster at Buffalo and a close friend of Millard Fillmore. Putnam, said Lincoln, resembled Weed: “these men ask for just, the same thing – fairness, and fairness only.” In time Putnam came to admire Lincoln vastly, calling him “one of the most remarkable speakers of English, living.” As for [John] Bell, Putnam acknowledged that the Tennesseean “has the respect and confidence of every man of American antecedents, but of what earthly service can 20,000 or 30,000 votes be to him in New York?” Putnam deserted the Bell forces because “he saw no chance for them to carry the Northern States, and his only hope in defeating the Democratic party, and thereby promoting the interests of the country, was in a union with the Republicans upon the Chicago platform and nominees.” (As president, Lincoln was to name Putnam consul at Le Havre.)

"Lincoln and Know Nothings" p. 2

In Putnam’s hometown of Buffalo, the leading American party newspaper praised Lincoln for qualities lacking in the corrupt Republican legislature at Albany. “Mr. Lincoln’s nomination . . . guarantees executive honesty. It assures us that no bargains have been made, no greedy disposition of the spoils already accomplished. His principles are our principles. We only differ from Republicans in the relative importance attached to the Slavery issue and in having perhaps a larger faith in the final triumph of the right. Thus holding, thus satisfied of the honesty of the party with which we act, we are unreserved in our support of Lincoln and Hamlin.” Commenting on this endorsement, Washington Hunt, a leading conservative, said that the editor’s view of Lincoln, “unsound and fallacious as it is, operates upon many persons who are disposed to follow the current and take refuge in what they consider a strong and prosperous party.” Other American party members shared the belief that voting for Bell would be futile, while electing Lincoln would rebuke the hated Democrats. The Know Nothings were “so jubilant over the defeat of Seward that all go in for the ticket,” noted another Buffalo Republican.

