“Writing Lincoln’s Lives”

by Michael Burlingame

by Michael Burlingame

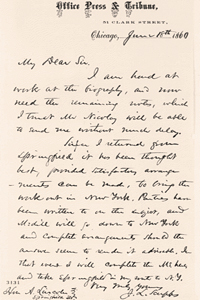

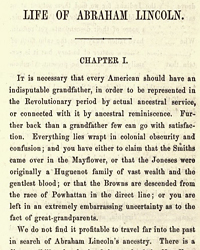

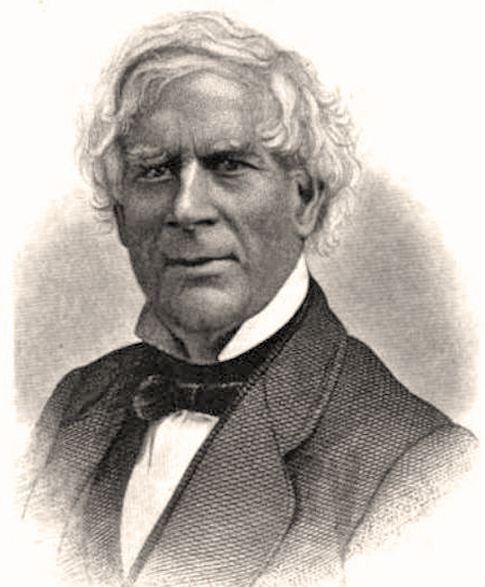

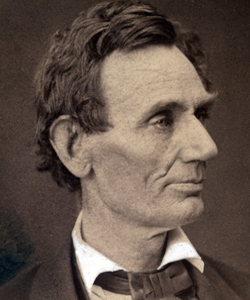

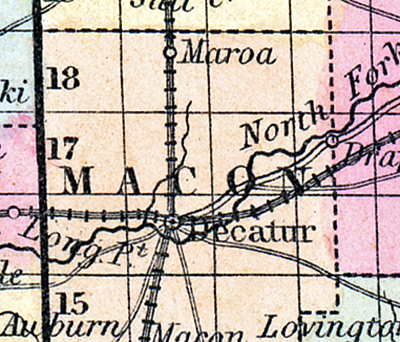

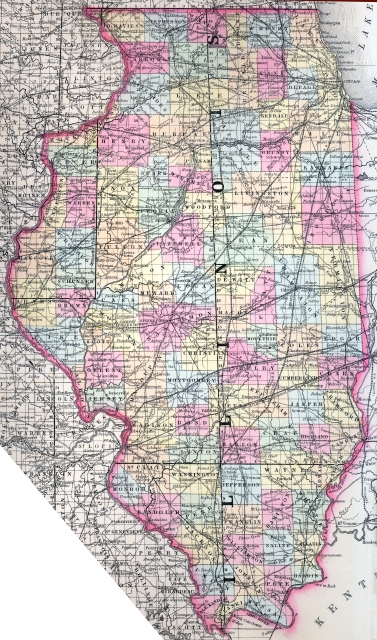

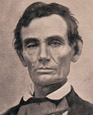

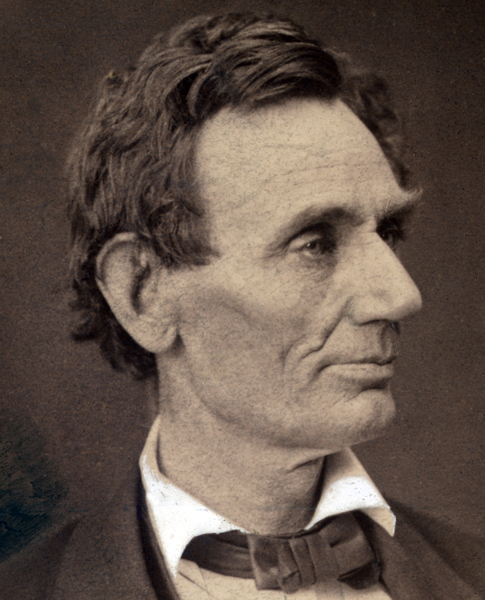

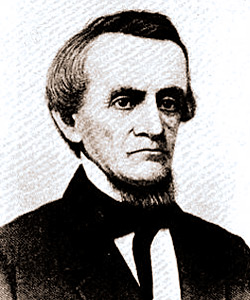

Publishers scrambled to meet the great demand for information about the little known Republican candidate, who at first was often referred to as Abram Lincoln. Thurlow Weed’s suggestion that Charles G. Halpine be given the task of writing a campaign biography came to nothing. The most informative of the thirteen campaign lives that did appear in 1860 were by William Dean Howells, a young Ohio journalist who was to achieve literary fame, and by John Locke Scripps, editor of the Chicago Press and Tribune and a good friend of Lincoln. For Howells, Scripps, and other authors, Lincoln prepared an autobiographical sketch which, though brief, was longer than the one he had drafted in 1859 for Jesse W. Fell. In this political document he said little about slavery, other than to reproduce his 1837 resolution denouncing the peculiar institution as based on “injustice and bad policy” and assert that his views had not changed since then. He devoted much more space to his Mexican War stand, correctly assuming that the Democrats would once again attack his record on that conflict.

