On the evening of June 28, 1863, Confederate General John B. Gordon reached his objective in Columbia, Lancaster County: the one and one quarter mile covered bridge of Columbia-Wrightsville. As the Rebels charged onto the first span of the bridge, four explosions went off, stopping them from charging the bridge. Union Colonel Jacob C. Frick and his soldiers received orders to protect the bridge by Union General Darius N. Crouch, but the Rebels persisted. The local militia began to blow up several spans of the bridge to prevent the Rebels from crossing. This ended up failing, so as a last resort a fire was set to destroy the entire span of the bridge. Due to the windy night, the fires spread to parts of Wrightsville, burning farms and homes. In the end, Frick saved the town by stopping the Confederates, but lost the bridge he was to protect. Frick discusses his feelings on his orders from Couch:

“My duty in the premises was plain. Gen. Couch plainly indicated my duty in his orders, wherein he said: “When you find it necessary to withdraw your command from Wrightsville leave a proper number on the other side to destroy the bridge; keep it open as long as possible with prudence and exercise your own discretion in doing so.”

Google Books provide resources such as Donald Jackson’s Great American Bridges and Dams, giving a brief history of the bridge before the burning in 1863. The United States of American Congressional Record also has an article with a small summary on the burning of the bridge and the history of the bridge’s structure.

Location – Columbia and Wrightsville, PA

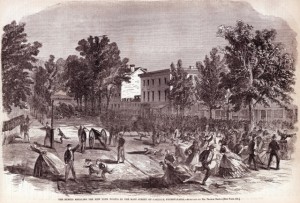

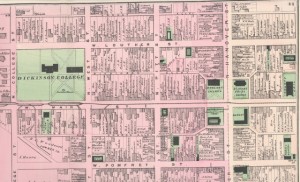

The Shelling of Carlisle Map

The Shelling of Carlisle Map

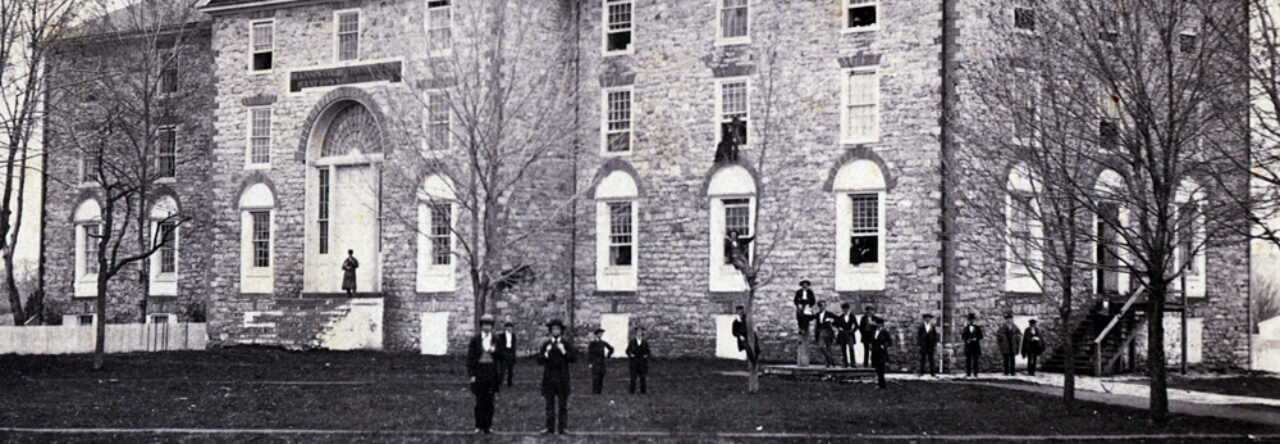

Huntington Friends Meeting

Huntington Friends Meeting