"Lincoln and Know Nothings" p. 3

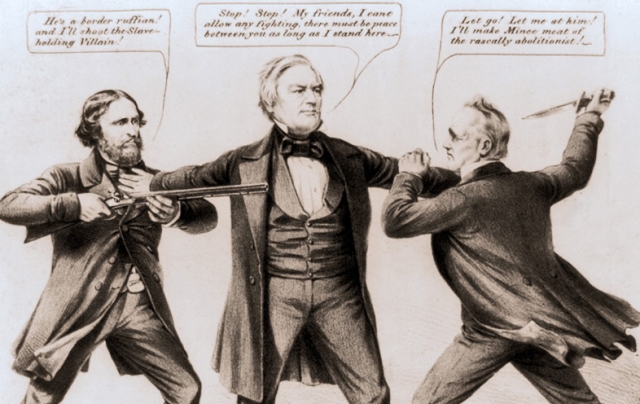

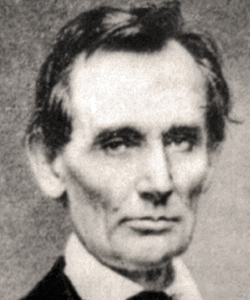

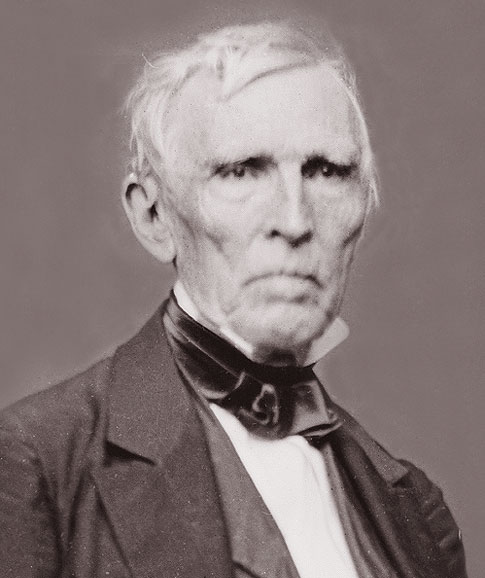

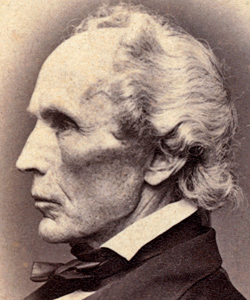

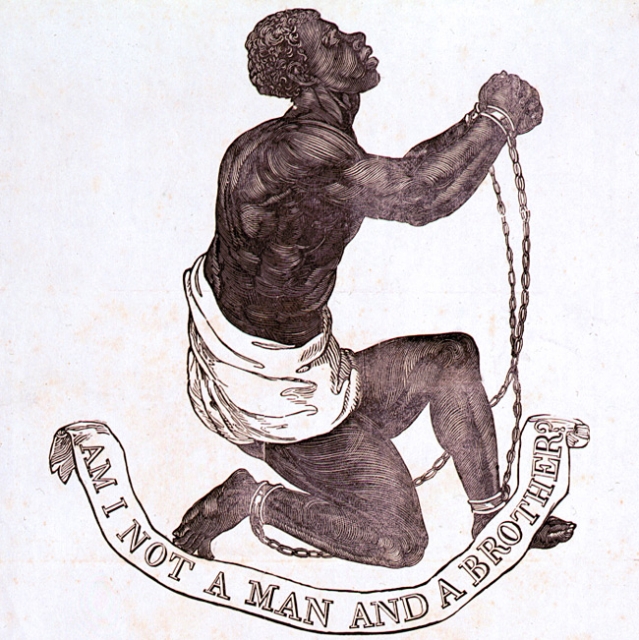

Lincoln was disappointed by the opposition of John J. Crittenden, who warned that although the Republican nominee was “an honest, worthy and patriotic man,” nevertheless as “the Republicans’ President” he “would be at least a terror to the South.” A former congressman (and future senator) from the Blue Grass State, Garrett Davis, called Lincoln “an honest man of fair ability” but found him unacceptable because “for some years past he has been possessed of but one idea – hostility to slavery.” Another American party leader who needed to be cultivated was David Davis’s cousin, Congressman Henry Winter Davis of Maryland, who was so influential that the committee of twelve at the Chicago Convention had asked him to run for vice president. He declined lest his candidacy ruin the ticket in the Northwest. Like many other Know Nothings, he objected to the Republican platform’s “supremely foolish” plank denouncing “any change in our naturalization laws or any state legislation by which the rights of citizenship hitherto accorded to immigrants from foreign lands shall be abridged or impaired” and favoring “a full and efficient protection to the rights of all classes of citizens.”