“Writing Lincoln’s Lives” p. 2

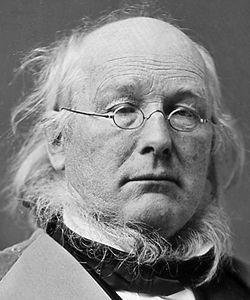

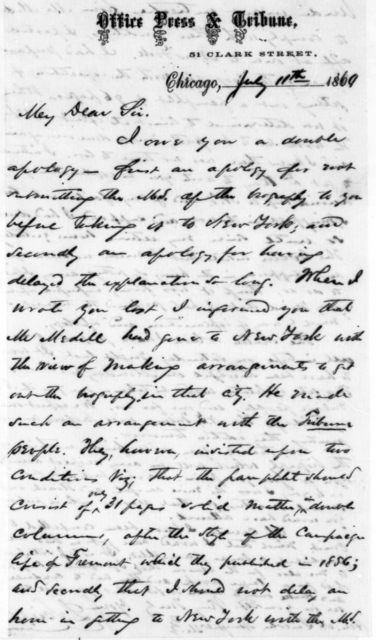

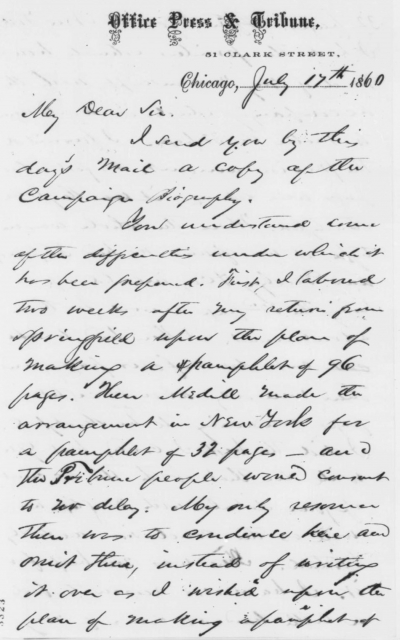

In addition to relying on that autobiographical sketch, Scripps sought to interview Lincoln about his life. At first the candidate was reluctant to cooperate, telling his would-be biographer: “it is a great piece of folly to attempt to make anything out of my early life. It can all be condensed into a single sentence and that sentence you will find in Gray’s Elegy: ‘The short and simple annals of the poor.’ That’s my life, and that’s all you or any one else can make of it.’” Nevertheless he told Scripps much about his life that was then incorporated into the campaign biography, making it virtually an autobiography. Hastily the busy editor churned out ninety-six pages of copy, only to be instructed by his New York publisher (Horace Greeley’s Tribune) to reduce it to thirty-two pages. After reluctantly making wholesale cuts, he apologized to Lincoln for the “sadly botched” final section, which was trimmed at the last minute. Amusingly he instructed the candidate that if he had not read Plutarch’s Lives, he should do so immediately, for the biography asserted that he had read it in his youth!

“Writing Lincoln’s Lives” p. 3

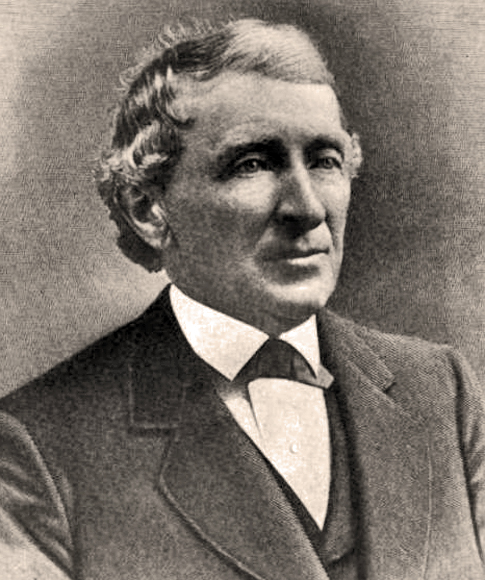

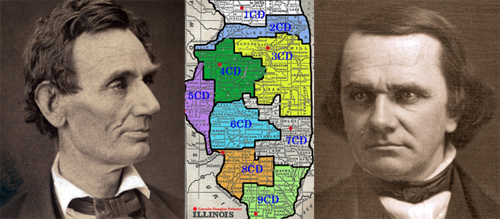

Earlier Scripps had written a 4000-word biographical sketch for the Chicago Press and Tribune which he used as the basis for his campaign life. That biography lacked a sentence that had appeared in his newspaper article: “A friend says that once, when in a towering rage in consequence of the efforts of certain parties to perpetrate a fraud on the State, he was heard to say ‘They shan’t do it, d—n ’em!’” Evidently it was thought advisable to play down Lincoln’s capacity for anger, which was formidable. Like Scripps’s biography, William Dean Howells’s was enriched by interviews. They were conducted by a research assistant, James Quay Howard, who visited Springfield and talked briefly with Lincoln and at greater length with several of his friends. When the publisher, Follett and Foster of Columbus Ohio (who had issued the Lincoln-Douglas debates earlier that year) advertised it as an “authorized by Mr. Lincoln,” the candidate protested vigorously. To Samuel Galloway he complained about Follett and Foster: “I have scarcely been so much astounded by anything, as by their public announcement that it is authorized by me.” He had, he said, made himself “tiresome, if not hoarse, with repeating to Mr. Howard” that he “authorized nothing – would be responsible for nothing.”

