John Weigel, “‘Americans Shall Rule America!’ The Know-Nothing Party in Cumberland County,” Cumberland County History 15 (1998): 3-18.

John Weigel, “Free Soil: The Birth of the Republican Party in Cumberland County,” Cumberland County History 17 (2000): 36-57.

John Weigel, “In Defense of Union and White Supremacy: The Democratic Alternative to Free Soil, 1847 – 1860,” Cumberland County History 17 (2000): 103-117.

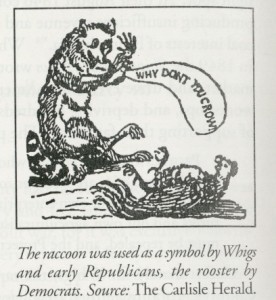

In a series of three essays John Wesley Weigel traces the political history of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania between the late 1840s and the Republican victory in the Presidential election of 1860. Weigel’s articles are based in large part on primary sources, in particular three local newspapers: Carlisle (PA) Herald , Carlisle (PA) American Volunteer, and the Shippensburg (PA) News. All three articles include extensive endnotes. Weigel’s essay of the rise of the Republican party in Cumberland county includes two maps and a graph related to voter turnout. In addition, Weigel provides two detailed charts that breakdown Cumberland county votes by party between 1839 and 1873.

This essay has been posted online with permission from the Cumberland County Historical Society.