"Lincoln and Know Nothings" p. 4

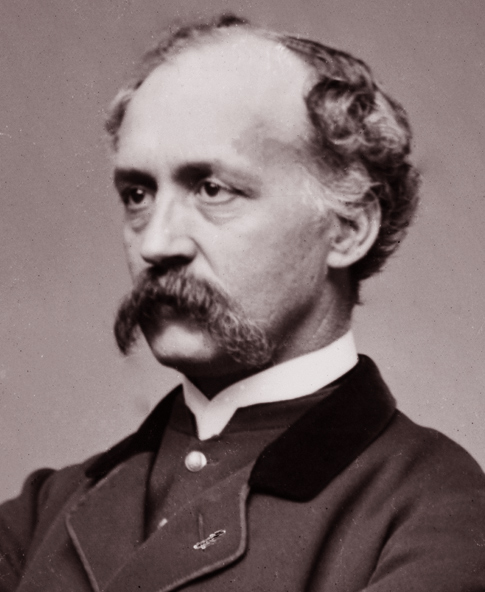

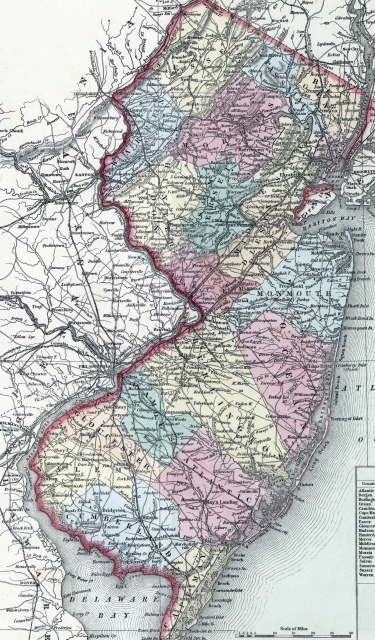

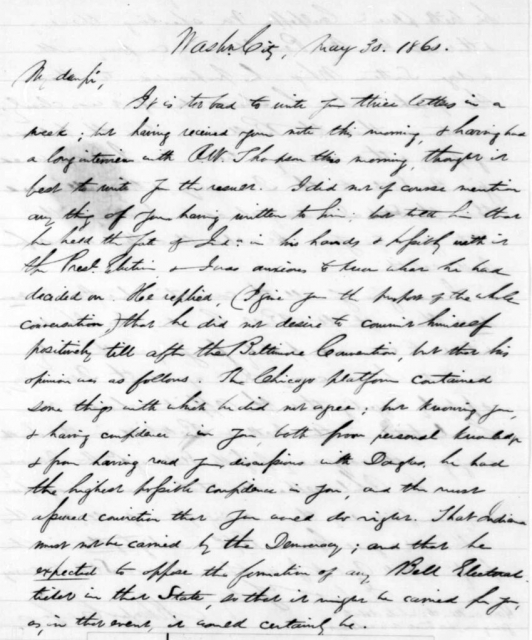

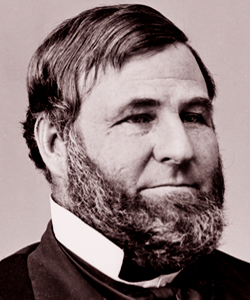

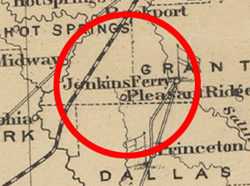

Since the term “Republican” was poison in Maryland, Davis said he would support Bell there but hinted that he might be willing to stump for Lincoln in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. He thought “the Chicago nomination a wise one,” for the candidate was “long headed.” Davis’s only fear was that Seward would be named secretary of state and act as “a weight on the administration.” Though he disliked Bell’s pro-slavery public letter, he believed a Bell administration “would be the same as Lincoln[’]s or Mr. [Henry] Clay[’]s.” Lincoln urged Richard W. Thompson, his friend from their days together in Congress and a leader of Indiana’s Constitutional Union party, to “converse freely” with Davis. Thompson did so. He also told Lincoln while he himself might not vote Republican, he would work to block a Bell ticket in Indiana. (In 1856, Thompson had badly damaged Republicans’ chances in the Hoosier state by thwarting their attempts to fuse with the Americans; in return he received a rich reward from the Democrats.)

"Lincoln and Know Nothings" p. 5

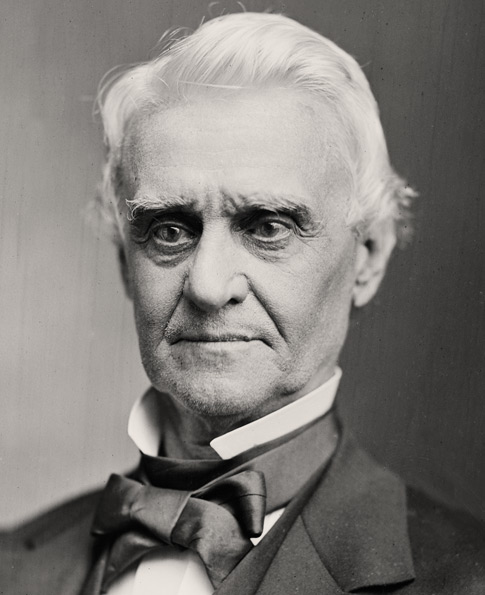

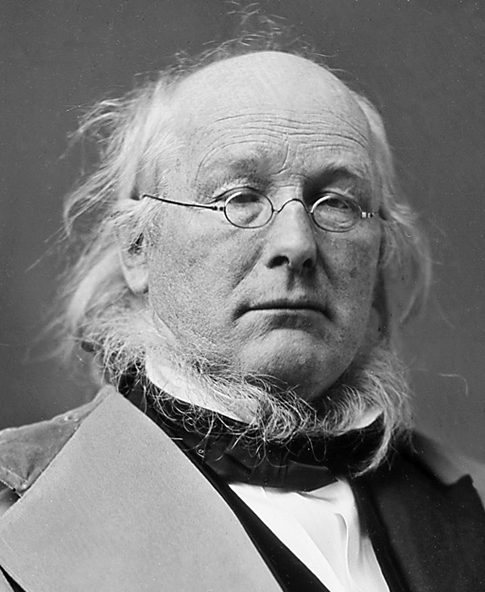

Thompson, whose influence with the Midwestern Know Nothings was considerable, assured them that Lincoln could not “be led into ultraism by radical men” and that his administration “will be national.” In choosing the Illinoisan over Seward, the delegates at Chicago “demonstrated to the country that the great body of the Republicans are conservative.” Lincoln’s “strength consists in his conservatism. His own principles are conservative.” Thompson asked Lincoln if it would be advisable to cite his 1849 vote against the Gott resolution in order to allay the fears of conservatives; the candidate hesitated to give permission, lest he alienate antislavery radicals. Lincoln replied: “If my record would hurt any, there is no hope that it will be over-looked; so that if friends can help any with it, they may as well do so. Of course, due caution and circumspection, will be used.” A week later, Horace Greeley pointed to Lincoln’s vote on the Gott resolution as proof of his conservatism.

"Lincoln and Know Nothings" p. 6

In July, when Thompson expressed a wish to meet with Lincoln, the candidate hesitated. Because Democratic papers had been accusing him of nativist proclivities (even alleging that he had attended a Know Nothing lodge), he wished to do nothing that might lend credence to those false charges. So rather than invite Thompson to Springfield, he dispatched Nicolay to Indiana with instructions to ask what his old friend wanted to discuss and to assure him that his motto was “Fairness to all,” but to make no commitments. In mid-July Nicolay carried out this mission, finding that Thompson “only sought to be assured of the general ‘fairness’ to all elements giving Mr Lincoln their support, and that he did not even hint at any exaction or promise as being necessary to secure the ‘Know Nothing’ vote for the Republican ticket.” Fearing the influence of Know Nothings in northern Illinois, Lincoln asked Thompson to write to John Wilson, an American party leader in Chicago who had been a delegate to the Constitutional Union party’s convention. Thompson complied, and Wilson abandoned the Bell movement after its Illinois leaders tried to merge with the Douglasites.