“Writing Lincoln’s Lives” p. 4

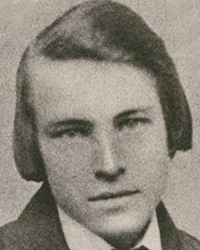

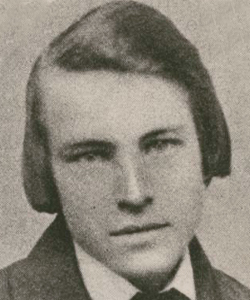

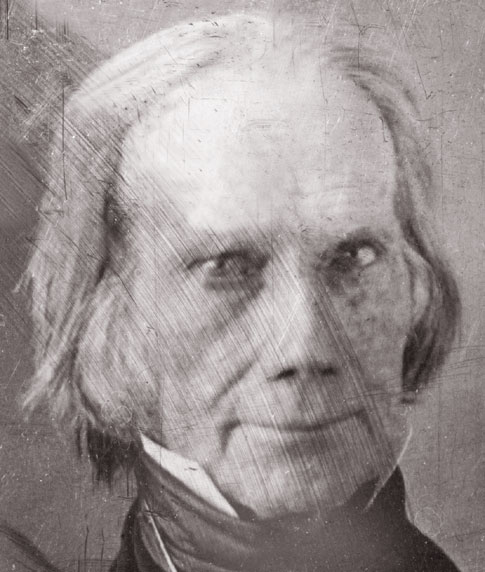

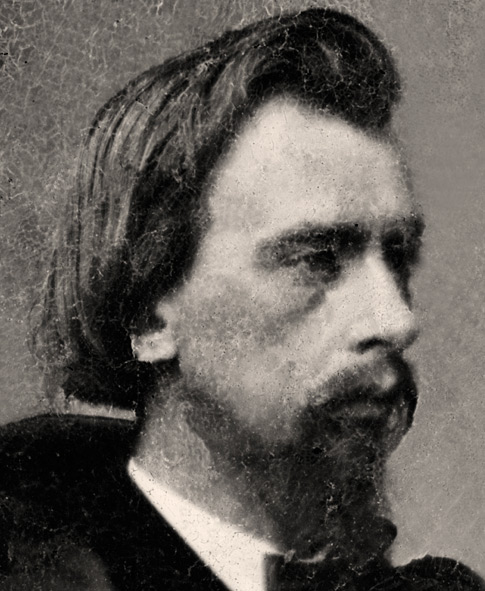

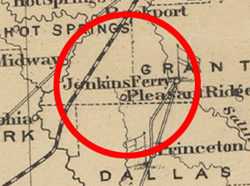

[Lincoln] would not endorse a biography unless he thoroughly reviewed and corrected it, which he was then unable to do. He could not obey the advice of all his “discreet friends” to make no public statements while simultaneously approving a campaign life for his opponents “to make points on without end.” If he were to do so, “the convention would have a right to reassemble” and name another candidate. To maintain deniability, Lincoln refused to read the manuscript of any campaign biography. He had his friends at the Illinois State Journal run a disclaimer and his secretary write letters of protest both to Howard and to Follett and Foster. That secretary was the industrious, efficient John G. Nicolay, a twenty-eight-yearold, German-born journalist from Pike County who since 1857 had been clerking for secretary of state Ozias M. Hatch. A week before the Chicago Convention he had helped build support for Lincoln’s candidacy in an elaborate article comparing his record on slavery with Henry Clay’s, arguing that they were very similar. He probably did so at the suggestion of the would-be candidate, who may have written the piece.

“Writing Lincoln’s Lives” p. 5

Since 1858, Nicolay had been writing occasional articles for the Missouri Democrat of St. Louis; he filed a long report on the Chicago Convention for that newspaper. Shortly after that conclave, Lincoln told Hatch: “I wish I could find some young man to help me with my correspondence. It is getting so heavy I can’t handle it. I can’t afford to pay much, but the practice is worth something.” When Hatch recommended Nicolay, Lincoln found it easy to accept the advice, for he regarded the young man as “entirely trust-worthy” and had often conversed and played chess with him in Hatch’s office, which served as an informal Republican headquarters. Nicolay had hoped to be given the task of writing a campaign biography and was “filled with jealous rage” when Howells was chosen. He was solaced when Lincoln hired him at $75 per month, for he vastly admired his employer, who served as a kind of surrogate father to the orphaned Nicolay.

Life of Abraham Lincoln (1860)

Sidenotes

| Events | Places |

| Major Topics | Sources |

| People |