Home > People

- Profile

- Documents

- Images

- Timeline

- Data

- Sources

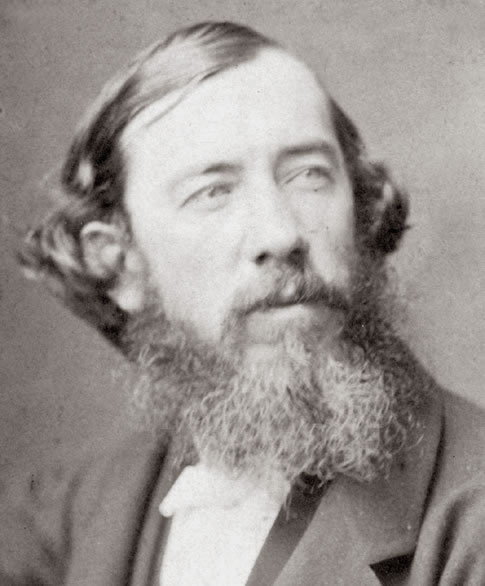

Moncure Daniel Conway

Moncure Daniel Conway was born the second son of and old and distinguished Virginia family on March 17, 1832 in Stafford County, Virginia. He was related to the Washingtons, the Madisons, and the Lees. His uncle on his mother’s side sat as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. Both his father, Walker Peyton Conway, a prominent slaveholding landowner and his mother, Margaret Daniel Conway, had converted after their marriage to Methodism and the Conway children were exposed at an early age to disciplined evangelicalism. Moncure Conway first was schooled at home then attended the thriving Fredericksburg Classical and Mathematical Academy, a school that had educated Washington and other famous Virginians. He then followed his brother Peyton to Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania as a fifteen-year-old sophomore. The Methodist affiliated institution cemented his faith and he fell somewhat under the influence of professors George Crooks and John McClintock. He did not share the latter’s fierce abolitionism and almost left the college when McClintock was involved in a notorious riot in the town that freed recaptured slaves and resulted in the death of a slave catcher. He graduated with the class of 1849 and returned home to Virginia to study law with a family friend in Warrenton.

Though his family connections alone guaranteed a bright legal future, the young Conway was an indifferent law student. Despite the urging of his numerous cousins to take up his place as an active defender of the South, he was already having significant problems justifying his beloved Virginia’s maintenance of slavery. Despite this, he served in 1850 as the secretary of the Southern Rights Association in Warrenton, and seemed in his momentary embracing of the recently published racial theories of Louis Agassiz to be searching for any justification for human bondage. Despairing of the law, he pleased his parents at last when on his nineteenth birthday he became a Methodist circuit rider preacher, assigned to the Rockville, Maryland area. During the next three years he rode northern Maryland, literally expanding contacts with the world, which included an influential friendship with a family of Quakers. Most importantly he indulged in the obsessive reading that was to adjust both his ideas about religion and slavery. Under the influence of writers such Ralph Waldo Emerson, he left the Methodist circuit in February, 1853, went north to Boston and enrolled in the Unitarian dominated Harvard Divinity School. While there he met and befriended Emerson and Thoreau and settled his mind against slavery. He was still a southerner, however, and became involved in the famous case of Anthony Burns, a recaptured slave being returned from Boston to Virginia under the new and hated federal Fugitive Slave Law. He refused publicly to rally in support of the action with other southern students but also declined in private to aid abolitionist friends in accosting Burn’s Virginia slave owner --- whom he knew slightly from earlier days in Fredericksburg --- thereby offending both sides.

He graduated from Harvard Divinity and took up a post as minister of the First Unitarian Church of Washington D.C. in late October 1854. All his time in the capital did, however, was to convince him that war over the sectional question was inevitable. In January 1856, he gave his solution for the avoidance of such a violent outcome. He preached from his pulpit the minority opinion that disunion was preferable to civil war and that an independent South would be left to work out emancipation through the moral example of the free labor North. This pleased few members of his congregation on either side of the question and as the sermon gained in national notoriety he was dismissed the following October. He was soon in the pulpit again, however, this time in Cincinnati, Ohio. A far more liberal membership welcomed him and his anti-slavery work there and he continued his development in both study and writing. He also met and married Ellen Dana in June 1856, beginning a sustaining and enduring partnership that was to last almost forty years.

In 1860 Moncure Conway, in the only presidential election in which he ever voted, cast his ballot for Abraham Lincoln. Soon his greatest fears were realized with the outbreak of the Civil War. The state he loved was invaded and his family split. His two younger brothers served in the Confederate Army while he and a sister remained in the North. He did return to the South for a few days in the late summer of 1862 to find and gather his father’s slaves who had fled from Virginia to Washington when Union troops had overrun the Conway plantation. Finding them in hiding in the capital, he transported them through a series of ruses, including playing the slave owner by marching them through pro-slavery Baltimore with a whip to the railway station, to freedom in Ohio.

He declined an offer to serve as a chaplain in the Union Army but accepted a mission on behalf of Wendell Phillips and other abolitionists to explain anti-slavery and the Union cause to a divided Britain. He traveled to London in April 1863 and was well received in intellectual circles. He soon caused a storm, however, when his personal enthusiasm overwhelmed his limited skills as a diplomat when he precipitously offered the Confederate representative in Britain the full opposition of northern abolitionists to any further prosecution of the war in exchange for the immediate emancipation of all slaves held in the Confederate states. Mason rebuffed him publicly in a letter to The Times of London on July 10, 1863, and American abolitionism instantly disowned him. He was forced to explain himself to the United States ambassador, Charles Francis Adams, and apologize for any appearance of treason in his remarks. Humiliated and feeling cut off from his home, he took up a post at the South Place Chapel in London and did not return to the United States.

