Sources

Important primary sources on Brown’s Harpers Ferry raid include James Redpath’s The Public Life of Capt. John Brown (1860), Franklin B. Sanborn’s The Life and Letters of John Brown, Liberator of Kansas, and Martyr of Virginia (1885), and Richard J. Hinton’s John Brown and His Men; With Some Account of the Roads Traveled to Reach Harper’s Ferry (1894). Osborne Anderson, who participated in Brown’s raid but managed to escape, also published his account in 1861: A Voice from Harper’s Ferry: A Narrative of Events at Harper’s Ferry. Important secondary sources include Benjamin Quarles’ Allies for Freedom; Blacks and John Brown (1974), Paul Finkelman’s His Soul Goes Marching On: Responses to John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid (1995), David S. Reynolds’ John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (2005), and Jonathan Earle’s John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry: A Brief History with Documents (2008).

Places to Visit

You can visit Harpers Ferry National Historical Park in West Virginia and see John Brown’s fort and the historic town. In addition, the Kennedy Farmhouse is only about 30 minutes from Harpers Ferry. The farmhouse, which became a National Historic Landmark in 1973, is the place where Brown’s raiders launched their attack on Harpers Ferry.

Artifacts

A number of institutions have one of Brown’s pikes in their collection, including the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, the Jefferson County Historical Society in West Virginia, and the National Museum of American History. In addition, the National Museum of American History has “John Brown’s Sharps Rifle” and another rifle seized during the attack on Harpers Ferry.

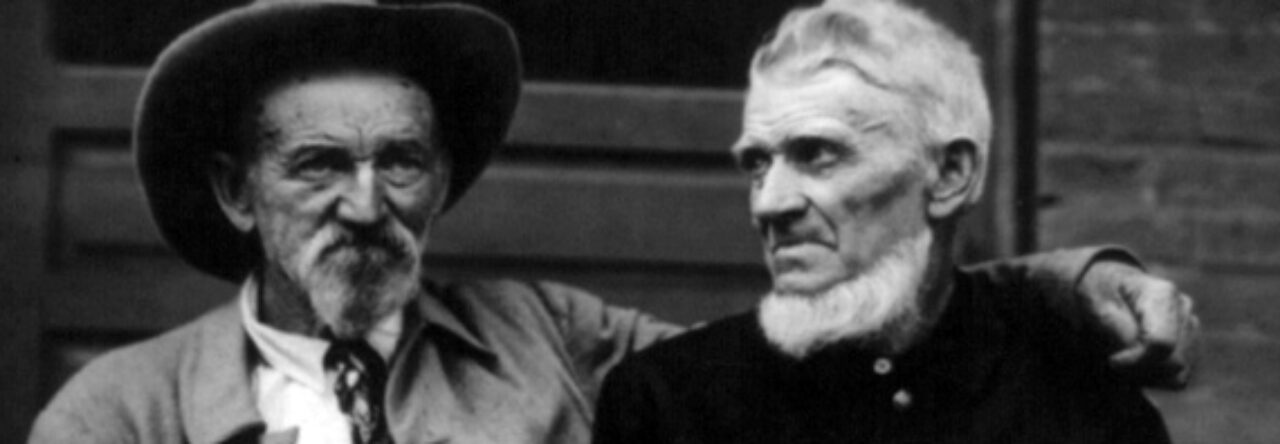

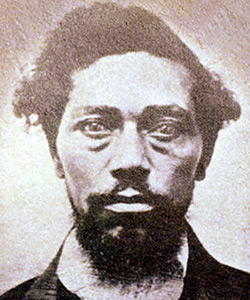

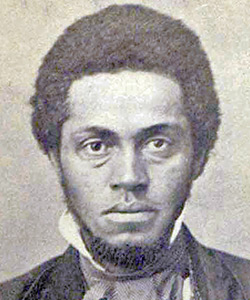

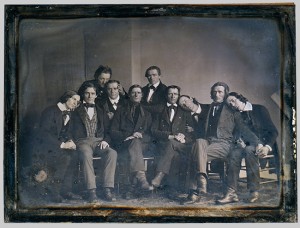

Images

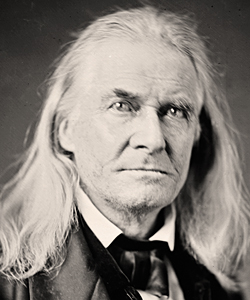

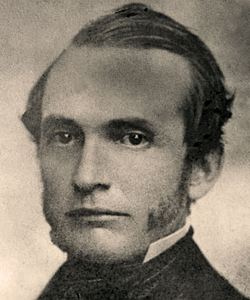

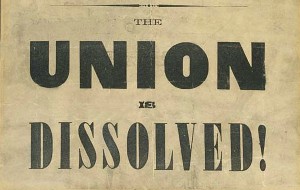

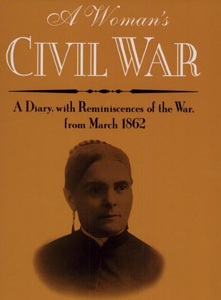

The slideshow below includes images related to Brown’s attack on Harpers Ferry in October 1859.