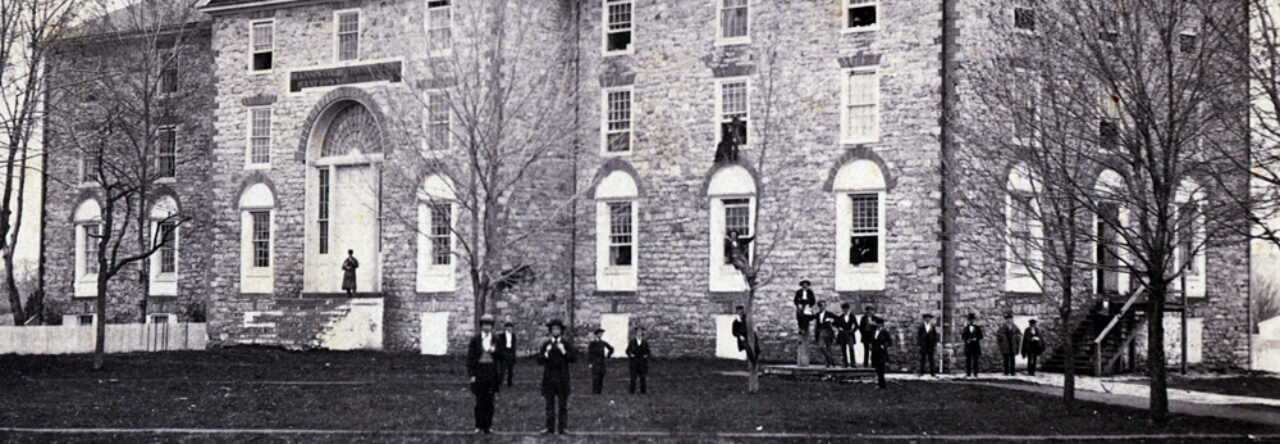

Charles Albright and George Baylor both spent their formative years as students at Dickinson College, and their shared participation in the Union Philosophical Society helped define their experience on campus. Despite their immediate similarities on campus, Baylor enrolled in Dickinson six years after Albright left campus in pursuit of a profession in law. Baylor’s wealthy roots in Jefferson County, Virginia, his birthplace, only accentuated his stark differences with Albright, who grew up in Berks County, Pennsylvania. Albright also demonstrated his fervent opposition to slavery in the decade prior to the outbreak of war, a sentiment not shared by Baylor, who immediately joined the Confederate army in May 1861. Both Baylor and Albright enlisted in the military and went on to become respected leaders in their respective units. Their dedicated service brought the otherwise unlikely pair of Dickinson students together in April 1865 in northern Virginia.

Charles Albright and George Baylor both spent their formative years as students at Dickinson College, and their shared participation in the Union Philosophical Society helped define their experience on campus. Despite their immediate similarities on campus, Baylor enrolled in Dickinson six years after Albright left campus in pursuit of a profession in law. Baylor’s wealthy roots in Jefferson County, Virginia, his birthplace, only accentuated his stark differences with Albright, who grew up in Berks County, Pennsylvania. Albright also demonstrated his fervent opposition to slavery in the decade prior to the outbreak of war, a sentiment not shared by Baylor, who immediately joined the Confederate army in May 1861. Both Baylor and Albright enlisted in the military and went on to become respected leaders in their respective units. Their dedicated service brought the otherwise unlikely pair of Dickinson students together in April 1865 in northern Virginia.

After graduating with the Class of 1860, Baylor returned to the academy he attended in Virginia as a child to teach. He kept this position until May 1861 when he enlisted in the Confederate army as a private. By 1863, Baylor established his reputation as an indefatigable and effective cavalry leader. His successful raids through Virginia in 1863 and 1864 only strengthened this reputation from the perspective of Colonel J. S. Mosby, who ensured the appointment of Baylor as captain of the company formed in April 1865. Less than a week after its formation, the unit encountered Union troops near Fairfax Station, Virginia and Baylor reluctantly retreated. He did not know, however, that the colonel leading the Union force was Charles Albright, fellow Dickinson alumnus and member of the Union Philosophical Society.

Well before confronting Baylor’s soldiers in 1865, Albright first established his military record in the Union army as a volunteer in a company dedicated to the protection Washington, D.C. He spent much of his service in Pennsylvania, first as a leader in the Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry and then as the commanding officer of Camp Muhlenberg in Reading. In September 1864, after having moved throughout the state with the Volunteer Infantry, Albright led the Infantry’s 202nd Regiment against several raids conducted by Confederate soldiers in attempts to sabotage Virginia’s railways. Albright attempted to stop one such raid, planned by Baylor, on April 10, 1865.

Albright’s report of the raid and his unit’s victory over Baylor’s soldiers noted that those Confederate soldiers who were not killed or did not escape were taken prisoner. In a less formal account of the attack, Albright told his superior that he “whipped him like thunder.” As one would expect, Baylor’s memoirs detail the events in a much different manner. Of the battle Baylor said that “if the critic will carefully review the reports from the Colonel himself, the advantage will appear exceedingly small” and, responding directly to Albright’s description of the confrontation, “I hope the devil will never whip him any worse.” This chance meeting between Dickinson alumni, however separated by class, background, politics, or ideology, illustrated one way the war divided a single campus. Student populations at Dickinson divided fairly evenly between Union and Confederate allegiances. While the campus saw the early manifestations of these divisions among students, some class members saw it demonstrated on the battlefield.

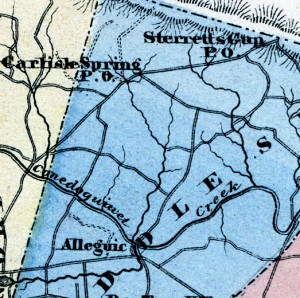

The Shelling of Carlisle Map

The Shelling of Carlisle Map