The South Place Chapel was at the center of a group that had been founded in the early years of the century on the ideals of personal virtue that superceded faith or doctrine and Conway’s new post gave him the chance to bloom as a free thinker. He stayed at South Place for seventeen years, traveling, lecturing, and publishing many of the memorable works that were going to rehabilitate his reputation. He returned home in 1884 at the death of his father but returned to South Place in 1892. In 1897, he was forced to return home again when his wife fell ill. She died on Christmas Day in New York. The couple had raised three children.

With the loss of his dear companion and continued disillusion with what he saw as imperial United States policy, he left home once again to live the rest of his life in London and Paris. He visited to lecture occasionally and remained in touch with his alma mater where, in the year of Conway’s death, his friend and fellow advocate for world peace Andrew Carnegie donated funds to build a hall to bear his name.

Moncure Conway died alone amidst his books and writings in his Paris apartment on November 15, 1907. He was seventy-five years old.

“Letters from Friends of the Cause,” Liberator, Boston, 18 February 1859, p. 27.

National Anti-Slavery Standard, 15 May 1858.

M. D. Conway, “Selections,” Liberator, Boston, 22 February 1856.

“Speech of Rev. Mr. Conway,” Liberator, Boston, 6 June 1856.

Liberator, Boston, 21 November 1856, p. 187.

“An Ancient and A Modern Compromise,” Liberator, Boston, 19 April 1861, p. 0_1.

"Speech of Rev. M.D. Conway,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, 9 August 1862, p. [Not

Listed].

G. W. S., “The Two Capitals,” Liberator, Boston, 28 November 1862, p. 190.

“Mr. Conway’s Lecture,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, 8 February 1862, p. [not listed]

“New Publications,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, 19 July 1862, p. #.

"A Practical Joke," Charlestown Mercury, April 13, 1949, p. 2.y

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, January 1, 1852.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, March 17, 1852.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, March 26, 1852.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 20, 1852.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, June 28, 1852.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, July 1, 1852.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, September 19, 1852.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, September 20, 1852.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, September 21, 1852.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, September 22, 1852.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, September 23, 1852.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, October 14, 1852.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, December 25, 1852.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, January 1, 1853.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, March 17, 1853

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, May 3, 1853

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, June 27, 1853

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, January 1, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, June 28, 1853.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, January 11, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, June 29, 1853.

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, January 18, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, January 20, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 1, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 2, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 3, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 4, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 5, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 6, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 7, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 8, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 9, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 10, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 11, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 12, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 13, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 14, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 15, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 16, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 17, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 18, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 19, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 20, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 21, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 22, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 23, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 24, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 25, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 26, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 28, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 29, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, April 30, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, May 1, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, October 1, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, October 2, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, October 3, 1851

Moncure Daniel Conway Journal, December 28, 1851

Dickinson College holds annual commencement ceremonies

Image Gallery

| March 17, 1832 | Born in Stafford County, Virginia |

| 1849 | Graduated from Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania |

| February 1853 | Leaves Methodist circuit for a new life in New England |

| October 1854 | Becomes Unitarian minister in Washington, D.C. |

| June 1856 | Marries Ellen Dana |

| Summer 1862 | Helps father’s slaves relocate to Ohio during Civil War |

| April 1863 | Leaves the United States for England |

| November 15, 1907 | Dies in Paris |

| Race: | White |

| Gender: | Male |

| Birthplace: | Slave State |

| Slaveholder: | No |

| Education: | Dickinson College / Harvard Divinity School |

| Profession: | Minister |

| Religion: | Unitarian |

| Political Party: | Republican |

Selected Bibliography

Books:

Burtis, Mary Elizabeth. Moncure Conway, 1832-1907. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1970.

D'Entremont, John. Southern Emancipator: Moncure Conway, The American Years, 1832-1865. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Emerson, Edward D. Moncure D. Conway. Boston: 1908.

Mansford, Wallis. Dr. Moncure D. Conway. Westminster: 1937.

Articles:

Boorstein, Michelle. "From 1850s Virginia, an Abolitionist Hero Emerges.” The Washington Post, 22 August 2004.

“Conway Family.” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 12, no. 4 (April 1904): 264-267.

Earle, Jonathan. “The Making of the North's ‘Stark Mad Abolitionists’: Anti-Slavery Conversion in the United States, 1824-54.” Slavery & Abolition [Great Britain] 25, no. 3 (2004): 59-75.

Smith, Warren Sylvester. “ ‘The Imperceptible Arrows of Quakerism’: Moncure Conway at Sandy Spring.” Quaker History 52, no. 1 (1963): 19-26.

Primary Sources:

Conway, Moncure Daniel. Autobiography, Memories and Experiences of Moncure Daniel Conway. New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1904.

Conway, Moncure Daniel. Moncure D. Conway; Addresses and Reprints, 1850-1907. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1909.

Conway, Moncure D. “Abolitionism and Southern Independence.” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 25, no. 2 (October 1916): 137-138.

Conway, Moncure Daniel. Moncure Conway Letters. Washington, DC: Library of Congress Photoduplication Service, 1971.