The Soldiers Aid Society of Carlisle, Pennsylvania  formed on August 25, 1863 and disbanded sometime in 1865. The organization provided the thousands of men who enlisted in the Union Army with blankets ,clothing ,as well as local fruits produce. Women were the driving force and chose to spearhead these efforts because they felt they had a better knowledge of what would comfort the soldiers and the domestic skills to enable their work to be successful. In addition, the Soldiers Aid Society assisted with burials and grave decoration for the soldiers that died in battle.

formed on August 25, 1863 and disbanded sometime in 1865. The organization provided the thousands of men who enlisted in the Union Army with blankets ,clothing ,as well as local fruits produce. Women were the driving force and chose to spearhead these efforts because they felt they had a better knowledge of what would comfort the soldiers and the domestic skills to enable their work to be successful. In addition, the Soldiers Aid Society assisted with burials and grave decoration for the soldiers that died in battle.

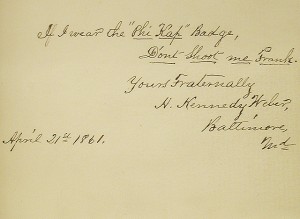

The women and men of the Soldiers Aid Society provided a welcoming place for the soldiers before and after they left for battle by exchanging tokens of affection with the soldiers such as handkerchiefs explained by James W. Sullivan in Boyhood Memories: ” The women of Carlisle had brought out from their scantily stocked larders the essentials of a welcoming reception.” The Carlisle American also describes the women’s actions “by expressing tokens of love but cheerfulness” ( Carlisle American. 25 April 1863. Back at Home section).

The church dynamic was vital to the success of the society because many of the members belonged to the First Presbyterian Church of Carlisle and as a result attracted other religious organizations of the community and surrounding areas. The Soldier Aid Society of Carlisle worked with many Sanitary Commissions and ” resoleved a draft for a systematci plan for securing contrubutions in the town”, according to the American Volunteer (American Volunteer, Central Fair in Aid and the Sanitray Commission. Back at Home section).

The organization also involved many social classes of people. The society allowed the whole community to have a common goal no matter if you were an educated man or a domestic homemaker. Motivations varied from patriotic or Christian duty to personal reasons, but they all brought people together in unity to aid in the war effort and provide solace to each other while loved ones were in harms way.

Many Soldiers Aid Societies existed at the time that were similar to that of the one in Carlisle. The United States Sanitary Commission of the Cleveland Branch provides the first annual report of the Soldiers Aid Society of Cleveland, the area where the first soldiers aid societies began. Google Books provides a preview of Civil War Sisterhood: The U.S. Sanitary Commission and Women’s Politics in Transition which discusses the relationship between Sanitary Commisions and Solders Aid Societies during the Civil War.

Huntington Friends Meeting

Huntington Friends Meeting